Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First Aid: What to Do Immediately (Before You Make It Worse)

- 1) Check the Linux Trash on the Pen Drive (Yes, It Might Be That Simple)

- 2) Restore from Backups, Sync, or “Past You Was Smarter Than Present You”

- 3) Make a Disk Image First (The Golden Rule of USB Data Recovery)

- 4) Use TestDisk to Undelete Files (Best When You Want Filenames Back)

- 5) Use PhotoRec for File Carving (When the File System Is Toast)

- 6) extundelete (ext3/ext4 Only): Journal-Based Undelete on Linux File Systems

- 7) ntfsundelete for NTFS USB Drives (If Your Pen Drive Was Used With Windows)

- 8) Foremost/Scalpel and Sleuth Kit: Forensic-Style Recovery When You Need Options

- How to Choose the Right Method (Quick Decision Map)

- Common Mistakes That Tank Recovery Odds

- Real-World Recovery “Experiences” and Lessons From the Field (Extra Notes)

- Experience #1: “I deleted it five minutes ago” (the best-case panic)

- Experience #2: “I emptied the Trash” (the emotional plot twist)

- Experience #3: “I reformatted the USB drive by accident” (the classic)

- Experience #4: “The USB stick is acting weird or disconnecting” (hardware drama)

- Experience #5: “I only need one specific file” (the laser-focused mission)

- Experience #6: “I recovered 20,000 files and none have names” (welcome to carving)

- Conclusion

You know that split-second when you meant to delete one file, but your finger did interpretive dance on the keyboard and your entire folder disappeared?

Yeah. That moment. If your missing files lived on a USB pen drive, Linux can absolutely helpif you act fast and do the right kind of “panic.”

(Pro tip: the right kind of panic involves not writing more data to the drive.)

This guide walks you through eight practical ways to recover deleted files from a pen drive in Linux, from the easy “check the Trash” win

to forensic-grade recovery from a disk image. It’s written for normal humans, but it’s detailed enough that you won’t feel like you’re reading fortune cookies.

First Aid: What to Do Immediately (Before You Make It Worse)

File recovery is like rescuing a sandwich you dropped: the longer it sits, the more questionable your odds. On a USB drive, “deleted” usually means

“the file system forgot where it is,” not “the bytes evaporated.” But the next write operation can overwrite those bytes. So:

- Stop using the pen drive immediately. No copying, no downloading, no “just checking one thing.”

- Unmount it (so your desktop environment doesn’t write metadata behind your back).

- Work from an image whenever possible (safest and most repeatable).

Identify the USB device

Unmount the USB partition

Example: if your USB partition shows up as /dev/sdb1:

Optional but smart: remount read-only (for inspection)

Now that you’ve stabilized the patient, let’s talk recovery methods. Which one is “best” depends on the file system (FAT32/exFAT/NTFS/ext4),

whether you emptied the Trash, and whether anything new was written since deletion.

1) Check the Linux Trash on the Pen Drive (Yes, It Might Be That Simple)

If you deleted files using a graphical file manager (GNOME Files, KDE Dolphin, etc.), your files might not be truly deleted.

They may have been moved into a hidden Trash folder on the pen drive itself. On removable media, you’ll commonly see folders like:

.Trash-1000(the number often matches your user ID).Trash(less common, depends on permissions and file system behavior)

How to look for trashed files

If you find your files there, congratulationsyou just solved a crisis with the digital equivalent of checking the couch cushions.

Copy the files off the USB drive to a safe location (your internal disk).

2) Restore from Backups, Sync, or “Past You Was Smarter Than Present You”

This is not the most exciting method, but it’s often the most successful. If the deleted files were ever copied to a laptop, cloud storage,

email attachment, or a project folder synced somewhere, recovery might be as simple as pulling them back from:

- Cloud sync folders (Google Drive/Dropbox/OneDrive equivalents on Linux)

- Versioned backups (TimeShift snapshots, rsync rotations, restic/borg archives)

- Old exports (zips you sent to a coworker, a shared folder you forgot exists)

Why mention this in a “recover deleted files from pen drive in Linux” article? Because file recovery tools can be surgical… or they can be messy.

Backups preserve names, folders, and timestamps. Carving tools often give you f123456789.jpg and a deep sense of existential dread.

3) Make a Disk Image First (The Golden Rule of USB Data Recovery)

If you want the highest success rateand the lowest chance of accidentally overwriting recoverable datacreate a sector-by-sector image of the pen drive.

Then perform recovery on the image file, not the physical USB.

Simple imaging (healthy drive)

Safer imaging (failing drive): GNU ddrescue

If the drive is throwing I/O errors, making weird clicking sounds (less common on USB sticks, more common on external HDDs),

or randomly disconnecting, use ddrescue. It’s designed to copy the good parts first and keep a log so you can resume.

Once you have usb-stick.img, you can run tools against it repeatedly without risking the original media.

This is the closest thing data recovery has to “save points.”

4) Use TestDisk to Undelete Files (Best When You Want Filenames Back)

TestDisk is a classic recovery tool that can undelete files on several file systems (including FAT variants, exFAT, NTFS, and some ext formats).

When it works, it can often recover files with their original names and folder structurehuge win for sanity.

Install and run

Recommended workflow

- Select the disk image (

usb-stick.img) if you made one (recommended). - Choose the correct partition table type (TestDisk often guesses correctly).

- Use Advanced → select the partition → Undelete.

- Mark files to copy out to a different drive (never recover onto the same USB stick).

If TestDisk doesn’t find what you need, don’t quitswitch to file carving with PhotoRec (next method).

Think of TestDisk as “recover with file system knowledge,” and PhotoRec as “I don’t care what the file system thinks, I’m reading the raw data.”

5) Use PhotoRec for File Carving (When the File System Is Toast)

PhotoRec is part of the same toolkit family as TestDisk, but it’s a different beast: it ignores the file system and scans for known file signatures.

This makes it powerful for USB recovery after formatting, corruption, or serious file system damage.

The tradeoff: carving often loses original filenames and directories. You may recover lots of files, but organization becomes “good luck, hero.”

Run PhotoRec

Tips for better results

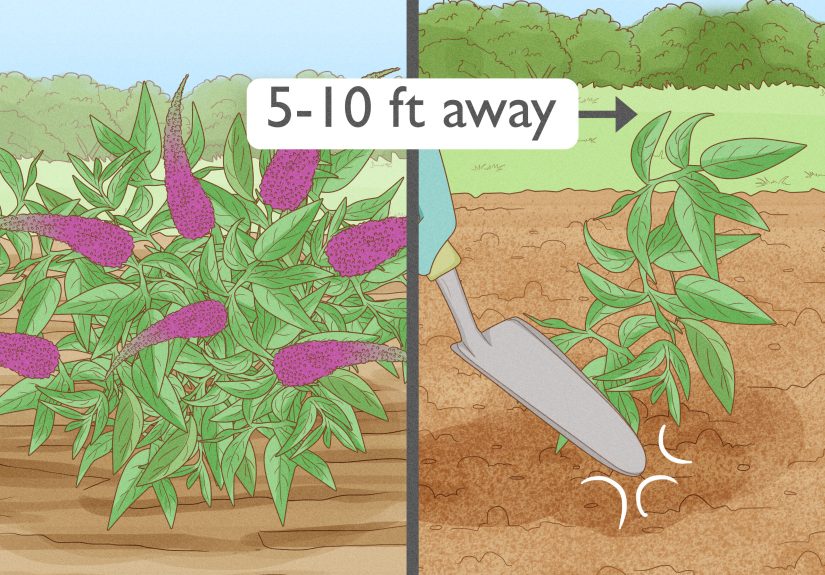

- Recover to a separate disk (your internal drive), never the same pen drive.

- Limit file types if you know what you’re hunting (e.g., only PDF/DOCX/JPG) to reduce noise.

- If you’re recovering photos, expect many duplicates and thumbnailsthis is normal.

Example: recover only documents and photos

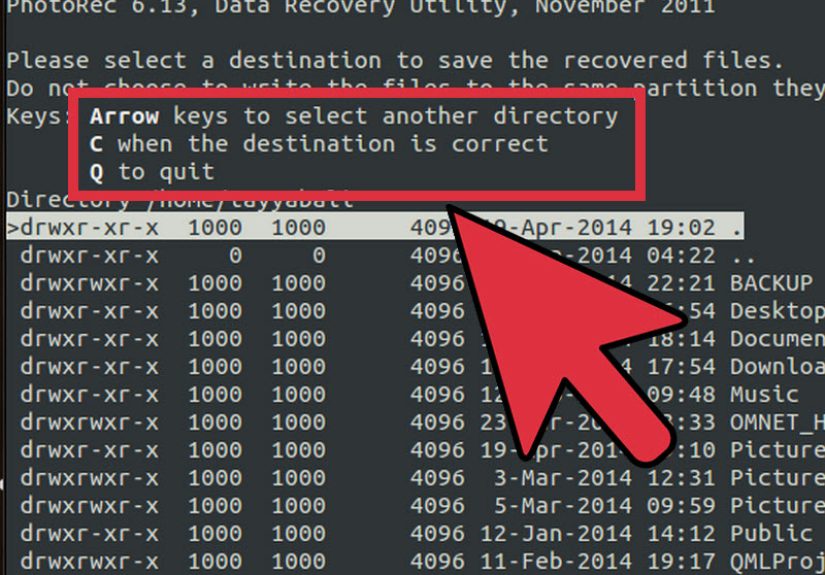

PhotoRec is interactive, but you’ll typically select the partition/image, choose “File Opt,” enable only the file types you want, then start scanning.

6) extundelete (ext3/ext4 Only): Journal-Based Undelete on Linux File Systems

If your pen drive is formatted as ext3 or ext4, you may be able to undelete using extundelete.

It attempts recovery using information in the file system journal, so the odds are best when:

- The partition was unmounted quickly after deletion

- Not much has been written since the deletion

- The journal still contains useful metadata about the deleted file

Install extundelete

Important: unmount before running extundelete

Restore everything (common approach)

Restore a specific file (if you know the path)

Recovered files typically land in a directory like RECOVERED_FILES in your current working directory.

Create a dedicated recovery folder on your internal drive before running, so you don’t scatter fragments all over your home directory like digital confetti.

7) ntfsundelete for NTFS USB Drives (If Your Pen Drive Was Used With Windows)

Many pen drives are formatted as NTFS for Windows compatibility, large file support, or pure habit.

On Linux, ntfsundelete can scan for deleted entries and attempt to recover them.

Install (package names vary by distro)

On many systems, ntfsundelete is included with NTFS utilities. If your distro splits packages, you may need an additional “ntfsprogs”/utilities package.

Scan the NTFS partition

Recover by inode (example pattern)

Practical note: NTFS recovery quality varies. If ntfsundelete can’t reconstruct your file cleanly, switch to TestDisk or PhotoRec.

They may recover more data even if names are lost.

8) Foremost/Scalpel and Sleuth Kit: Forensic-Style Recovery When You Need Options

When mainstream recovery tools don’t give you what you needor you want more controlLinux has a set of forensic utilities

that can dig into disk images and unallocated space. These are especially useful if you already created usb-stick.img.

A) Foremost (signature-based carving with a simple workflow)

Foremost carves files by signatures (similar spirit to PhotoRec, but different rules and output).

It’s useful when you want quick carving for specific file types and a predictable output directory structure.

You’ll get an output folder with subdirectories by file type. Expect some partial files and duplicatesthat’s file carving life.

B) Sleuth Kit (metadata-based recovery from disk images)

The Sleuth Kit is a well-known forensic toolkit. It can list deleted entries and, in some cases, extract content by inode.

This is more advanced, but it’s powerful when you want visibility into what the file system still “remembers.”

If you identify a promising inode, you can attempt extraction (exact syntax depends on file system type and offsets).

This is where having an image (and keeping notes) pays off.

C) When to call in professional recovery

If the pen drive is physically failing, repeatedly disconnecting, or showing as 0 bytes, your best move may be:

stop powering it up and consult a reputable data recovery service.

Flash memory failures can be complex due to controllers and wear-leveling. Software can’t always fix hardware reality.

How to Choose the Right Method (Quick Decision Map)

- Deleted via file manager? Check

.Trash-1000first. - Need filenames and folders back? Try TestDisk undelete.

- File system is corrupted or formatted? PhotoRec (and/or Foremost) carving.

- ext4 drive and you acted fast? extundelete may work well.

- NTFS drive? ntfsundelete + TestDisk are your main plays.

- Drive is failing? Image it with ddrescue before anything else.

Common Mistakes That Tank Recovery Odds

- Recovering onto the same USB drive. That can overwrite what you’re trying to recover.

- Keeping the drive mounted. Background writes (indexes, thumbnails, journal updates) can happen.

- Running random “repair” tools first. Some repairs rewrite metadata. Image first; experiment second.

- Expecting perfect results from file carving. Carving is a blunt instrumentuse it when needed, not by default.

Real-World Recovery “Experiences” and Lessons From the Field (Extra Notes)

Let’s talk about what recovery looks like in the real worldwhere file systems are messy, USB sticks are moody, and people

only start caring about backups after their files do a vanishing act. These are common scenarios and what tends to work

best, written like field notes so you can recognize your situation quickly.

Experience #1: “I deleted it five minutes ago” (the best-case panic)

If you truly deleted the file moments ago and immediately stopped using the pen drive, your odds are surprisingly goodespecially on FAT32/exFAT/NTFS.

In this situation, checking .Trash-1000 can be an instant win if the deletion happened through a GUI file manager.

If it was a terminal rm situation (a.k.a. “the command line giveth and the command line taketh away”),

TestDisk is often the next best step because it may restore the original filename. The big lesson:

time matters, but writes matter more. Five minutes with zero writes is better than thirty seconds followed by copying a movie onto the drive.

Experience #2: “I emptied the Trash” (the emotional plot twist)

Emptying the Trash doesn’t necessarily erase bytes immediately; it usually removes directory references. But it does increase the chance that your desktop

environment wrote extra metadata during deletion. In practice, if you’ve emptied the Trash, jump straight to imaging the drive and run TestDisk/PhotoRec

against the image. This is also where people discover an important truth: file carving recovers content, not memories. You’ll get files back,

but you may need to sort them manuallyespecially photos, where you’ll find everything from your vacation shots to seventeen blurry thumbnails of a receipt

from 2019.

Experience #3: “I reformatted the USB drive by accident” (the classic)

Formatting is not always a death sentence. Quick formats often rebuild file system structures without overwriting all data blocks.

PhotoRec can still carve a lot of content from a reformatted pen drive because it searches for signatures in raw space.

The key move here is psychological: don’t waste time trying ten random “repair” commands first. Create an image, carve from that,

and be prepared for renamed files. If you’re recovering documents, a helpful trick is to sort recovered output by size and file type,

then open likely candidates and “Save As” with meaningful names. It’s tedious, but it works.

Experience #4: “The USB stick is acting weird or disconnecting” (hardware drama)

When a USB drive starts disconnecting, showing I/O errors, or mounting inconsistently, you’re no longer doing normal file recoveryyou’re doing triage.

This is where ddrescue shines because it can make repeated, logged passes and salvage readable sectors first. The practical lesson:

don’t run heavy scans directly on a failing device. A deep PhotoRec scan can stress the drive, causing it to degrade faster mid-recovery.

Clone first. Scan the clone. Save the original from further suffering.

Experience #5: “I only need one specific file” (the laser-focused mission)

If you only need one filesay a PDF contract or a single folder of photosyour strategy should minimize noise.

TestDisk undelete is ideal when it can find the file by name. If you must carve, configure PhotoRec (or Foremost) to recover only the relevant file types.

This reduces the output flood and makes validation easier. Also, for office documents, check for partial corruption:

a recovered DOCX might open but have missing embedded images, and a recovered PDF might open with blank pages if parts were overwritten.

Always verify recovered files by opening them, not just trusting the extension.

Experience #6: “I recovered 20,000 files and none have names” (welcome to carving)

This is the most common outcome from carving toolsand it’s not failure, it’s the tradeoff.

A practical workflow is to: (1) sort by file type, (2) sort by size (bigger files often matter more),

(3) use previews where possible, and (4) restore meaningful naming gradually.

For photos, EXIF metadata can help you sort by date/time and camera model; for videos, duration and resolution can narrow candidates.

The lesson: carving is a firehose, so bring bucketsfilters, sorting, and a plan.

The big takeaway from all these scenarios is simple: recovery is easiest when you preserve the original state.

Unmount quickly. Image early. Recover to a different disk. And once you’re done, consider setting up a basic backup routinebecause

repeating this adventure builds character, but not necessarily joy.

Conclusion

Recovering deleted files from a pen drive in Linux is absolutely doableoften with free tools you can install in minutes.

Start with the low-hanging fruit (Trash and backups), then graduate to safer, higher-success workflows:

image the drive, attempt TestDisk undelete for filename-friendly recovery, and use PhotoRec/Foremost carving when the file system can’t help.

If hardware problems appear, ddrescue-first is the difference between “I got my data back” and “I made it worse.”