Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What is necrotizing pancreatitis?

- What causes necrotizing pancreatitis?

- Symptoms: What does necrotizing pancreatitis feel like?

- How doctors diagnose necrotizing pancreatitis

- Treatment: What actually happens in the hospital

- Procedures and surgery: the “step-up approach” explained like a human

- Recovery, complications, and long-term outlook

- When to seek emergency care

- Frequently asked questions

- Real-world experiences with necrotizing pancreatitis (what the journey can feel like)

If your pancreas had a “Do Not Disturb” sign, necrotizing pancreatitis would be the moment someone ignores it, barges in, and turns the lights on full blast.

It’s a serious complication of acute pancreatitis where part of the pancreas (and sometimes nearby tissue) loses blood supply and dies (necrosis). The topic is heavy,

but the goal here is simple: help you understand what it is, what it looks like, how it’s diagnosed, and how it’s treatedwithout turning this into a medical textbook

or a horror movie.

Important note: this article is educational and not a substitute for medical care. Necrotizing pancreatitis can become life-threatening. If someone has severe belly pain,

fever, confusion, or trouble breathingtreat it like an emergency.

What is necrotizing pancreatitis?

Necrotizing pancreatitis is a form of severe pancreatitis where inflammation and injury disrupt blood flow to pancreatic tissue (and/or surrounding tissue),

leading to tissue death. Not everyone with pancreatitis develops necrosismany cases are mild and improve with supportive care. But when necrosis happens, it raises the stakes,

mainly because dead tissue can become infected and trigger dangerous complications.

A quick pancreas refresher (because it matters)

Your pancreas sits behind your stomach and has two big jobs: it makes digestive enzymes (exocrine function) and hormones like insulin (endocrine function).

In pancreatitis, those enzymes can get activated too early, irritating the pancreas instead of calmly waiting to help digest lunch.

With severe inflammation, swelling and microvascular injury can choke off blood supplysetting the stage for necrosis.

Sterile necrosis vs infected necrosis

Clinicians often divide necrotizing pancreatitis into two categories:

- Sterile necrosis: dead tissue is present, but there’s no infection. This can sometimes be managed without procedures.

- Infected necrosis: bacteria (usually from the gut) infect the dead tissue. This often requires antibiotics and, in many cases, drainage or removal of necrotic material.

What causes necrotizing pancreatitis?

Necrotizing pancreatitis usually starts as acute pancreatitis. The same triggers that cause acute pancreatitis can, in a smaller subset of cases,

escalate into necrosisespecially when inflammation is severe or prolonged.

Common triggers

- Gallstones: can block the bile/pancreatic ducts and set off pancreatitis.

- Heavy alcohol use: a major cause of pancreatitis in many adults.

- Very high triglycerides: can inflame the pancreas.

- Certain medications: some drugs are linked to pancreatitis in susceptible people.

- ERCP (an endoscopic bile duct procedure): can sometimes trigger pancreatitis as a complication.

- Trauma, infections, metabolic issues, or genetic factors: less common, but possible.

Why “necrotizing” happens (the short version)

Severe inflammation can cause capillary leak, swelling, and micro-clotting in tiny blood vessels. When oxygen delivery drops, tissue becomes ischemic.

If that injury is extensive and irreversible, necrosis develops. Think of it as a supply-chain collapse: the tissue can’t get what it needs to survive.

Symptoms: What does necrotizing pancreatitis feel like?

Early symptoms can look like “regular” acute pancreatitis. The difference is often severity, persistence, and system-wide impact.

Some clues show up when a person fails to improveor worsensafter the initial pancreatitis episode.

Common symptoms

- Severe upper abdominal pain that may spread to the back and last for days

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever (especially concerning if it appears later)

- Fast heart rate

- Swollen or tender abdomen

- Weakness, sweating, dehydration

Red flags that suggest severe disease or infection

- Symptoms that worsen after a brief improvement

- Low blood pressure, dizziness, fainting

- Shortness of breath or low oxygen

- Confusion or unusual sleepiness

- Persistent high fever or rising white blood cell count

Example: Someone develops pancreatitis from gallstones and is hospitalized. Pain slowly improves for a few days, then spikes again with fever and worsening fatigue.

That “second wave” can be a clue that necrosis is present and may be infectedsomething the medical team will investigate quickly.

How doctors diagnose necrotizing pancreatitis

Diagnosis usually combines symptoms, bloodwork, and imaging. The timing matters: necrosis may not be fully visible on imaging in the earliest hours of illness,

so clinicians match tests to the phase of disease.

Blood tests

- Lipase (and sometimes amylase): often elevated in acute pancreatitis

- CBC: checks white blood cell count (infection/inflammation) and anemia

- Metabolic panel: kidney function, electrolytes, liver tests

- CRP (C-reactive protein) and other markers: can reflect severity/inflammation

- Blood glucose: pancreatitis can disrupt insulin regulation

Imaging tests

- Contrast-enhanced CT scan: commonly used to identify pancreatic necrosis and related collections (often more informative after the early phase).

- MRI/MRCP: can help evaluate ductal anatomy and collections, sometimes when CT isn’t ideal.

- Ultrasound: helpful for identifying gallstones or biliary dilation.

Pancreatic collections: “walled-off necrosis” and why 4 weeks is a big deal

Severe pancreatitis can create fluid and debris collections around the pancreas. Over time, some collections develop a defined capsule.

When necrotic material becomes encapsulated later in the course, it may be called walled-off necrosis.

This matters because many interventions are safer and more effective after collections mature and form a wall.

Treatment: What actually happens in the hospital

Treating necrotizing pancreatitis is usually a marathon, not a sprint. Early care focuses on stabilizing the body. Later care targets complications such as infection,

persistent symptoms, or obstruction caused by collections.

1) Early supportive care (the “keep the engine running” phase)

- IV fluids: to support circulation and organ perfusion

- Pain control: carefully managed (pain is not a character-building exercise)

- Oxygen/respiratory support: if breathing is affected

- Frequent monitoring: blood pressure, urine output, labs, and signs of organ dysfunction

- ICU care: for severe disease, shock, breathing problems, or multi-organ stress

2) Nutrition: feeding the person, not the inflammation

A modern theme in pancreatitis care is: don’t starve the gut if you can help it. If a person can eat and tolerate food, clinicians often restart oral intake.

If not, enteral nutrition (tube feeding into the stomach or small intestine) may be usedespecially in severe casesto support healing and reduce infectious complications.

Total parenteral nutrition (nutrition through veins) is generally reserved for situations where the gut can’t be used.

3) Antibiotics: not routine, but crucial when infection is suspected

One of the most important “what not to do” points: preventive antibiotics are not recommended for sterile necrosis.

But if infected necrosis is suspected or confirmed, antibiotics become part of the planoften to control infection and buy time until a procedure can be performed more safely.

The antibiotic choice depends on the clinical situation and local resistance patterns.

4) Treating the trigger (so it doesn’t happen again)

- Gallstones: may require ERCP in select situations (like cholangitis/obstruction) and later gallbladder removal when appropriate.

- Alcohol-related pancreatitis: stopping alcohol is key to preventing recurrence.

- High triglycerides: requires targeted treatment and long-term management.

- Medication-related: the offending drug may be discontinued when clinically appropriate.

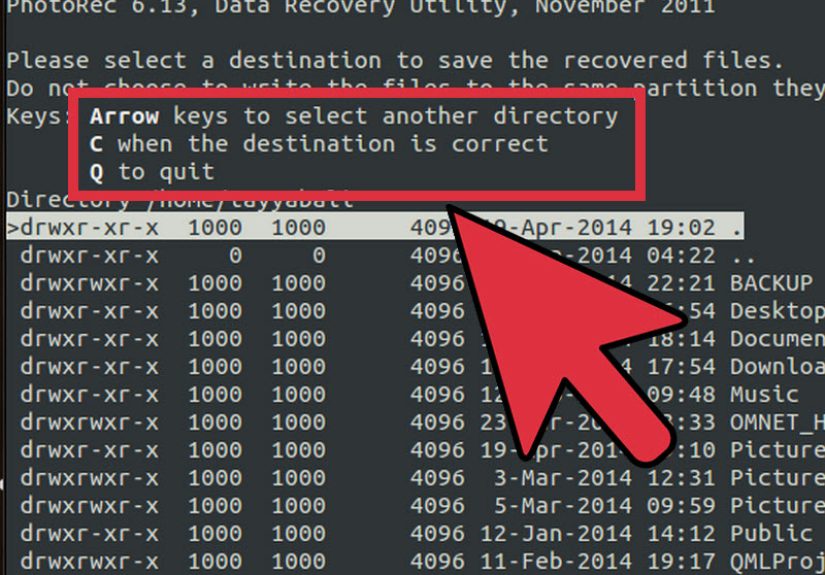

Procedures and surgery: the “step-up approach” explained like a human

If necrosis becomes infected or causes significant ongoing problems (persistent pain, inability to eat, obstruction, or systemic illness),

many centers use a step-up approach: start with the least invasive option, then “step up” only if needed.

This strategy aims to reduce complications compared with immediate open surgery.

Step 1: Drainage (often first)

- Endoscopic drainage: an endoscope is used (often with ultrasound guidance) to create a pathway for drainage into the stomach or intestine.

- Percutaneous catheter drainage: a radiologist places a drain through the skin into the collection.

Step 2: Minimally invasive debridement/necrosectomy (if drainage isn’t enough)

- Endoscopic necrosectomy: removing necrotic material through an endoscope in specialized centers.

- Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD): a minimally invasive surgical technique using an existing drainage path.

Step 3: Open surgery (less common, more selective)

Open surgical necrosectomy is generally reserved for situations where less invasive approaches fail or when complications demand it.

The overall trend has moved toward minimally invasive and endoscopic strategies when feasible and when expertise is available.

Recovery, complications, and long-term outlook

Recovery can be straightforward for some and complicated for others. The course depends on the amount of necrosis, whether infection occurs,

the presence of organ failure, and how the body responds to supportive care and interventions.

Possible complications

- Infected necrosis and sepsis-like systemic illness

- Walled-off necrosis or other pancreatic fluid collections

- Pancreatic duct leaks or fistulas

- Diabetes (if insulin-producing tissue is affected)

- Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (trouble digesting fats; may require enzyme supplements)

- Recurrent pancreatitis if triggers aren’t addressed

What follow-up can look like

Follow-up often includes imaging to ensure collections are resolving, lab monitoring, nutrition support, and management of underlying causes

(like gallbladder disease, triglycerides, or alcohol use). Some people need a longer recovery phase with strength rebuilding and dietary adjustments.

When to seek emergency care

Get urgent medical attention if someone has severe abdominal pain (especially with vomiting), fever, confusion, fainting, trouble breathing,

or signs of dehydration. With necrotizing pancreatitis, delays can be dangerousthis is not the time for “let’s see how it feels tomorrow.”

Frequently asked questions

Is necrotizing pancreatitis the same as pancreatic cancer?

No. Necrotizing pancreatitis is an inflammatory condition with tissue death due to severe pancreatitis. Pancreatic cancer is a malignancy.

They are different diseases, though both can be serious and both warrant prompt medical evaluation.

Can necrotizing pancreatitis heal on its own?

Some people with sterile necrosis improve with supportive care and careful monitoring. Others develop complications that require drainage,

antibiotics, and/or procedures. The key is that decisions depend on symptoms, infection status, and overall stability.

How long does recovery take?

Mild pancreatitis may improve in days. Necrotizing pancreatitis can require weeks of care and sometimes longer recoveryespecially if there’s infection or intervention.

Many people gradually regain normal eating and strength, but follow-up is important.

Real-world experiences with necrotizing pancreatitis (what the journey can feel like)

The medical facts matter, but lived experience is often what people remember: the uncertainty, the waiting, the small wins, and the “I cannot believe my body is doing this”

moments. The stories below are composite examples inspired by common clinical patternsshared to help readers feel less alone, not to replace medical advice.

Experience #1: “It started like food poisoning… until it didn’t.”

One person describes sudden upper abdominal pain that seemed like a bad meal or a stomach bug. Within hours, the pain was intense and wouldn’t quit.

At the hospital, blood tests suggested pancreatitis. The first few days blurred together: IV fluids, nausea, and pain control. Then something changedfever showed up,

the heart rate climbed, and fatigue felt “heavy,” like walking through wet cement. Imaging later revealed necrosis. The emotional whiplash was real:

“I thought I was improving. Then it felt like I was back at square one.”

What helped most wasn’t a magical shortcut (there isn’t one). It was a coordinated team and clear communication: why antibiotics weren’t automatic,

why eating might be paused or restarted, and why procedures were sometimes delayed until collections matured. Knowing the “why” made the waiting less terrifying.

Experience #2: The surprise of tube feeding (and the relief of finally getting strength back)

Another common experience is the shock of needing enteral nutrition. Many people assume, “If my pancreas is mad, shouldn’t I stop all food forever?”

But clinicians often aim to support the gut when possible. Patients describe a turning point when nutrition finally improved energy:

less dizziness on standing, fewer “crash” moments, and the first time a short walk down the hallway didn’t feel like climbing a mountain.

It’s not glamorousbut it’s progress.

Experience #3: “Why can’t they just remove it right away?”

Families often struggle with the idea that doctors may wait before aggressively removing necrotic tissue. The instinct is understandable:

dead tissue sounds like something you’d want gone immediately. In practice, many teams use a step-up strategy and delay invasive interventions when the patient can tolerate it,

because procedures can be safer and more effective once collections develop a defined wall. Patients remember this phase as mentally exhausting:

daily labs, repeat imaging discussions, and the constant question“Are we turning a corner yet?”

When intervention is needed, the “step-up” approach can also feel like a lot: first a drain, then maybe an endoscopic procedure, then another.

People sometimes feel discouraged by multiple steps until someone reframes it: each step is a chance to solve the problem with less trauma to the body

than jumping straight to the most invasive option.

Experience #4: Life after discharge (the part nobody prepares you for)

Discharge can feel like freedomand like stepping off a cliff without a map. Many people describe lingering fatigue, appetite changes,

anxiety about recurrence, and frustration with “normal” meals that suddenly don’t sit right. Follow-up becomes the new routine:

managing triglycerides, scheduling gallbladder surgery if gallstones were involved, avoiding alcohol, and watching for signs of diabetes or digestive issues.

The best recoveries tend to include realistic expectations and support: gradual return to activity, nutrition guidance, and a plan for symptoms that should trigger a call.

People often say the most helpful sentence from a clinician was something like: “Healing isn’t linear. Some days will feel backwardbut overall, we’re moving forward.”

And yes, celebrating tiny victories is allowed. If you walked to the mailbox without needing a nap, that counts.