Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Freezing Water’s Electrons” Actually Means

- The Tool Behind the Magic: Attosecond Pump–Probe X-Ray Spectroscopy

- So What Did They Actually See in Water?

- The Surprise Plot Twist: A Long-Running Water Debate Gets Clearer

- Why Water Was the Perfect (and Brutal) Test Case

- Why This Matters Outside of “Water Nerd” Circles

- How the “Freeze-Frame” Works (Without Freezing Anything)

- What Comes Next: From Pure Water to Real-World Liquids

- Quick FAQs (Because Your Brain Deserves a Break)

- Conclusion: The First Frame Changes the Whole Movie

- Experiences From the Attosecond Edge (A 500-Word Add-On)

If you’ve ever tried to photograph a hummingbird’s wings, you already understand the vibe of this breakthrough.

You don’t “stop” the birdyou use a shutter fast enough that the blur vanishes and the motion looks like stillness.

Now swap the hummingbird for liquid water, and swap the camera shutter for an X-ray “strobe” that flashes in

attoseconds (that’s a billionth of a billionth of a second). The result: scientists effectively took a

freeze-frame of water’s electronic response to X-rayscapturing electrons in the act before the heavier atoms

(especially hydrogen) had time to budge.

The headline sounds like science fiction“freezing water’s electrons in time”but the story is even better: it’s

a new way to watch the very first instant of radiation-driven chemistry in liquids. And along the way, it helped

clarify a long-running debate about what certain famous water spectra are actually telling us. In other words,

researchers didn’t just get a prettier picture; they got a cleaner truth.

What “Freezing Water’s Electrons” Actually Means

Let’s get one thing out of the way: nobody put a glass of water in a cosmic freezer and told the electrons to

hold still for the camera. Electrons are quantum objects; they’re not tiny marbles you can freeze mid-roll.

What scientists can do, however, is measure electronic motion on a timescale so short that the nuclei (the

oxygen and hydrogen atoms) are effectively frozen in place during the measurement.

Why does that matter? Because most chemistry is a two-part dance:

- Electrons move first (ultrafast), reshaping bonds and energy landscapes.

- Nuclei follow (slower), as atoms shift positions, bonds stretch, and molecules rearrange.

In liquid water, hydrogen atoms are lightweight and lively, which means the molecular framework can blur fast.

Traditional X-ray techniques may “see” a mixture of electronic structure and nuclear motion. The new trick is to

interrogate water so quickly that the nuclear motion can’t smear the signalgiving a snapshot that’s dominated

by electronic response, not atomic reshuffling.

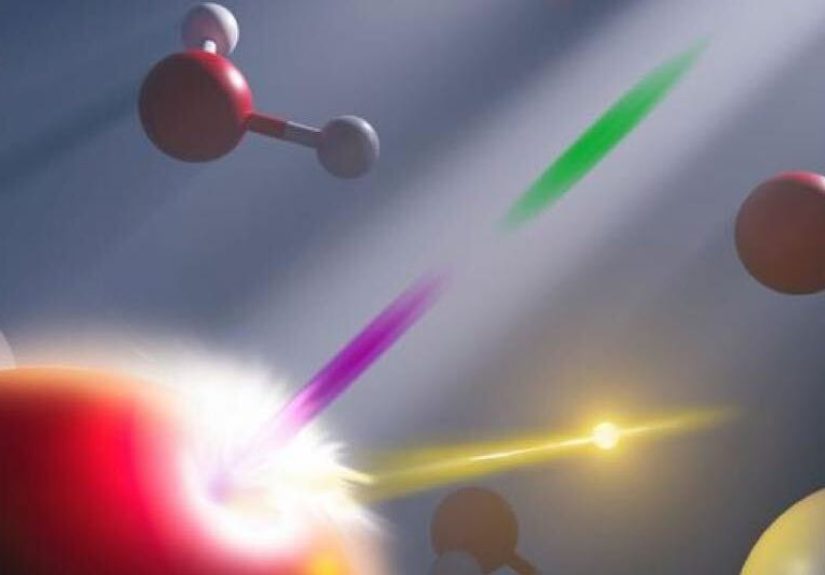

The Tool Behind the Magic: Attosecond Pump–Probe X-Ray Spectroscopy

The feat comes from a method called all X-ray attosecond transient absorption spectroscopy

(often shortened to AX-ATAS). The idea is elegantly simple and brutally hard to execute:

hit the sample with one X-ray pulse (the “pump”) and then, after a controllable delay, hit it with a second

X-ray pulse (the “probe”). By scanning the delay and reading the absorption changes, you infer how the system

evolves in time.

For this water experiment, researchers used an X-ray free-electron laser facility (the Linac Coherent Light Source,

or LCLS, at SLAC) capable of producing synchronized attosecond pulse pairs. They shaped the experiment so one pulse

ionized the valence electronic structure and the second pulse interrogated how the electronic landscape changedbefore

the nuclei could noticeably move. A key practical detail: the X-rays were focused onto a thin, flat sheet of liquid

water, which lets you do ultrafast measurements on a liquid without turning your experiment into “steam, now in 4K.”

Why Attoseconds Are the Right “Shutter Speed”

An attosecond is so small that it’s hard to picture without silly comparisons (and science loves silly comparisons).

One popular way to convey it: there are more attoseconds in a second than there have been seconds over

cosmic history. The point isn’t the triviait’s that electrons naturally move on these timescales. If you want to

see the opening frame of radiation chemistry, you need a shutter speed that doesn’t blink.

So What Did They Actually See in Water?

Water’s electronic structure isn’t just academic; it’s the scaffolding for hydrogen bonding, solvation, acidity,

and much of the chemistry that makes life and technology possible. When an X-ray interacts with water, it can kick

electrons around in ways that seed cascades of reactionssome helpful (certain medical treatments), some harmful

(radiation damage), and some complicated (nuclear waste chemistry).

With AX-ATAS, scientists observed the immediate electronic response of liquid water to X-ray

ionization on sub-femtosecond timescales. Because the snapshot happens before nuclear motion, the spectrum can be

modeled using a “fixed nuclei” picturemeaning the atoms are treated as stationary while the electronic rearrangement

is analyzed. That’s not a lazy assumption; it’s the whole point of the measurement.

The work also demanded heavyweight theory and computation to interpret what the detector sees. Attosecond snapshots

can probe many quantum states at once, and the signal can look “convoluted” without advanced modeling. The outcome:

a more direct view of how water’s electrons respond in the first instant after being hit with ionizing radiation.

The Surprise Plot Twist: A Long-Running Water Debate Gets Clearer

Here’s where the story gets deliciously scientific: the experiment wasn’t just a flex of timing controlit also

helped address how to interpret a classic spectral feature in water.

For years, researchers have debated whether certain “split” signals in water’s X-ray spectra point to different

structural motifs (think: two kinds of local water arrangements coexisting) or whether those splits arise from

hydrogen-atom dynamics that occur during the measurement itself.

Attosecond pump–probe measurements can slice through that ambiguity because they operate on a timescale too fast for

the hydrogen atoms to rearrange significantly. In this picture, if a spectral splitting disappears in the attosecond

snapshot, it suggests the splitting is driven more by dynamics (atoms moving during the process) than by a static

mixture of structures present at equilibrium.

In accessible terms: the new technique can reduce “motion blur.” And once you remove motion blur, you can stop

mistaking blur artifacts for hidden objects in the scene.

Why Water Was the Perfect (and Brutal) Test Case

Water is famous for being ordinary and weird at the same time. It’s everywhere, yet it refuses to behave like most

liquids. Its hydrogen bonds form and break constantly, its local structure is endlessly debated, and its response to

radiation underpins real-world problems from biology to energy.

That makes water an ideal proving ground for a method meant to study radiation-driven chemistry in liquids. If your

technique can handle waterwhere everything jiggles, bonds flicker, and signals broadenthen you’ve built something

sturdy enough to tackle more complex mixtures next.

Why This Matters Outside of “Water Nerd” Circles

The practical value of freezing an ultrafast electronic moment is that radiation-induced processes often begin with

electrons moving first, then chemistry snowballing from there. If you can resolve the earliest electronic steps,

you can build better models of what happens next.

1) Radiation chemistry and nuclear waste

In nuclear waste environments, radiation continuously generates reactive species in complex aqueous mixtures. The

earliest electronic response can influence which radicals form, how fast they form, and what reaction pathways are

even possible. A technique that targets the “first frame” can help improve mechanistic understandingand, over time,

guide safer handling and more effective mitigation strategies.

2) Medicine and radiation damage

Many radiation effects in biological systems are mediated by water because cells are mostly water. Ionizing radiation

triggers electronic events that can lead to harmful chemistry (like damaging DNA indirectly via reactive species).

Better insight into the initial electronic response in water is one ingredient in a larger recipe for understanding

and potentially controlling downstream damage.

3) Space, reactors, and any place where radiation meets liquids

From space travel to reactor coolant systems, the interaction of radiation with liquids and solvated species can

influence material degradation, chemical byproducts, and long-term stability. Seeing the start of the chain reaction

matters when the chain reaction runs your world.

How the “Freeze-Frame” Works (Without Freezing Anything)

The freeze-frame is really about timing and selectivity:

- Timing: Use pulse pairs separated by hundreds of attoseconds to capture changes before atoms move.

- Selectivity: Use X-ray absorption changes to read out which electronic states are involved right after ionization.

- Modeling: Interpret the spectrum with theory that treats nuclei as fixed during the ultrafast window.

In everyday language: the method doesn’t stop the danceit takes a photo before the dancers’ feet have time to shift.

What Comes Next: From Pure Water to Real-World Liquids

The water result is a beginning, not an ending. Researchers anticipate extending attosecond X-ray approaches to more

complex aqueous systems: dissolved ions, radiation-relevant chemicals, and mixtures that better reflect “messy reality.”

One enticing direction is tracking the birth and evolution of reactive intermediates produced by

radiationshort-lived species that are hard to catch but crucial for understanding chemical outcomes. Another is using

ultrafast data to refine how we interpret traditional X-ray spectra in liquids, separating what’s structural from

what’s dynamical.

Quick FAQs (Because Your Brain Deserves a Break)

Did scientists literally freeze electrons?

No. They measured electronic response on such a short timescale that atomic motion is effectively frozen during the

measurement window.

Is this about freezing water into ice?

Also no. The “freeze” is metaphoricalabout time resolution, not temperature.

Why are two pulses better than one?

The first pulse initiates the change (ionization/excitation). The second pulse probes what changed. By controlling

the delay, you reconstruct the earliest evolution.

Why do they need giant facilities?

Producing intense, synchronized attosecond X-ray pulses is extremely challenging. X-ray free-electron lasers can

deliver the brightness and timing control needed for this class of experiment.

Conclusion: The First Frame Changes the Whole Movie

“Freezing water’s electrons in time” is a poetic way to describe a very concrete achievement: using synchronized

attosecond X-ray pulse pairs to capture the earliest electronic response in liquid water before nuclear motion blurs

the picture. Beyond the wow factor, the method strengthens how scientists interpret water’s X-ray spectra and opens a

new path for studying radiation-driven chemistry in liquidswhere the most important events happen long before a

conventional stopwatch even notices the start.

The big takeaway is simple: when you can finally see the first instant clearly, you stop arguing about shadows and

start learning what’s actually there. And for a substance as deceptively complicated as water, that’s not just

progressit’s relief.

Experiences From the Attosecond Edge (A 500-Word Add-On)

If you ever talk to people who run ultrafast experiments on liquids, you’ll notice a shared expression: part pride,

part fatigue, part “I can’t believe the universe agreed to be measured today.” Beamtime at an X-ray free-electron

laser tends to feel like a scientific road trip where the destination is a number so small it barely fits on the

page. The “freezing electrons in time” story sounds smooth in headlines, but the lived experience is more like

juggling bowling pins while riding a unicycleon a schedule.

One common experience is the obsession with alignment. The water isn’t sitting politely in a cuvette;

it’s often delivered as a thin, fast-moving sheet or jet that has to be stable enough for X-rays to hit the target

the same way over and over. Researchers talk about tiny adjustmentsmicrons here, fractions of a degree therethat

decide whether you collect a clean signal or a modern-art masterpiece titled “Noise, With Notes of Despair.”

Then there’s timing, the diva of the entire production. Pump–probe science lives and dies by how well

you control and measure delay between pulses. When delays are in the hundreds of attoseconds, the experiment becomes

a masterclass in humility: you’re not just measuring water, you’re negotiating with it, with the laser, with the

accelerator, and with physics itself. People describe the moment they first see a stable time-dependent feature as

pure adrenalinefollowed immediately by the thought, “Okay, now we have to explain what it means.”

Data handling is another shared experience. Attosecond experiments can generate a flood of measurements quickly, and

the raw output rarely arrives with a helpful sticky note saying “This is the answer.” Teams often spend nights

scanning through plots, checking instrument diagnostics, and verifying that what they see is realbecause at this

scale, artifacts can cosplay as discoveries. When a signal looks “convoluted,” that’s not a polite inconvenience;

it’s a full-on invitation to invent better analysis tools and stronger theoretical models.

Collaboration becomes less of a buzzword and more of a survival strategy. A typical campaign blends accelerator

physicists who can coax the machine into delivering exquisite pulses, experimentalists who know how to keep a liquid

target behaving in vacuum, and theorists/computational chemists who translate spectra into physical meaning. Many

researchers describe the best days as the ones where everyone’s expertise overlaps just enough to push the project

through the narrow gate between “impossible” and “done.”

And finally, there’s the emotional experiencethe oddly human thrill of watching a fundamental process unfold in a

new way. Water is ordinary until you zoom in far enough, fast enough. Then it becomes a universe of motion, and

that “freeze-frame” is a reminder that scientific progress isn’t always about building bigger theories. Sometimes

it’s about building a better shutter, taking one impossibly fast picture, and letting reality speak for itself.