Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The #1 Drone Problem Isn’t Always Battery Life. It’s the Noise

- Leonardo’s “Aerial Screw”: A Helicopter Idea Before Helicopters Existed

- What Modern Researchers Found When They Tested the Aerial Screw

- How a Da Vinci-Inspired Rotor Could Help Real-World Drone Missions

- The Tradeoffs: Why You Don’t Already Own a Da Vinci Drone

- This Isn’t the Only Quiet-Drone IdeaAnd That’s a Good Thing

- So… Will This Actually “Fix” Drone Noise?

- What Drone Operators Can Do Right Now to Reduce Noise

- Experience Section: What “Quiet Drones” Would Change in Real Life (500+ Words)

- Conclusion

Drones are amazing at the “wow” stuff: cinematic aerial shots, bridge inspections, farm mapping, even dropping off urgent supplies.

And yet, the moment one shows up over a neighborhood, the vibe can shift from future-forward to why is a swarm of angry kazoos hovering above my house?

That high-pitched buzzing isn’t just annoyingit’s one of the biggest barriers to wider drone adoption in everyday life.

If people hate the sound, they’ll fight the rules, the routes, the permits, and the whole idea of drones being “normal.”

Which is why a 500-ish-year-old concept from Leonardo da Vinciyes, the Renaissance guy with the notebookshas engineers taking a serious second look.

The #1 Drone Problem Isn’t Always Battery Life. It’s the Noise

Ask drone pilots what limits their flights and you’ll hear: battery life, wind, range, and regulations.

Ask the public what they notice first and you’ll get a simpler answer: the sound.

Small multirotor drones produce a distinctive, high-frequency, tonal “whine” that can feel intrusiveespecially in quiet places like parks,

suburbs, and backyards where nobody ordered an overhead remix.

Noise matters because it shapes acceptance. If communities don’t tolerate drone noise, commercial use casesdelivery, infrastructure inspection,

public safety supportface friction before they even take off. Regulators and researchers also treat noise as a major community-impact issue,

and agencies like the FAA and NASA have ongoing work focused on measuring and reducing rotor and propeller noise.

In other words: drones don’t just need to fly better. They need to sound better.

Leonardo’s “Aerial Screw”: A Helicopter Idea Before Helicopters Existed

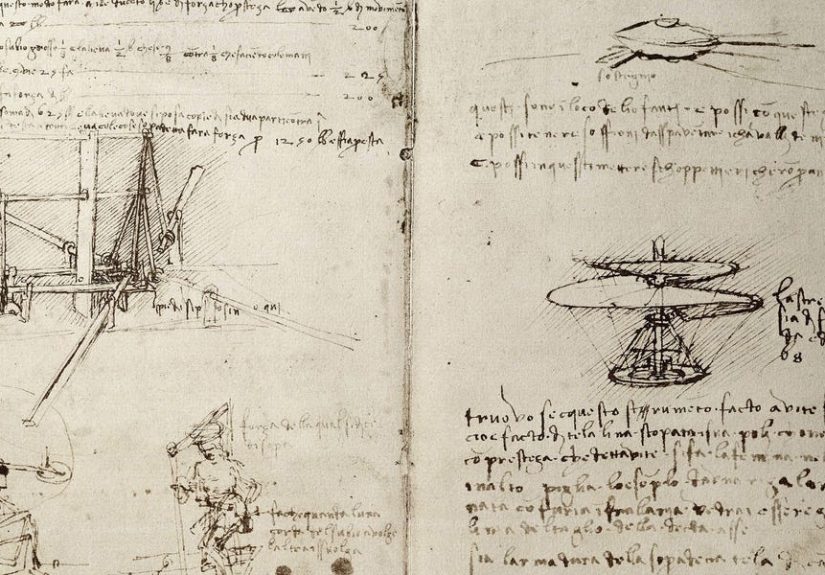

In the late 1400s, Leonardo da Vinci sketched a strange flying machine that looks like a spiral ramp wrapped around a pole.

It’s often called the aerial screwa helical rotor meant to push air downward as it spins, generating lift.

Think of it like an “Archimedes’ screw,” except instead of lifting water, it tries to persuade air to cooperate.

Leonardo didn’t have lightweight motors, modern composites, or high-energy batteries. His concept was centuries early.

A human-powered spiral of heavy materials isn’t exactly the recipe for smooth vertical takeoff. So the aerial screw became famous mostly as a

brilliant “what if.”

But modern engineers love a good “what if,” especially when computers can test it without anyone having to pedal a helicopter like a stationary bike.

What Modern Researchers Found When They Tested the Aerial Screw

Recent computational studies have revisited the aerial screw using high-end simulation methods to compare it with conventional drone rotors.

The headline result: the aerial screw concept can offer meaningful noise reduction and may require less mechanical power

under certain conditionsthough it doesn’t automatically beat today’s best rotors on every performance metric.

Why might it be quieter?

Many modern drone propellers create noise through a combination of blade-vortex interactions, tip vortices, and high rotational speeds.

The aerial screw’s continuous spiral surface can spread aerodynamic loading differently than discrete blades.

If the design produces the needed lift at a lower RPM (or shifts the “annoying” frequencies),

it may reduce that sharp, mosquito-in-a-megaphone character people associate with drones.

Why might it need less power?

Power depends on how efficiently the rotor turns motor energy into thrust and lift. A continuous helical surface changes the flow pattern

and can reduce some loss mechanismsat least in the simplified comparisons researchers have run.

That doesn’t mean “free flight time forever,” but it hints at a valuable trade: quieter operation without an energy penalty that ruins usefulness.

The biggest takeaway is not that Leonardo secretly solved drone engineering in 1480.

It’s that unusual rotor geometriesespecially ones that increase effective surface area and alter vortex behaviormay offer a new path toward

drones that can operate in populated areas without sounding like a tiny leaf blower having a tantrum.

How a Da Vinci-Inspired Rotor Could Help Real-World Drone Missions

Let’s translate engineering findings into real life. If drones get quieter, several high-value uses get easier to scale:

-

Urban delivery: A quieter drone is less likely to trigger complaints, local restrictions, or negative headlines.

(Nobody wants “Delivery Drone Outrage” trending because a neighborhood sounded like a beehive convention.) - Infrastructure inspections: Utilities and city agencies can operate more frequentlyespecially early morningsif noise impact is lower.

- Public safety: Search-and-rescue or disaster response drones may be able to linger longer overhead without adding stress to an already tense situation.

- Filmmaking and events: Less prop noise means cleaner audio capture and fewer “we’ll fix it in post” prayers.

- Wildlife and environmental monitoring: Noise reduction can lower the chance of disturbing animals during surveys.

In short: quieter drones aren’t just “nice.” They’re a practical unlock for more flights, more routes, and more trust.

The Tradeoffs: Why You Don’t Already Own a Da Vinci Drone

If the aerial screw is so promising, why aren’t drones already shaped like giant fusilli?

Because engineering is the art of choosing which problems you want to fight today.

Lift and efficiency aren’t automatically better

Some comparisons show the aerial screw may generate less lift than standard rotors in certain configurations.

That can be a dealbreaker if you need to carry a payload, fight wind, or maximize hover time.

It also means the design likely needs optimizationmaterials, geometry tweaks, pitch adjustments, and possibly hybrid forms.

Manufacturing and integration challenges

A helical rotor may be harder to manufacture, balance, and protect than standard off-the-shelf props.

Drones also rely on compact, lightweight components; a bulkier rotor design can change the entire airframe layout.

Control systems and stability

Multirotor drones are popular because they’re mechanically simple and control-stable. Any new rotor geometry must work with flight controllers,

respond predictably to throttle changes, and handle gusts without turning the drone into modern art.

The good news: these are solvable problems. The “hard” part isn’t that the aerial screw is impossibleit’s that the modern drone ecosystem is

optimized around conventional propellers, and changing a core component means redesigning a lot of assumptions.

This Isn’t the Only Quiet-Drone IdeaAnd That’s a Good Thing

The da Vinci approach fits into a wider push for quieter propulsors in drones and urban air mobility. Engineers are exploring multiple strategies:

Lower RPM with more blades

One straightforward approach is using higher blade counts and operating at lower rotational speeds.

This can reduce noise, though it may come with performance tradeoffs and requires careful design to maintain efficiency.

Novel shapes like toroidal propellers

Toroidal (“donut-shaped”) propellers have been highlighted as a potential way to reduce noise while maintaining thrust.

Their geometry changes tip vortex behaviora big contributor to the irritating sound profile of small rotors.

Smarter control, not just new hardware

Noise isn’t only about shape. Flight control strategies can reduce tonal peaks, avoid operating points that create the most annoying frequencies,

and minimize sudden RPM swings that grab attention.

Put these together and you get a realistic future: drones that combine better rotor shapes, better motor control, and better operating practices.

Da Vinci’s aerial screw may become one tool in a larger “quiet skies” toolbox.

So… Will This Actually “Fix” Drone Noise?

“Fix” is a big word. Noise is part physics, part perception, and part context.

A drone that seems “fine” next to a highway can feel obnoxious over a quiet lake.

But there’s reason to take the aerial screw idea seriously:

- It targets the real pain point: the tonal, high-frequency character people dislike most.

- It suggests improvement without a huge energy penalty: crucial for electric drones.

- It expands the design space: engineers can optimize helical rotors the way modern props were optimized over decades.

The next step is moving from simulation and theory into iterative prototyping:

wind-tunnel tests, outdoor measurements, and psychoacoustic studies that evaluate not just decibels, but annoyance and sound quality.

What Drone Operators Can Do Right Now to Reduce Noise

Even before da Vinci-inspired rotors hit store shelves, practical habits can make drones less irritating:

- Fly higher when safe and legal: distance reduces perceived loudness fast.

- Avoid hovering over people’s homes: moving flights are often less annoying than stationary buzzing.

- Use smoother throttle changes: abrupt RPM jumps draw attention.

- Choose quieter prop designs: some aftermarket props emphasize lower noise profiles.

- Respect quiet hours: nobody wants sunrise drone karaoke.

Quiet isn’t just a technical spec. It’s part of being a good neighbor with a flying robot.

Experience Section: What “Quiet Drones” Would Change in Real Life (500+ Words)

The interesting thing about drone noise is that it’s not only measured in decibelsit’s measured in reactions.

Talk to people who operate drones professionally and you hear the same pattern: the mission is usually fine, the footage is great,

the data is clean… and then the sound becomes the headline in someone’s day.

A real estate photographer might describe a perfect morning shoot that gets interrupted by a neighbor stepping outside, squinting at the sky,

and asking, “How long is that thing going to be here?” Not because the drone is dangerous, but because the buzzing is impossible to ignore.

Even when the pilot is following the rules, the noise feels personallike someone left a tiny lawn tool running over your roof.

A quieter rotor changes that interaction. It doesn’t eliminate curiosity, but it reduces the “please make it stop” urgency.

Utility inspection teams have a different kind of story: they often need repeat flights along the same corridorpower lines, pipelines,

or rooftopssometimes multiple times a year. The first flight might be tolerated. The fifth one, less so.

People don’t always complain because they hate technology; they complain because the sound is a reminder that something is hovering nearby.

When noise is reduced, the operation becomes less of an “event,” and more of a background processlike a street sweeper that doesn’t wake you up.

Delivery pilots (and the planners who design routes) run into the same human reality. A drone might only pass over a house for a few seconds,

but if it produces a sharp, high-frequency tone, the brain treats it like a smoke alarm that can’t decide whether it’s serious.

That’s why the character of the sound matters as much as volume. People will tolerate a low, brief whoosh far more than a thin, sustained whine.

If a da Vinci-inspired design shifts or softens those tonal peaks, it makes the whole idea of routine delivery less socially expensive.

Then there’s the public safety angle. In search-and-rescue or emergency response, drones can help locate people, map hazards,

or provide situational awareness. But responders also work in emotionally charged environments.

A loud drone hovering overhead during a tense moment can add stress and make communication harder.

Quieter flight supports the mission without dominating the soundscape. It’s the difference between “useful tool” and “another problem to manage.”

And finally, the hobbyists. Many drone owners love the craftlearning camera moves, practicing safe flight, exploring landscapes.

But they also know the awkward feeling of launching in a park and watching heads turn.

A quieter drone doesn’t just reduce complaints; it reduces that social friction that makes people feel like they’re “doing something wrong”

even when they aren’t.

In all these scenarios, the value of quieter rotors isn’t abstract. It’s fewer confrontations, fewer restrictions,

more flexibility for legitimate work, and a better chance that drones become a normal tool instead of a neighborhood controversy.

If Leonardo’s aerial screw helps engineers get thereeven as inspiration rather than a direct copythen it’s not just a historical curiosity.

It’s a blueprint for making the future a little less noisy.

Conclusion

Leonardo da Vinci didn’t invent the modern drone, but he did something engineers still do today: he imagined a different way to solve a problem.

By revisiting the aerial screw with modern simulation and materials, researchers are discovering that “old ideas” can open new doors

especially for the biggest real-world challenge drones face in cities: noise.

Whether the future belongs to helical rotors, toroidal propellers, smarter control systems, or a hybrid of everything,

the direction is clear. The drones that win long-term won’t just be the ones that fly farther.

They’ll be the ones that can show up in everyday life without sounding like a swarm of electric wasps filing a complaint.