Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Working” Really Means (Spoiler: It’s Not Always Outperformance)

- Why International Has Looked “Broken” for So Long

- So What Changed? Why It’s Feeling Different Now

- The Case for International Diversification (Even If It’s Annoying Sometimes)

- How to Think About International Allocation Without Overcomplicating It

- Risks and Reality Checks (Because Finance Loves Humility)

- So… Is International Diversification Finally Working?

- Investor Experiences: What It Feels Like When Diversification Starts “Paying Off” (About )

- Conclusion

For what felt like roughly 800 investing years (okay, more like a decade-plus), international diversification has had the vibe of a gym membership:

technically good for you, emotionally neglected, and mostly useful as a conversation starter. U.S. stocks kept leading, global stocks kept “having potential,”

and balanced investors kept asking the same question: “Am I diversified… or am I just diluted?”

Then something started to shift. Non-U.S. stocks began putting up real numbers again, headlines started using words like “rotation” and “catch-up,”

and your portfolio’s international sleeve stopped acting like it was grounded. Sohas international diversification finally started working?

The honest answer is: it depends on what you mean by “working.” The more useful answer is: it’s behaving the way diversification is supposed to behave,

and that’s the whole point.

What “Working” Really Means (Spoiler: It’s Not Always Outperformance)

Many investors judge diversification like a reality show competition: whoever wins this season gets all the roses.

But diversification isn’t a “pick the winner” strategyit’s a “don’t get wrecked if one leader stumbles” strategy.

It’s the seatbelt, not the turbocharger.

International diversification “works” when it does at least one of these things:

- Reduces concentration risk (so your results aren’t dependent on one country, one sector, or one investing narrative).

- Improves long-term consistency (because leadership rotates, sometimes slowly, sometimes violently).

- Creates rebalancing opportunities (sell what ran up, buy what got cheaperlike a disciplined bargain hunter).

- Provides currency diversification (because your spending power isn’t married to one currency’s mood swings).

Notice what’s missing: “Beats the S&P 500 every year.” If that’s your definition, then nothing “works” except whatever just worked last year.

And that’s not a planit’s financial whiplash.

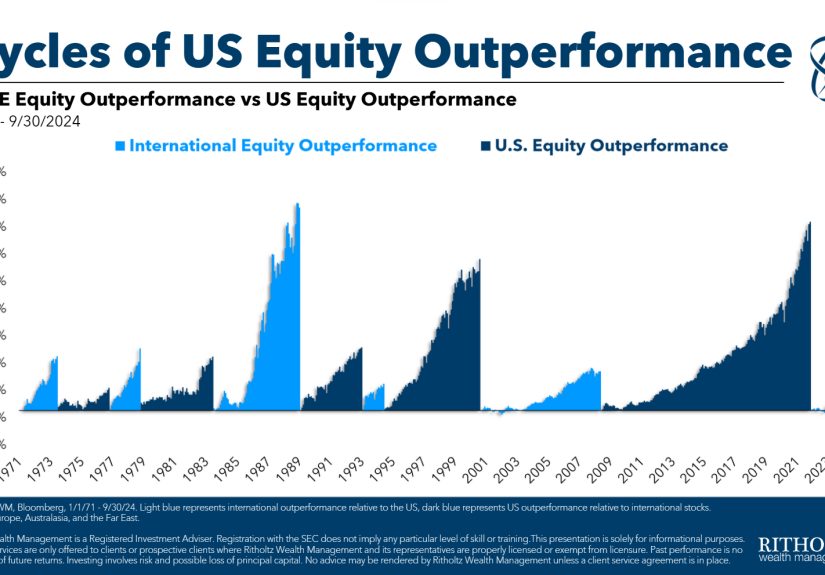

Why International Has Looked “Broken” for So Long

The U.S. market has been unusually dominant since the Global Financial Crisis. That’s not a moral victory. It’s a historical cycle that lasted longer than

most people expectedand long cycles tend to change the way investors think. When something works for a long time, it stops feeling like a cycle and starts

feeling like a law of nature.

1) U.S. tech and “quality growth” became the main story

The U.S. market isn’t just “America Inc.”it’s a particularly heavy mix of mega-cap technology and growth companies.

When those stocks lead, the U.S. index can look unstoppable. Many international indexes, meanwhile, have a different sector mixoften more financials,

industrials, exporters, and “old economy” businesses. That difference matters when markets rotate between growth, value, and cyclical themes.

2) Valuations stretchedespecially in the U.S.

When one market outperforms for a long time, it often becomes more expensive. Higher valuations can be justified by stronger earnings growth,

but they can also raise the bar for future returns. International stocks have frequently traded at a valuation discount to the U.S.,

and discounts don’t last foreverthey either close, or they get even wider (which is not a fun time, but it’s still a time).

3) The U.S. dollar influenced results more than people admit

If you’re a U.S.-based investor, foreign returns are not just “how did the stocks do?” but also “what did the currency do?”

A strong dollar can reduce international returns when translated back into dollars; a weaker dollar can boost them.

This currency effect is not a footnoteit’s a real driver of what your portfolio experiences.

So What Changed? Why It’s Feeling Different Now

When international stocks start outperforming after a long drought, it usually isn’t because the investing universe suddenly discovered

“Europe” or “Japan” on a map. It’s because multiple forces line upvaluations, currencies, economic policy, and sector leadership.

In 2025 especially, a notable theme was that non-U.S. equities outpaced U.S. equities by a wide margin in many measures,

helped by currency moves and shifting sentiment toward cheaper markets.

1) Mean reversion finally showed up to the party

“Mean reversion” is a fancy term for an old truth: leadership rotates. The tricky part is the timing.

Markets can stay out of balance longer than investors can stay patient.

But historically, U.S. and international markets have moved in cyclessometimes long ones.

When the U.S. cycle runs far past its historical average, it doesn’t guarantee a reversal tomorrow,

but it raises the odds that future leadership looks more mixed than the recent past.

2) A weaker dollar can make international returns look surprisingly strong

If the dollar declines while foreign markets rise (or even if they rise modestly), the combination can create powerful “in dollar terms” returns.

This is one of the reasons international performance can feel like it “suddenly” improved: the currency tailwind can do real work.

The reverse is also truewhen the dollar is strong, international can feel like it’s running uphill in flip-flops.

3) Valuation gaps started to matter again

When investors get nervous about lofty pricing in one market, they start shopping elsewhereespecially if they can buy similar earnings streams

for less. International markets often include globally competitive companies (in healthcare, industrials, consumer brands, semiconductors supply chains,

and automation) at lower starting valuations than comparable U.S. peers. When sentiment shifts, valuation discounts can narrow,

and that narrowing can add fuel to returns.

4) Different economic and policy paths created different winners

The world doesn’t run on one central bank or one fiscal policy. Interest-rate paths, government spending, industrial policy,

and trade dynamics can diverge across regions. Those divergences affect sector leadership, profit margins, and capital flows.

When the U.S. is the only place with growth, money crowds in. When growth and opportunity broaden, money spreads out.

The Case for International Diversification (Even If It’s Annoying Sometimes)

It’s not a bet against the U.S.

Owning international stocks isn’t “anti-America.” It’s pro-portfolio design.

U.S. investors already have heavy exposure to the U.S. economy through jobs, housing, and spending.

Adding international equities can help reduce “home bias” and diversify the sources of return.

It reduces single-market risk

Imagine if one country’s market becomes extremely concentratedby sector, by a handful of mega-cap names,

or by one narrative (like AI, rate cuts, or “this time is different”). Concentration can be profitable right up until it isn’t.

International diversification is one way to avoid turning your portfolio into a one-country startup pitch deck.

It’s a rebalancing engine, not a performance trophy

Rebalancing is the quiet superpower of diversified portfolios. When the U.S. runs ahead for years,

a disciplined investor trims U.S. exposure back toward target and adds to what’s lagging.

That feels wrong in the moment (because winners feel safe), but it is one of the few systematic ways investors “buy low and sell high”

without needing psychic powers.

How to Think About International Allocation Without Overcomplicating It

You don’t need a 47-country spreadsheet or a globe-shaped dartboard. Most investors can cover the international category with broad, low-cost funds

(developed markets and, optionally, emerging markets), and then let rebalancing do the heavy lifting.

A practical framework (not a commandment)

- Start with a clear target: Some investors use global market weights as a reference; others prefer a simpler fixed range.

- Use broad exposure: A total international or developed-markets fund can capture thousands of companies across regions.

- Decide on emerging markets intentionally: They may add diversification and growth potential, but also higher volatility and unique risks.

- Rebalance on a schedule: Annual or semiannual reviews can prevent performance-chasing.

The goal isn’t perfection. The goal is a portfolio that survives multiple decades, multiple regimes, multiple booms, and multiple “new eras”

that turn out to be… regular eras with better marketing.

Risks and Reality Checks (Because Finance Loves Humility)

International stocks can lag for long stretches

They can, and they have. If you own international equities expecting constant outperformance, you’ll end up rotating at exactly the wrong time.

The benefit of diversification is not that it wins every yearit’s that it doesn’t rely on one winner.

Currency works both ways

A weaker dollar can boost returns; a stronger dollar can reduce them. Currency adds volatility.

Over very long horizons, currency effects can wash out somewhat, but in real-life investor timefive years, ten yearsthey matter.

Geopolitics and governance differ across markets

International investing includes political risk, regulatory differences, and market-structure variation.

That’s not an argument to avoid itit’s an argument to diversify within it and size it appropriately.

So… Is International Diversification Finally Working?

If by “working” you mean “international stocks are contributing again,” then yesrecent performance has reminded investors why global diversification exists.

If by “working” you mean “it will now outperform forever,” then nomarkets don’t sign those contracts.

The more important takeaway is that diversification is doing what it’s supposed to do: giving you multiple ways to win (and fewer ways to lose big).

The U.S. can remain a strong long-term holding while international equities help balance valuations, sector exposure, and currency risk.

In other words: it’s not a U.S. vs. international cage match. It’s a portfolio.

Investor Experiences: What It Feels Like When Diversification Starts “Paying Off” (About )

If you want to understand international diversification, don’t start with a chartstart with the emotions investors report when the cycle turns.

For years, many diversified investors described their international allocation as “dead weight.” They’d look at account statements and feel like that

slice existed solely to make them feel responsible, like eating a salad next to a cheeseburger. The frustration was rarely intellectual.

It was psychological: “I did the prudent thing… and I’m being punished.”

Then, when international markets began outperforming, the emotional experience often flipped in a weird way.

First came disbelief: “Waitwhy is Europe up more than the U.S.?” Next came suspicion: “This can’t last.”

And then came the most dangerous stage: temptation. Investors who had ignored international exposure for years suddenly wanted to increase it

dramaticallybecause now it looked like the “hot trade.” That’s the classic trap: diversification becomes popular precisely when it becomes less needed

as a behavioral guardrail.

Another common experience is the rebalancing dilemma. Imagine a balanced investor who kept a steady 60/40 stock split and a meaningful international

allocation. During the long U.S.-led stretch, rebalancing meant regularly trimming U.S. winners and adding to international laggards.

That felt like walking into a party and leaving early because you promised yourself you’d be “responsible.” It wasn’t fun. It wasn’t glamorous.

But when international performance improved, those boring rebalancing decisions started to look brilliant in hindsightwithout requiring a prediction.

Investors also report a “currency surprise” moment. They’ll notice international holdings rising faster than expected and assume foreign companies must be

crushing earningsonly to realize part of the boost came from the dollar weakening. That realization is often the moment investors truly understand

currency diversification: they weren’t just buying foreign stocks, they were buying exposure to a different set of economic forces.

It’s not magic, but it is a reminder that returns have more than one ingredient.

Finally, many investors describe diversification “working” not as a victory lap, but as relief. When portfolios aren’t dependent on one country or one

sector narrative, investors feel less pressure to forecast the future. They stop doomscrolling market commentary as if it’s weather radar for their

retirement. They’re still invested, still exposed to risk, but less emotionally fragile. That’s a real benefitone that doesn’t show up cleanly in a

single-year performance chart, but matters a lot over a lifetime of investing.

Conclusion

International diversification isn’t a trend. It’s a structure. Sometimes it’s the annoying part of the portfolio, and sometimes it’s the part that saves

you from being overconfident at exactly the wrong time. If it feels like it’s “finally working,” that may simply mean markets are reminding us of an old,

boring truth: leadership rotates, and diversified investors don’t need to guess when.