Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The Study Behind the “Triples Risk” Headline

- What Dementia Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- Depression: More Than Feeling “Down”

- How Could Depression Raise Dementia Risk?

- The Big Debate: Cause, Clue, or Both?

- Why the Under-60 Finding Matters More Than You Think

- What to Do With This Information (Without Spiraling)

- Common Questions (Because Your Brain Wants Answers)

- Real-World Experiences (About )

- Bottom Line

- SEO Tags

If you’ve ever googled “Why does my brain feel like it has 37 browser tabs open?” you’re not alone. Depression can mess with mood, sleep, motivation, memory,

and focusbasically the whole “operating system.” Now a large study suggests something even more sobering: depression diagnosed before age 60 may be linked

to about three times the risk of developing dementia later on.

Before anyone panic-buys crossword puzzle books: this doesn’t mean depression “causes” dementia in a straight line, and it definitely doesn’t mean a person

under 60 with depression is destined for cognitive decline. It does mean depression is more than a “mental” issueit’s a whole-body, whole-life health

condition worth treating early and thoroughly. And it means brain health is a long game, not a pop quiz you take at retirement.

The Study Behind the “Triples Risk” Headline

The “triples risk” claim comes from a large population-based cohort study that used decades of Danish registry data and followed more than 1.4 million

adults over time. Researchers compared people with diagnosed depression to similar people without a depression diagnosis, then tracked who later received a

diagnosis of dementia.

What the researchers did

- Identified adults with a clinical diagnosis of depression and matched them to adults without a depression diagnosis.

- Followed participants for many years to see who developed dementia.

- Adjusted analyses for multiple factors that can influence dementia risk (including several health and psychiatric conditions).

- Looked at results by age at depression diagnosis and by time since depression diagnosis.

What they found (in plain English)

Overall, the study found that people with diagnosed depression had a little over double the hazard of dementia compared with those without.

The attention-grabber was what happened when the researchers split people by the age when depression was diagnosed:

- Ages 18–44: about 3.08× higher hazard of dementia later on.

- Ages 45–59: about 2.95× higher hazard.

- Ages 60+: still elevated (about 2.31×), which also fits the idea that late-life depression can overlap with early dementia changes.

So, “triples risk under 60” is a headline-friendly summary of those first two groups. The findings also suggested the association persisted even when

dementia was diagnosed decades after the depression diagnosisan important detail for the “cause vs. clue” debate.

What this does (and doesn’t) mean

A key word here is hazard. This kind of study estimates relative risk over time, not a guaranteed outcome. If a person’s baseline risk of

dementia is low (and it is generally low in midlife), “three times higher” can still be a relatively small absolute number for any one individual.

Headlines often skip that nuance because nuance doesn’t fit on a thumbnail.

What Dementia Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

Dementia isn’t a single disease. It’s a broad term for a decline in thinking, memory, language, reasoning, and/or judgment that’s serious enough to interfere

with everyday life. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause, but there are others (including vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and more).

People also confuse dementia with occasional forgetfulness. Forgetting where you put your keys is annoying. Forgetting what keys are for is a different category.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) can fall in betweennoticeable cognitive changes that don’t fully disrupt daily independence, but may increase the chance of

future dementia for some people.

Dementia is more common after age 65, but it can occur earlier. “Early-onset” Alzheimer’s and other young-onset dementias are much less common, which is why

the under-60 part of this discussion is about future risk, not an immediate expectation.

Depression: More Than Feeling “Down”

Depression is not the same as sadness or grief. Clinical depression is a medical condition that can involve persistent low mood and/or loss of interest, plus

changes in sleep, appetite, energy, concentration, movement, and feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt. It can affect work, relationships, physical

health, and the ability to enjoy life’s basic “good stuff.”

Many people also experience what they call “brain fog” during depressionslower thinking, difficulty concentrating, and problems with memory. That overlap is

one reason depression can be mistaken for cognitive decline and why clinicians sometimes need to look carefully at the full picture.

The good news: depression is treatable. Common evidence-based approaches include psychotherapy (like cognitive behavioral therapy), medications, lifestyle

supports, andwhen neededmore intensive options guided by professionals. Most people improve with appropriate care, even if it takes some trial and error to

find the right combination.

How Could Depression Raise Dementia Risk?

Researchers don’t point to one single “smoking gun.” Instead, depression may increase dementia risk through multiple pathways that can stack together over time.

Think of it less like a light switch and more like a dimmer… that someone keeps accidentally leaning on for years.

1) Brain and body stress systems

Chronic stress and depression are associated with changes in stress hormones and the body’s stress response. Over long periods, that may influence brain regions

involved in memory and learning. This is an active area of research, and scientists are still untangling what’s cause, effect, and feedback loop.

2) Inflammation and immune signaling

Depression has been linked in many studies to changes in inflammatory markers and immune signaling. Separately, neuroinflammation is also being studied in

dementia. The idea isn’t “inflammation equals dementia,” but rather that long-term inflammatory activity could be one piece of a bigger puzzleespecially when

combined with vascular and metabolic risks.

3) Vascular and metabolic factors

What’s good for your heart tends to be good for your brain. High blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and smoking are linked to worse brain outcomes in many

studies. Depression can make these factors harder to manage (and sometimes medications, sleep disruption, or reduced activity can indirectly influence them).

Vascular damage can reduce blood flow and oxygen delivery to brain tissue, contributing to cognitive decline.

4) Lifestyle “drift” during long episodes

Depression can shrink your life. People may withdraw socially, exercise less, sleep poorly, eat less nutritiously, or stop doing cognitively stimulating things.

None of this is about blamedepression is the illness that makes these changes more likely. But those lifestyle shifts may matter because brain health is

supported by movement, connection, sleep, and ongoing learning.

5) Cognitive reserve and social connection

Cognitive reserve is the brain’s ability to cope with damage and keep functioning. Education, mentally stimulating work, hobbies, social engagement, and physical

activity all seem to help build reserve. Depression can reduce engagement with those “reserve-building” activities for long stretches, potentially lowering the

cushion that protects cognition later.

The Big Debate: Cause, Clue, or Both?

Scientists debate whether depression is:

- a risk factor that contributes to dementia development,

- a prodromal symptom (an early sign) of dementia-related brain changes,

- or both, depending on timing, severity, and individual biology.

Late-life depression is often discussed as potentially overlapping with early dementia changes. That’s why the under-60 signal is important: if depression in

early and middle adulthood is linked to dementia diagnoses decades later, it strengthens the argument that depression may sometimes play a contributing role,

not only act as an early symptom.

Still, observational studies can’t prove causation. Depression may also be a marker for other factors (like chronic medical conditions, socioeconomic stressors,

sleep disorders, or substance use) that contribute to dementia risk. Good studies adjust for many confounders, but no study can adjust for everything.

Why the Under-60 Finding Matters More Than You Think

Dementia prevention isn’t a “start at 70” project. Brain health is shaped over decades. If depression in early and midlife is associated with a higher hazard of

dementia later on, that suggests midlife is a meaningful window for intervention:

- Treat depression early so it doesn’t become long-lasting and disabling.

- Protect cardiovascular health (blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, weight, smoking status).

- Maintain routines that keep your brain engaged and your body movingeven in low-energy seasons of life.

- Support sleep, because chronic poor sleep can worsen both mood and cognitive performance.

In other words, it’s not just “watch out for dementia.” It’s “don’t let depression steal your long-term brain budget.”

What to Do With This Information (Without Spiraling)

If you’re under 60 and dealing with depression, the takeaway isn’t fear. The takeaway is leverage. Depression is treatable, and many lifestyle strategies that

support recovery also support brain health. Two birds, one very sensible plan.

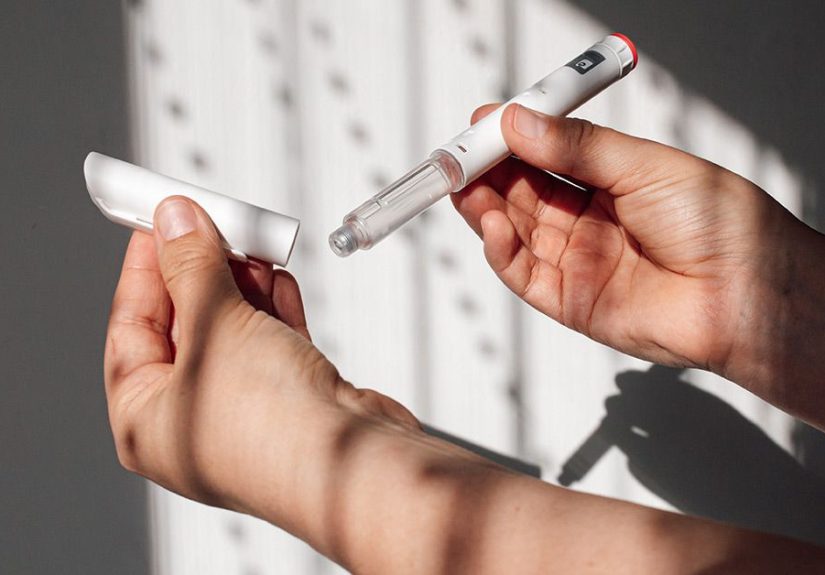

1) Treat depression like the real health condition it is

- Talk to a clinician (primary care or mental health professional) if symptoms last more than a couple of weeks or interfere with life.

- Evidence-based psychotherapy and/or medication can help. Many people do best with a tailored combination.

- Track symptoms and functioningnot just mood. Energy, sleep, motivation, and concentration matter, too.

2) Build “brain-friendly basics” you can actually keep doing

Brain health advice often sounds like a perfect-person checklist. Real life is messier. Start with what’s doable, then stack wins:

- Move regularly: even short walks count. Consistency matters more than intensity.

- Sleep protection: consistent wake time, reduced late-night screen time, and a wind-down routine.

- Nutrition patterns: aim for heart-healthy, brain-friendly basicsmore fiber, more plants, fewer ultra-processed “mystery snacks.”

- Don’t go it alone: social connection is not optional hardware for humans; it’s built-in equipment.

3) Guard your heart to guard your brain

Cardiovascular health and brain health are deeply connected. Managing blood pressure, blood sugar, and other vascular risks is a brain strategy disguised as an

adulting chore. If you need motivation, imagine your arteries as the brain’s delivery service: if the roads are blocked, the packages don’t arrive.

4) Take memory concerns seriouslybut don’t self-diagnose

Depression can mimic cognitive problems, and early cognitive issues can also worsen mood. If you or someone close to you notices meaningful changes in memory,

reasoning, language, personality, or ability to manage daily tasks, it’s worth a medical evaluation. Many causes of cognitive symptoms are treatable or

reversible (like medication side effects, sleep apnea, thyroid issues, vitamin deficiencies, or unmanaged stress).

Common Questions (Because Your Brain Wants Answers)

Does depression cause dementia?

This study shows a strong association, not proof of direct causation. The relationship likely depends on timing, duration, severity, co-existing health

conditions, and social factors. But the persistence of the association when depression occurs decades earlier supports the possibility that depression may

contribute to risk in at least some people.

If I treat depression, does that erase the risk?

We don’t have a simple “risk reset button” answer. However, treating depression can improve sleep, activity, connection, and medical self-carefactors that

plausibly support long-term brain health. It’s a smart bet even if it’s not a guaranteed shield.

Are antidepressants protective?

Research is mixed and complicated. Medication may reduce depression burden for many people, which could indirectly support healthier routines. But medication

effects vary by person, and studies can be confounded by severity (people prescribed medication may have more severe depression). The best approach is

individualized treatment guided by a clinician.

Should adults under 60 be screened for depression?

Many health organizations support routine depression screening in adults in clinical settings, especially when systems are in place for diagnosis, treatment,

and follow-up. Screening is a starting pointnot a label or a life sentence.

Real-World Experiences (About )

Statistics are useful, but people live in stories. Below are composite experiences drawn from common patterns clinicians and patients describeshared here to

make the “depression and brain health” connection feel less abstract and more human.

Experience 1: “I thought I was getting ‘stupid’ at 42”

A 42-year-old project manager notices he can’t hold details in mind like he used to. His email drafts take forever. He rereads the same paragraph five times

and still can’t tell you what it said. He starts Googling early-onset dementia at 2 a.m. (the internet’s favorite time to terrify you). Eventually he visits

his doctor, expecting a memory test to confirm his worst fear. What he learns is that his sleep has collapsed, his anxiety is high, and his mood has been low

for monthsclassic depression and burnout territory.

With therapy, better sleep habits, and a treatment plan, his concentration improves. His “brain fog” doesn’t vanish overnight, but it stops feeling like a

permanent identity. The biggest shift is psychological: he stops interpreting cognitive struggles as personal failure and starts seeing them as symptoms that

respond to care.

Experience 2: The “quiet drift” in midlife

A 55-year-old woman describes depression not as sadness but as shrinking. She stops going to her walking group because she feels “behind.” She cancels plans

because she doesn’t want to be “a drag.” She eats whatever is easiest, sleeps poorly, and can’t find the energy to schedule preventive medical visits. None of

it is dramatic. It’s a slow drift away from the habits that keep her resilient.

When she finally talks to a clinician, her treatment plan focuses on small, repeatable actions: a short walk after lunch, a weekly check-in with a friend, a

consistent bedtime, and therapy that targets negative self-talk. Over time, she rebuilds routines that support both mood and brain healthbecause the same

building blocks that help depression often help cognition: movement, sleep, connection, and purpose.

Experience 3: A family member notices the difference first

A spouse notices changes before the person does: more withdrawal, less laughter, fewer hobbies. They also notice more mistakes at work and a “short fuse.”

Concerned about dementia, they push for an evaluation. The medical workup reveals untreated depression plus high blood pressure and uncontrolled diabetes.

Here’s the underrated lesson: medical care doesn’t have to be either/or. Addressing mood, sleep, and vascular health together can improve day-to-day

functioning, lower long-term risk, and reduce fear. This family finds that a coordinated approachtherapy, medication management, better cardiovascular control,

and gradual lifestyle changescreates momentum. Not perfection. Momentum.

Experience 4: Living with uncertainty without letting it run the show

Many people with depression hear a headline like “triples dementia risk” and feel doomed. But risk is not destiny. One practical way people cope is to focus on

the controllables: consistent treatment, routine medical checkups, physical activity they actually enjoy (yes, dancing in the kitchen counts), and meaningful

social contact. They also learn to track progress by function, not just feelings: “Did I take a walk?” “Did I show up?” “Did I ask for help?” Those are

brain-protective behaviors in disguise.

The main experience-based takeaway is simple: when depression is treated early and supported consistently, people often regain cognitive sharpness and rebuild

habits that protect long-term brain health. That’s not a guarantee of anything decades from nowbut it’s a solid way to stack the odds in your favor.

Bottom Line

A large long-term study found that depression diagnosed before age 60 was associated with roughly a threefold higher hazard of dementia later in life.

That’s a big signalbut not a prophecy. The smartest response isn’t fear; it’s action: treat depression, protect cardiovascular health, keep your brain engaged,

and stay connected to people. Your future self will thank you. And if your future self is anything like most of us, they will also forget where they left the

keysso maybe buy a key hook while you’re at it.

Medical note: This article is for informational purposes and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.