Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Are Sleep-Related Eating Disorders?

- Type #1: Sleep-Related Eating Disorder (SRED)

- Type #2: Night Eating Syndrome (NES)

- Other Nighttime Eating Patterns People Confuse With “Sleep Eating”

- Signs and Symptoms

- What Causes Sleep-Related Eating Problems?

- How Doctors Diagnose It

- Treatments That Actually Help

- How to Help During an Episode (Without Making It Worse)

- When to Seek Professional Help

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Experiences: What Living With Sleep-Related Eating Issues Can Feel Like (and What Helps)

- Conclusion

- SEO Tags

If you’ve ever found a mysterious smear of peanut butter on the counter and thought, “Huh. Ghosts?”

you’re not alone. Sometimes the culprit isn’t paranormalit’s your brain doing a very weird

“autopilot snack run” while you’re asleep.

Sleep-related eating problems can range from “I wake up and choose cereal” to “I’m technically asleep and

apparently tried to cook.” The difference mattersbecause the causes, risks, and treatments aren’t the same.

Let’s break down the main types, what’s actually going on in the body, how clinicians diagnose it, and what

treatments tend to help (without turning your kitchen into Fort Knox… unless your doctor says that’s a good idea).

What Are Sleep-Related Eating Disorders?

“Sleep-related eating disorders” is an umbrella term people use to describe recurring patterns of eating at night

that are linked to sleep. Clinically, two conditions come up most often:

-

Sleep-Related Eating Disorder (SRED): Episodes of eating during partial arousals from sleep,

often with little or no memory afterward. This is considered a parasomnia (a disorder of unwanted

behaviors during sleeplike sleepwalking). -

Night Eating Syndrome (NES): A pattern of eating a large portion of daily calories in the evening

and/or waking to eat, typically with awareness and recall. This is more aligned with an eating/circadian

pattern plus insomnia symptoms, not a sleepwalking-type event.

The tricky part: both can look like “night eating,” but the “how” is different. In SRED, the brain is partly asleep.

In NES, the person is awake enough to remember and often reports feeling they “need” to eat to fall back asleep.

Type #1: Sleep-Related Eating Disorder (SRED)

What it looks like

In SRED, a person may get out of bed and eatsometimes quickly, sometimes oddlyduring a partially awake state.

In the morning, they may have partial or complete amnesia for the episode. Some people discover

evidence (wrappers, messes, missing food) rather than memories.

Common clues that point toward SRED

- Eating happens after an arousal from sleep (often in the first part of the night, but not always).

- Confused, “glassy-eyed,” hard-to-fully-wake behavior during an episode.

- Little to no recall the next day.

- Other parasomnias may be present (sleepwalking, confusional arousals).

- Episodes may be linked to certain medications or other sleep disorders.

Why it happens (the short, non-spooky version)

SRED is generally understood as a non-REM parasomniameaning the brain is stuck between sleep and wake.

Think of it like a computer that’s half-updated: the “movement” program runs, but the “full awareness” program doesn’t.

Many cases occur alongside (or are triggered by) things that increase arousals from sleep, such as:

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): repeated breathing disruptions can fragment sleep.

- Restless legs syndrome (RLS) / periodic limb movements: can also break sleep continuity.

- Narcolepsy or other sleep disorders that destabilize sleep architecture.

- Stress, sleep deprivation, irregular schedules.

-

Medicationsespecially certain prescription insomnia drugs associated with “complex sleep behaviors”

(sleepwalking, sleep cooking, sleep eating).

Why it can be risky

Beyond the obvious “Why is there ketchup in my sock drawer?” factor, SRED can be dangerous because the person may:

- Use knives or appliances while not fully awake.

- Eat raw/unsafe foods or even non-food items by mistake.

- Experience disrupted sleep, daytime fatigue, or mood effects.

- Develop health complications over time (not because of “willpower,” but because sleep is being disrupted and eating is dysregulated).

Type #2: Night Eating Syndrome (NES)

What it looks like

Night Eating Syndrome typically involves a pattern like:

reduced appetite in the morning, increased intake in the evening, and/or waking to eat at night.

Unlike SRED, many people with NES are aware of the eating and remember it. Insomnia symptoms are common, and some people

report feeling they need to eat to fall back asleep.

NES vs. “I just snack at night sometimes”

Occasional night snacking is common and not automatically a disorder. NES is more about a consistent pattern that causes

distress or impairment. Clinicians look for repeated, meaningful symptomsoften several times per weekplus a sense that the

pattern is hard to stop and is tied to sleep disruption or circadian rhythm shifts.

Why it happens

NES is thought to involve a mix of circadian rhythm factors, sleep disruption (especially insomnia),

and psychological components (stress, mood symptoms). The body’s “timing signals” for hunger and sleep can drift out of sync.

Other Nighttime Eating Patterns People Confuse With “Sleep Eating”

Intentional late-night eating

Some people eat late because of work schedules, training, or culturetotally different situation. If you’re awake, aware,

and choosing food, that’s not SRED.

Binge eating episodes at night

Binge eating can happen any time of day, including evenings. The key difference is awareness and recall.

If a person is awake and distressed by loss of control, that points away from SRED and toward an eating-disorder evaluation.

Medication-related “complex sleep behaviors”

Some prescription insomnia medications have been associated with rare but serious complex sleep behaviors (including sleepwalking

and sleep eating). If nighttime eating started after a new sleep medicationor changed dosethis is a major “tell your prescriber”

moment, not a “shrug and hide the cookies” moment.

Signs and Symptoms

Possible signs of SRED

- Evidence of eating with little/no memory afterward (missing food, wrappers, messes).

- Unusual food combinations or eating items you wouldn’t normally choose.

- Episodes of wandering similar to sleepwalking.

- Injuries or near-misses in the kitchen without clear recall of how they happened.

- Daytime sleepiness from fragmented sleep.

Possible signs of NES

- Eating a large portion of daily intake after dinner or late at night.

- Waking to eat and remembering the episode.

- Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep (insomnia).

- Morning lack of appetite.

- Distress or shame about the pattern (which, importantly, can make sleep worse).

What Causes Sleep-Related Eating Problems?

There usually isn’t one single cause. Instead, think in categories:

1) Sleep fragmentation

Anything that repeatedly bumps the brain toward wakefulnesslike sleep apnea or periodic limb movementscan set the stage for

parasomnias, including SRED.

2) Medications and substances

Certain medications can increase the odds of complex sleep behaviors in susceptible people. If you suspect this, do not

self-adjust prescriptionscontact the prescriber promptly so they can advise a safe plan.

3) Stress, irregular schedules, and sleep deprivation

When sleep is short or chaotic, the boundary between sleep and wake can get “leaky,” and parasomnias become more likely.

Your brain is basically running on low battery and making questionable decisionslike thinking the fridge is a great idea at 2 a.m.

4) Mood and anxiety factors (especially in NES)

In NES, insomnia, stress, and mood symptoms can reinforce the pattern: poor sleep increases late-night wakefulness, which increases

opportunities to eat, which can then increase stress, which further disrupts sleep. It’s a loopnot a moral failing.

How Doctors Diagnose It

Diagnosis is mostly about a careful history. Because SRED often includes amnesia, clinicians commonly ask for input from a bed partner,

roommate, or family membersomeone who can describe what happens during the night.

What an evaluation may include

- Symptom timeline: When did it start? How often? Any triggers?

- Medication review: Especially sleep aids, psychiatric medications, and anything that affects the nervous system.

- Sleep history: Snoring, gasping, restless legs sensations, daytime sleepiness, irregular schedule.

- Sleep diary: Bedtime, awakenings, eating episodes, alcohol/caffeine timing, stress levels.

-

Polysomnography (sleep study): Sometimes used when clinicians suspect sleep apnea, periodic limb movements,

or another sleep disorder that could trigger arousalsespecially if episodes are frequent or risky.

Getting the “right label” matters because SRED is generally treated as a parasomnia (often by addressing sleep disorders or medications),

while NES often responds to a combined approach targeting insomnia/circadian timing and eating-disorder psychology.

Treatments That Actually Help

The best treatment plan depends on the type and the “why.” But most evidence-based strategies fall into a few practical buckets:

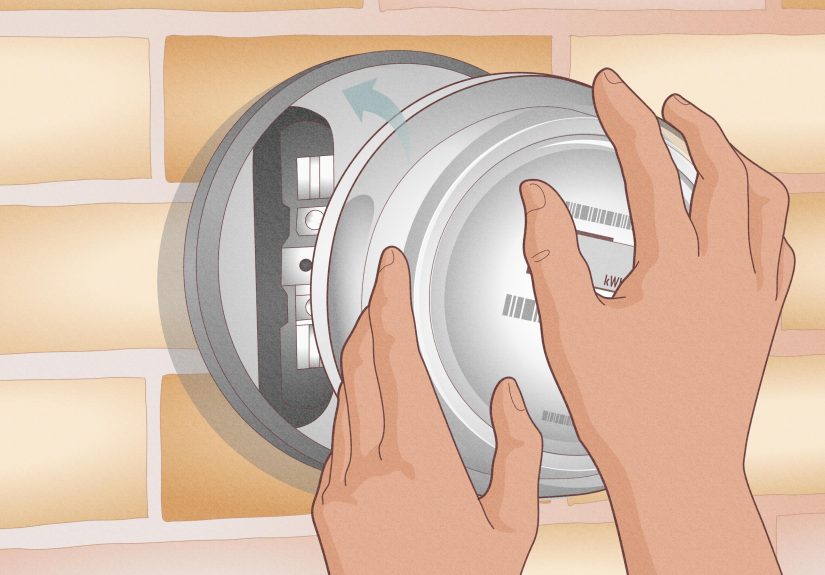

1) Make the environment safer (especially for SRED)

Because SRED can involve cooking or using sharp objects while not fully awake, safety is a first priority. Common clinician suggestions include:

- Keep dangerous items (knives, glass, cleaning chemicals) secured or out of easy reach at night.

- Unplug or disable small appliances overnight if episodes are frequent.

- Consider stove/oven safety knobs or device locks if there’s a history of nighttime cooking.

- Use door alarms or motion lights as gentle alerts for caregivers/partners (not as “punishment”).

The goal is not to “trap” someoneit’s to reduce the chance of accidents during an episode.

2) Treat underlying sleep disorders

If sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, or periodic limb movements are part of the picture, treating those can reduce sleep fragmentation

and, in turn, reduce parasomnia episodes. This might involve CPAP for sleep apnea, iron evaluation for RLS, or other clinician-directed therapies.

3) Review medications carefully

If nighttime eating began after starting or changing a medicationespecially certain insomnia drugsthis should be discussed with the prescriber.

In some cases, changing the medication, adjusting timing, or treating a hidden sleep disorder that’s causing arousals can make a major difference.

4) Behavioral and sleep strategies

These strategies are useful for both SRED and NES, though the emphasis differs:

- Consistent sleep schedule: regular wake time is the anchor.

- Reduce sleep deprivation: being overtired can increase parasomnia risk.

- Limit alcohol and avoid sedatives not prescribed for you (they can worsen arousals or impair awareness).

- Stress management: relaxation routines, journaling, therapy, or calming wind-down habits.

-

CBT-I (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia): particularly helpful when insomnia is part of the loop,

and often used for NES-related sleep disruption.

5) Psychological treatment (especially for NES)

NES commonly benefits from therapy that addresses insomnia, stress regulation, and eating-related thoughts/behaviors.

Approaches may include CBT-based therapy, emotion regulation work, and structured routines that support circadian alignment.

If mood or anxiety symptoms are present, treating those can reduce nighttime awakenings and cravings.

6) Medications (doctor-guided only)

In clinical practice, medications are sometimes considered, particularly when:

(a) SRED is severe or dangerous, (b) comorbid conditions are driving episodes, or (c) NES is tied to mood/insomnia patterns.

Some published reviews and clinical discussions describe benefits from certain agents in selected patients, but these decisions are individualized

and should always be handled by a qualified clinician because risks, interactions, and underlying sleep disorders matter a lot.

How to Help During an Episode (Without Making It Worse)

If you live with someone who has suspected SRED, your instinct might be to shake them awake and ask, “WHAT ARE YOU DOING?”

(Understandable.) But sudden awakening can lead to confusion or agitation.

A safer approach is usually:

- Stay calm and keep your voice gentle.

- Avoid startling or physically restraining them unless there’s immediate danger.

- Guide them back toward bed if possible.

- If they’re using appliances or holding something unsafe, prioritize safety and call for help if needed.

When to Seek Professional Help

Consider getting evaluated by a healthcare provider (often a sleep medicine specialist) if:

- Episodes happen more than occasionally (e.g., weekly or more) or are escalating.

- There’s risk of injury, unsafe cooking, or ingestion of non-food items.

- There’s daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, gasping, or restless legs symptoms.

- Nighttime eating began after starting/changing a prescription sleep medication.

- You feel distressed, ashamed, or stuck in a pattern you can’t breakespecially if sleep is suffering.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is sleep-related eating disorder the same as binge eating disorder?

Not usually. Binge eating disorder typically involves being awake and experiencing distress and loss of control during episodes.

SRED involves partial arousal from sleep and often amnesia. A clinician can help distinguish them and check for overlap.

Can kids and teens have these problems?

Yes. Parasomnias are relatively common in younger people, and circadian shifts (like “night owl” patterns) are also common in adolescence.

If nighttime eating is frequent, risky, or distressing, it’s worth a medical evaluationespecially before it becomes a long-running pattern.

Should I just lock the fridge?

Safety modifications can help in SRED, but they’re rarely the whole answer. If SRED is present, the long-term goal is to address triggers

(sleep fragmentation, medication effects, stress, comorbid sleep disorders). Environmental safety can be a bridge, not the destination.

Will I “grow out of it”?

Some parasomnias improve with age, but persistent or dangerous nighttime eating deserves attention nowespecially if a treatable trigger

(like sleep apnea or a medication side effect) is involved.

Experiences: What Living With Sleep-Related Eating Issues Can Feel Like (and What Helps)

People often describe sleep-related eating issues in a way that’s equal parts baffling and frustratinglike your body is running a secret

late-night cooking show, and you’re not even getting credit for the episode.

“The morning scavenger hunt” experience: One common story starts with confusion. Someone wakes up and finds evidence:

a sticky countertop, a half-eaten snack, or a cabinet left open. At first, it can feel like forgetfulness. Then it happens again. And again.

The emotional impact can be bigger than people expect: embarrassment, worry about safety, and the uneasy feeling of not being fully in charge of

what happens at night. What tends to help here is not blame, but data: a simple sleep diary, notes about stress and sleep timing, and

a conversation with a clinician who recognizes that parasomnias are medical conditionsnot personality flaws.

“My partner saw it, but I didn’t” experience: In suspected SRED, a partner or roommate may notice the person looks awakeeyes open,

moving aroundbut also confused and hard to engage. Sometimes the episode ends with the person returning to bed as if nothing happened. The next day,

the person might deny it sincerely because they don’t remember. That mismatch can strain relationships (“Are you hiding this?” “Are you accusing me?”).

People often say the turning point was treating it like a team problem: setting up safety steps without shaming, agreeing on a gentle plan during episodes,

and scheduling a sleep evaluation. When an underlying trigger like sleep apnea or restless legs is found and treated, couples often report a big relief

because the situation finally makes sense.

“I eat because I can’t sleep” experience: With night eating syndrome, the story can feel different. People often report being awake,

feeling restless or anxious, and believing that eating is the only way to quiet the mind enough to fall back asleep. The food isn’t always the “main problem”;

it’s the coping tool that got recruited when sleep became difficult. This is where structured routines can be surprisingly powerful: a consistent wake time,

an evening wind-down that doesn’t start with doom-scrolling, and therapy that targets insomnia and stress loops. Many people also find it helpful to address

daytime patternslike skipping breakfast or having chaotic mealsbecause irregular intake can amplify nighttime hunger signals. The most encouraging part of

these stories is that improvement is often gradual but real: fewer awakenings, less urgency around nighttime eating, and a growing sense of control that’s

rooted in better sleepnot stricter rules.

“The medication plot twist” experience: Another scenario people report is that nighttime eating starts after a new insomnia medication,

or after increasing a dose. They may feel shocked (“Why would a sleep pill make me… not sleep?”), but complex sleep behaviors have been recognized and warned

about with certain prescription sleep drugs. The best outcomes in these cases usually come from quick, clinician-guided action: contacting the prescriber,

reviewing meds, and checking for hidden sleep disorders that cause frequent arousals. People often say the biggest relief was realizing it wasn’t a lack of

disciplineit was a medication effect or a sleep-fragmentation problem that could be addressed.

Across these experiences, one theme repeats: when sleep improves and triggers are treated, nighttime eating behaviors often improve too. And when the approach is

compassionate and practical (safety + medical evaluation + sleep and mental health support), people stop feeling like they’re “failing” and start feeling like

they’re recovering.

Conclusion

Sleep-related eating problems are real, treatable conditionsnot quirky habits and definitely not a character flaw. The key is figuring out which pattern is happening:

SRED (a parasomnia with partial arousal and often amnesia) or NES (a wakeful, circadian-and-insomnia-linked eating pattern with recall).

From there, treatment usually focuses on safety, improving sleep quality, addressing underlying sleep disorders, reviewing medications, and using behavioral or psychological

therapy when needed. If nighttime eating is frequent, risky, or distressing, a healthcare providerespecially a sleep specialistcan help you get answers and a plan that

actually works.