Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick MI Foundation: Spirit + Skills (So the Processes Actually Work)

- Process 1: Engaging (Shall We Walk Together?)

- Process 2: Focusing (Where Are We Going?)

- Process 3: Evoking (Why Might You Want to Change?)

- Process 4: Planning (How Will You Do It?)

- Putting It All Together: The Four Processes as a “Conversation GPS”

- Common MI Mistakes (That Even Well-Meaning Humans Make)

- Why the Four Processes Matter (Even If You Never Say “Motivational Interviewing” Out Loud)

- of Real-World Experiences (What These Processes Feel Like in Practice)

- Conclusion

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is what happens when “being helpful” stops sounding like a lecture and starts

sounding like a conversation. It’s a practical, evidence-based communication style designed to strengthen a

person’s own motivation and commitment to changewithout wrestling them into it.

If you’ve ever tried to convince someone to change a habit (or, honestly, tried to convince yourself),

you already know the big plot twist: people argue hardest for the position they’re currently ineven if it’s

the position making them miserable. MI is built around a smarter idea: instead of piling on reasons, you

help people say their own reasons out loud. That’s where change gets traction.

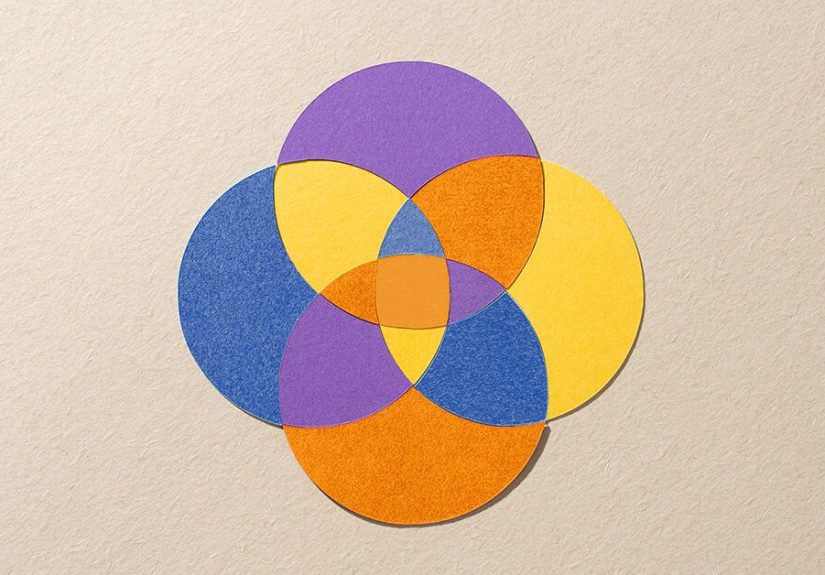

In modern MI, the conversation “flow” is often described using four overlapping processes:

Engaging, Focusing, Evoking, and Planning.

These aren’t rigid steps like “press 1 for motivation.” They’re more like a playlist you can shuffle:

you move forward, you circle back, you repeat the chorus until it finally sticks.

Quick MI Foundation: Spirit + Skills (So the Processes Actually Work)

Before we dive into the four processes, two MI basics matter because they show up everywhere:

the spirit of MI and the core skills.

The “spirit” of MI (how you show up)

- Partnership: You work with the person, not on them.

- Acceptance: You respect autonomy and meet the person where they are.

- Compassion: You actively prioritize the person’s well-being.

- Evocation: You draw out what’s already inside them (values, goals, reasons).

Translation: MI isn’t a “gotcha” technique. It’s not sales. It’s not sneaky. It’s a way of talking that

makes change feel less like punishment and more like a choice.

Core skills: OARS (what you do in the moment)

- Open-ended questions

- Affirmations

- Reflections (reflective listening)

- Summaries

OARS are the tools; the four processes are the game plan. Same tools, different purpose depending on where

you are in the conversation.

Process 1: Engaging (Shall We Walk Together?)

Engaging is the relational foundationbuilding a working relationship that feels safe,

respectful, and collaborative. If engaging is shaky, everything else gets wobbly. You can’t “evoke change talk”

from someone who doesn’t trust you… unless you count sarcasm as a form of change talk. (It is not.)

What engaging looks like

- Showing genuine curiosity about the person’s perspective

- Listening for meaning (not just facts)

- Affirming strengths and autonomy (“You know yourself best.”)

- Asking permission before sensitive topics or advice

- Reducing “discord” (tension, defensiveness, power struggles)

A mini example (engaging in real life)

You: “Would it be okay if we talked for a minute about sleep and how it’s been affecting your days?”

Them: “Sure, but I’ve tried everything.”

You (reflection): “You’re worn out, and you’re also tired of hearing the same tips that don’t fit your life.”

Them: “Exactly.”

That “Exactly” is gold. Engaging isn’t about being charming; it’s about being accurate. When people feel understood,

they stop defending themselves long enough to think.

Common engaging traps (and how to escape)

- The righting reflex: jumping in to fix. Antidote: reflect first, advise later (if invited).

- Question–answer trap: rapid-fire questions that feel like an interview. Antidote: more reflections, fewer interrogations.

- Expert trap: acting like the person is a homework assignment. Antidote: partnership language (“Let’s figure this out together.”).

If the conversation feels tense, rushed, or “prickly,” don’t push forward to focusing or evoking.

Go back to engaging. In MI, stepping backward is not failureit’s navigation.

Process 2: Focusing (Where Are We Going?)

Once you’ve got engagement, focusing is the ongoing process of choosingand maintaininga clear direction.

MI isn’t just a supportive chat; it’s a purposeful conversation about change. But the focus has to be

shared, not imposed.

What focusing does

- Turns a vague “I should do better” into a workable target (“walk 3 days/week,” “cut back on soda,” “call my doctor”)

- Prevents “topic pinball” (where every new sentence is a new life crisis)

- Creates clarity about what the conversation is actually for

How focusing sounds

- “What feels most important to tackle first?”

- “Of the things you mentionedstress, sleep, and smokingwhere should we start today?”

- “What would you like to be different a month from now?”

Sometimes the setting provides a default focus (e.g., a health visit, a counseling mandate, a coaching goal).

Even then, MI asks you to negotiate the focus so the person has ownership. You can be transparent:

“Here’s what brought us herehow does that fit with what you want?”

Practical focusing tool: “agenda mapping” (aka the polite menu)

You reflect what you’re hearing, name a few possible directions, and let the person choose. It’s shockingly effective.

Humans like options. Humans like autonomy. Humans especially like autonomy when they’re tired of being told what to do.

You: “I’m hearing a few possible areas: your energy, your drinking on weeknights, and how stress hits you after work. Which one would be most helpful to focus on today?”

Them: “The after-work drinking. That’s where it spirals.”

Now you’ve got focus. And here’s the key MI logic: focusing needs to come before evoking.

Otherwise you’re evoking motivation… for a target that’s still foggy.

Process 3: Evoking (Why Might You Want to Change?)

If engaging is the relationship and focusing is the destination, evoking is the engine.

This is where MI becomes distinct: you intentionally draw out the person’s internal motivationsespecially

change talk, the language that favors movement toward change.

A simple way to remember change talk is DARN–CAT:

Desire, Ability, Reasons, Need (preparatory);

then Commitment, Activation, Taking steps (mobilizing).

The more a person hears themselves argue for change, the more likely they are to move. Meanwhile,

if you do all the arguing, they practice the opposite: sustain talk (“It’s not that bad,” “I can’t,” “It won’t work”).

MI tries to reduce accidental sustain-talk training.

Evoking strategies that work (without turning into a motivational poster)

- Evocative questions: “What worries you about things staying the same?”

- Elaboration: “Tell me more about that.”

- Looking back / looking forward: “When was it better?” “If nothing changes, where might this be in a year?”

- Exploring values: “What matters most to you here?”

- Rulers (0–10): importance and confidence scaling (“Why a 6 and not a 2?”)

- Decisional balance (carefully): “What do you like about the current pattern? And what are the downsides?”

Evoking in action: a short dialogue

You: “On a scale from 0 to 10, how important is it to cut back on weeknight drinking?”

Them: “Probably a 7.”

You: “Why a 7 and not a 3?”

Them: “Because I hate waking up foggy, and I’m not being present with my kids.”

You (reflection + affirmation): “You want your mornings backand you care a lot about showing up as the parent you want to be.”

Them: “Yeah. I’m tired of feeling like I’m missing my own life.”

Notice what happened: you didn’t “convince” them. You created conditions where their reasons surfaced.

Evoking is less about hype and more about precision listeningcatching change talk and reflecting it back

so it gets louder.

How you know you’re evoking well

- The person is doing most of the talking

- You’re hearing more DARN language (want/can/why/need)

- Resistance is lower because autonomy is respected

- There’s increasing movement toward commitment (“I might,” “I’m ready,” “I will”)

If evoking stalls, it often means one of two things: the focus isn’t clear enough, or engagement took a hit.

That’s your cue to back upbecause MI is recursive by design.

Process 4: Planning (How Will You Do It?)

Planning is about developing a realistic action plan when the person shows readiness.

Not everyone reaches planning in a single conversationand MI doesn’t force it. In fact, one classic pitfall is

premature planning: the helper gets excited and starts building a plan while the person is still ambivalent.

That usually triggers pushback (because now they’re defending the status quo again).

Signs it might be time to plan

- More commitment language (“I will,” “I’m going to,” “I’ve decided”)

- Activation (“I’m ready,” “I’m willing,” “I want to start soon”)

- Taking steps (they’ve already tried something, even small)

- Less “yes, but…” and more “okay, how?”

What MI-consistent planning looks like

- Ask permission: “Would it be okay if we talked about a next step?”

- Offer a menu: choices increase autonomy and follow-through

- Keep it specific: small, doable steps beat heroic overhauls

- Troubleshoot gently: “What might get in the way?”

- Strengthen self-efficacy: “What has worked for you before?”

A planning example (collaborative, not bossy)

You: “Given what you said about mornings and being present with your kids, what feels like a first step you’d actually do?”

Them: “No drinking Monday through Thursday. I can handle weekends later.”

You: “That’s clear and specific. What would make that easier on a stressful Tuesday?”

Them: “I need a replacementmaybe a walk or tea, and I’ll text my friend instead of stopping at the store.”

You (summary): “So the plan is: weekdays alcohol-free, swap in a walk or tea after work, and use your friend as support when stress spikes.”

Planning is still MI: you’re guiding, not steering. The person owns the plan, and you help make it sturdier.

If ambivalence flares back up, you don’t scold ityou shift back to evoking (or even focusing/engaging).

Putting It All Together: The Four Processes as a “Conversation GPS”

Here’s a practical way to think about the 4 processes of motivational interviewing:

- Engaging: “Do we have a relationship strong enough to talk honestly?”

- Focusing: “Are we talking about the right change target?”

- Evoking: “Are we drawing out their reasons (not mine)?”

- Planning: “Are they readyand do we have a doable next step?”

In a 10–15 minute real-world conversation (primary care, coaching, school counseling, case management),

you might do a “micro” version: engage quickly, name a focus, evoke a few lines of change talk, and if readiness

is there, agree on one small step. MI scales down surprisingly well when you use the processes on purpose.

Common MI Mistakes (That Even Well-Meaning Humans Make)

1) Giving advice too early

Advice isn’t evil. Uninvited advice is just… loud. Ask permission first, and tailor it to what they care about.

2) Debating sustain talk

If they say, “I can’t,” and you say, “Yes you can,” congratulationsyou’re now in a motivational arm-wrestling match.

Reflect it instead: “It feels overwhelming,” then evoke: “What would make it even 5% more possible?”

3) Skipping focus

Without focus, your evoking becomes motivational soup: lots of feelings, no direction.

4) Treating planning like a takeover

If your plan is perfect but theirs is missing, guess whose plan gets followed? (Hint: not yours.)

Why the Four Processes Matter (Even If You Never Say “Motivational Interviewing” Out Loud)

You can use the four processes without “doing MI” as a formal intervention. They’re a framework for any conversation

where change is on the table: health behaviors, substance use, mental health, exercise, medication adherence, parenting

routines, study habits, financial behavior, you name it.

The big win is that the processes keep you from doing the two things that most reliably backfire:

(1) trying to force change, and (2) trying to plan change before the person is ready.

Instead, you build engagement, clarify focus, evoke motivation, and then plan in a way that respects autonomy.

of Real-World Experiences (What These Processes Feel Like in Practice)

People often imagine MI as a smooth, cinematic conversation where the other person suddenly says,

“You’re right. I’m ready to change.” In real life, the four processes feel more like driving with a GPS that

occasionally reroutes because someone (possibly you) missed a turn.

Engaging often shows up as a surprising moment of relief. A nurse in a busy clinic might notice that

the patient’s shoulders drop when she says, “You’re the expert on your lifecan you tell me what a good day looks like?”

That one line changes the emotional temperature. In schools, counselors describe engaging as the moment a student stops

giving “fine” answers and starts talking like a real person: “Honestly, I’m stressed all the time.” In coaching settings,

engaging can happen quickly when the coach reflects the client’s frustration without judgment: “You’re not lazyyou’re exhausted.”

Focusing is where conversations get realand sometimes uncomfortable. In addiction treatment, focusing may mean

gently naming the discrepancy between someone’s goals and their current pattern, without shaming them. In fitness or nutrition work,

focusing often looks like shrinking an overwhelming goal into one target that matters: “Is this about weight, energy, confidence, or all three?

If we picked one for this month, which would change the most for you?” People frequently report that focusing is the first time the change feels

“handle-able” instead of like a foggy life sentence.

Evoking is where you can almost hear the gears turn. Practitioners often describe it as “catching” a line that matters

and reflecting it back so the person can hear themselves. A client says, “I hate how short I am with my kids,” and the helper reflects,

“Being the parent you want to be is really important to you.” That reflection can lead to more change talk: “Yeah… I don’t want them to remember me like this.”

Evoking also includes patiencebecause sometimes the first five minutes are sustain talk. The experience is learning not to panic.

Instead of arguing, you stay curious until the person’s own reasons begin to surface.

Planning tends to feel less dramatic and more practicallike building a small bridge. In primary care, planning might be:

“I’ll walk for 10 minutes after dinner on Tuesdays and Thursdays.” In therapy, it might be: “I’ll call my sponsor before I drive past the bar.”

In everyday family life, planning could be: “I’ll put my phone on the counter while I help with homework.” The shared experience across settings is that

MI-consistent plans are usually smaller than people expectand more successful because the person chose them. And if the plan falls apart?

The MI move isn’t punishment. It’s a reroute: back to engaging, refocusing, and evoking what the person still wants.

Conclusion

The 4 processes of motivational interviewingengaging, focusing, evoking, and planninggive you a simple way to stay helpful without becoming pushy.

You build a real working relationship, choose a clear direction together, draw out the person’s own motivation, and only then move into action planning.

And when the conversation gets messy (because humans), you don’t “fail”you shift processes and keep going.