Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Ancient DNA 101: How Do You Read a 40,000-Year-Old Receipt?

- The 10 Remarkable Ancient DNA Discoveries

- 1. We All Have a Little Neanderthal in Us (Well, Most of Us)

- 2. Denisovans: The Ghost Cousins We Met Through a Finger Bone

- 3. Mapping the Great Human Road Trips Across the Globe

- 4. A Genetic Window Into the Indus Valley Civilization

- 5. Wolves to Best Friends: Ancient DNA and Domesticated Animals

- 6. Tracking Plague and Ancient Pandemics Through Time

- 7. A Rock Shelter That Hosted the Same People for 9,000 Years

- 8. The Routes to Australia and the Mystery of Sahul

- 9. Mammoths, Megafauna, and the Oldest Genetic Time Capsules

- 10. Bronze Age Remix: Ancient DNA Rewrites the Story of Civilizations

- Living With Ancient DNA: Reflections and Real-World Experiences

- Conclusion: The Dead Are Talking, and We’re Finally Listening

Once upon a time, if you wanted to know what happened 10,000 years ago, you had to squint at broken pottery and hope for the best.

Now scientists grab a tooth, a bone fragment, or even a chunk of mammoth jerky from Siberian ice and say, “Let’s sequence it.”

Welcome to the age of ancient DNA, where genomes have become time machines and our ancestors are frankly a lot weirder and more interesting than we expected.

In the past few decades, advances in genetics have turned archaeology into something that looks suspiciously like science fiction.

From discovering ghost populations that no longer exist to tracking pandemics across millennia, ancient DNA has quietly rewritten huge chunks of

human history, evolutionary biology, and even our understanding of disease.

Below are ten of the most remarkable discoveries that came from ancient DNA the kind of findings that make textbooks cry and history teachers completely rewrite their lectures.

Ancient DNA 101: How Do You Read a 40,000-Year-Old Receipt?

Before we dive into the list, a quick primer. Ancient DNA (aDNA) is genetic material extracted from long-dead organisms: bones, teeth, mummified tissue,

even sediments. It’s usually fragmented, chemically damaged, and contaminated with microbes and modern human DNA.

Early attempts in the 1980s were hit or miss, but with PCR amplification, clean-room techniques, and high-throughput sequencing,

scientists now routinely sequence genomes from remains tens or even hundreds of thousands of years old.

The result? A direct view into the past. Instead of guessing who lived where based on artifacts alone, we can now

track migrations, interbreeding, epidemics, domestication, and even gene activity from specific moments in time.

It’s like going from “maybe someone used this stone tool here” to “this woman had brown eyes, lived near the Black Sea, ate a lot of barley, and carried genes that protect against plague.”

The 10 Remarkable Ancient DNA Discoveries

1. We All Have a Little Neanderthal in Us (Well, Most of Us)

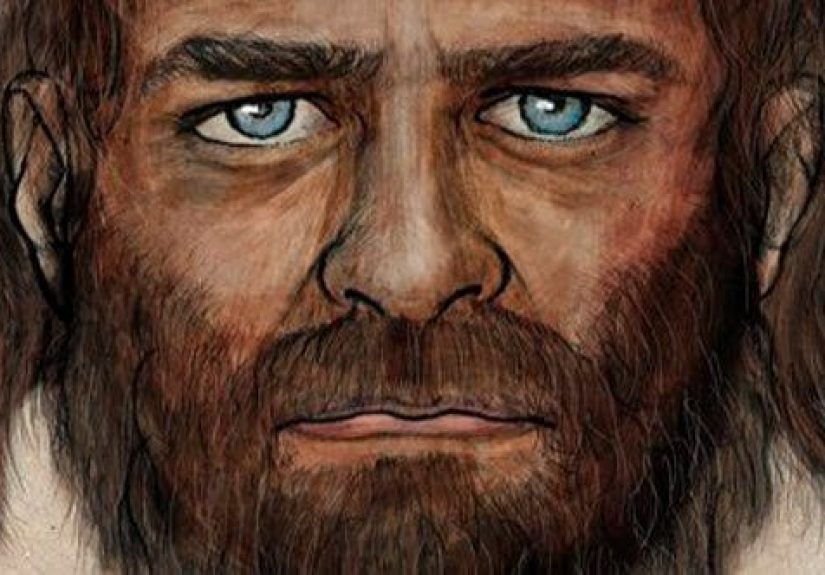

For a long time, the story went like this: modern humans left Africa, bumped into Neanderthals, and then Neanderthals died out because we were smarter, prettier, or had better sneakers.

Ancient DNA smashed that neat narrative. When researchers sequenced the Neanderthal genome, they discovered that people outside sub-Saharan Africa carry about

1–4% Neanderthal DNA in their genomes. In other words, our ancestors didn’t just meet Neanderthals they dated them.

Those Neanderthal fragments aren’t just historical souvenirs. Some are linked to how we respond to infections, our risk of depression, blood clotting, and even how we react to

air pollution and certain medications. It turns out that “modern” humans are actually mosaics of multiple ancient human lineages.

The family tree is less like a clean branching diagram and more like a tangled ball of yarn that someone’s cat got into.

2. Denisovans: The Ghost Cousins We Met Through a Finger Bone

In 2010, scientists sequenced DNA from a tiny finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia. It didn’t match modern humans. It didn’t match Neanderthals.

Congratulations, world: we had discovered a whole new group of ancient humans the Denisovans almost entirely from DNA.

Even more mind-blowing, ancient DNA later revealed an individual nicknamed “Denny,” whose mother was Neanderthal and father Denisovan

the first direct, first-generation hybrid human ever identified. Modern people in parts of Asia and Oceania still carry Denisovan ancestry,

including gene variants that help with high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. If you’re hiking in the Himalayas without gasping for air as much,

you might owe a thank-you to a Denisovan great^100-grandparent.

3. Mapping the Great Human Road Trips Across the Globe

Ancient DNA has transformed our understanding of how people spread across the planet. Instead of just relying on tools, pottery styles, or language,

scientists now directly compare ancient genomes with modern ones to reconstruct ancient migrations.

For example, genomes from individuals in Siberia, the Arctic, and North America helped trace the complex peopling of the Americas, revealing

multiple waves of migration via Beringia and later movements that shaped Arctic populations. Other studies have shown that ancestors of some

Native American groups later moved back across the Bering Sea into Asia, meaning that “out of Beringia” was not a one-way trip.

The story of human migration looks less like a single arrow on a map and more like a messy subway diagram at rush hour.

4. A Genetic Window Into the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization, contemporaneous with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, left behind impressive cities but almost no readable written records.

Ancient DNA changed that. Sequencing from rare human remains associated with this civilization has suggested that its people had a unique genetic profile,

with ancestry components still found in South Asia today.

These findings support the idea that South Asia’s population history is a complex blend of ancient local hunter-gatherers, early farmers from Iran,

and later steppe pastoralists. Instead of a single “Aryan invasion” event, ancient DNA points to multiple waves of interaction and mixing over thousands of years.

In short: the region’s genetic history is just as sophisticated and layered as its archaeology always hinted.

5. Wolves to Best Friends: Ancient DNA and Domesticated Animals

Ancient DNA doesn’t just spill secrets about humans it also reveals how we teamed up with animals.

By sequencing ancient dog and wolf genomes, scientists have traced how dogs were domesticated from wolves, probably in multiple regions and times,

before becoming humanity’s emotionally supportive vacuum cleaners.

Comparing ancient and modern genomes shows how traits like tameness, coat color, and size evolved. Similar work on cattle, pigs, and horses reveals

how domestication reshaped not only the animals but also human societies. Once you can hitch animals to plows or ride them into battle,

entire economies and empires become possible. Ancient DNA is effectively showing us the genetic blueprints behind the invention of “pets,” “farms,” and “civilization as we know it.”

6. Tracking Plague and Ancient Pandemics Through Time

Historians have long debated which diseases caused famous pandemics, especially the Black Death and earlier mysterious plagues.

Ancient DNA stepped in, shrugged, and said, “Let me check.” By pulling DNA from teeth in medieval and ancient burials,

scientists identified the pathogen Yersinia pestis the bacterium that causes plague in victims from multiple pandemics separated by centuries.

More recent work has mapped the genetic history of hundreds of pathogens over tens of thousands of years, revealing how the rise of farming and animal domestication

changed our disease landscape. As humans started living densely with livestock, we created the perfect environment for infectious diseases to jump, evolve, and spread.

Ancient DNA can even trace how certain immune system genes spread through human populations in response to these long-ago outbreaks.

In other words, your immune system is partly a historical document of epidemics your ancestors survived.

7. A Rock Shelter That Hosted the Same People for 9,000 Years

At a rock shelter in southern Africa, archaeologists uncovered human remains spanning thousands of years.

Ancient DNA from these skeletons revealed something remarkable: genetic continuity over roughly 9,000 years.

The same population genetically speaking appears to have lived in and around that shelter for millennia.

Even more striking, other research on ancient genomes from southern Africa has uncovered a deeply divergent branch of human ancestry,

one that sits at the far edge of known modern human genetic variation. These findings highlight that Africa’s genetic history is extraordinarily rich and regionally diverse,

and that many lineages that contributed to today’s populations are only now being recognized.

It’s a powerful reminder that “out of Africa” is only one small piece of a much larger African story.

8. The Routes to Australia and the Mystery of Sahul

The peopling of Sahul the ancient landmass that once connected Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania has been a long-standing puzzle.

With limited archaeological sites and challenging geography, researchers argued over whether people arrived via a northern route, a southern route, or some combination.

Modern and ancient genomic data now suggest that both coastal and inland routes were likely used, and that distinct groups contributed ancestry to Indigenous Australians

and Papuans at different times. While ancient DNA from Sahul itself is still rare, the genetic signal in living populations and a handful of ancient remains

has given us our clearest look yet at one of humanity’s most epic sea-crossing migrations.

9. Mammoths, Megafauna, and the Oldest Genetic Time Capsules

Humans aren’t the only stars of the ancient DNA show. Scientists have sequenced genomes from extinct megafauna like woolly mammoths,

revealing details about their population structure, adaptations to cold, and eventual decline.

One especially famous specimen, preserved in Siberian permafrost, has yielded not only DNA but even ancient RNA,

pushing the limits of how far back molecular biology can peek.

These data show how climate shifts and human hunting likely worked together to push mammoths toward extinction.

They also provide a test bed for controversial ideas like “de-extinction,” where researchers explore whether traits from extinct species might one day be reintroduced into

their closest living relatives. Whether or not we ever see a “mammophant” strolling around, ancient DNA has already given mammoths a second life in the lab.

10. Bronze Age Remix: Ancient DNA Rewrites the Story of Civilizations

Ancient DNA has also reshaped our view of the Bronze Age, revealing that many regions once assumed to be stable and isolated

actually saw large-scale movements of people. Studies in the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, for instance, show complex mixtures of local populations

with migrants from Anatolia, the Caucasus, and the Eurasian steppe.

These findings complicate older narratives that focused only on invading armies or cultural diffusion through trade.

Instead, genetic data show that real human bodies moved sometimes in waves linked to climate change, collapse of empires, or technological shifts like new metalworking techniques.

The result is a far more dynamic picture of the ancient world, where cultures rose and fell alongside deep genetic reshufflings.

Living With Ancient DNA: Reflections and Real-World Experiences

So what does all this mean for ordinary people who are not currently sequencing mammoth toenails for a living?

The impact of ancient DNA has quietly seeped into everyday life in ways that range from fun to profound.

First, there’s the boom in consumer ancestry testing. While those tests mainly use modern DNA, the reference panels and models behind them are heavily informed by

ancient DNA research. The idea that your genome can be broken down into “percentages” of different ancestries

say, Scandinavian, West African, or Indigenous American only makes sense because scientists have spent years mapping how populations formed, split, and mixed over deep time.

When you get a surprise result (“Wait, why do I have ancestry from Siberia?”), that story is often tied to real ancient migrations revealed by ancient genomes.

On a more personal level, ancient DNA can change how people relate to history. Visiting a museum feels different when you know that the skeleton in the glass case once carried

some of the same immune system variants you do, or that the people who built a long-vanished city are still genetically present in modern populations.

History stops being an abstract list of dates and becomes a family drama messy, complicated, and full of long-lost cousins.

For researchers, working with ancient DNA is both exhilarating and humbling. Extracting genetic material from fragile bones or teeth is a painstaking process:

full-body suits, filtered air, and an obsessive fear of contamination from your own cells. A single misguided sneeze can ruin a sample that has waited 5,000 years

for its moment in the spotlight. Yet when the data finally emerge, they can overturn decades of careful theorizing.

Archaeologists and geneticists now collaborate closely, constantly negotiating between what the bones say and what the genomes insist.

There are also ethical questions. Ancient DNA doesn’t just belong to scientists; it’s part of the heritage of living communities.

Many Indigenous groups are increasingly involved in decisions about whether remains are sampled, how data are used, and how findings are communicated.

Some communities welcome the additional layer of history; others are understandably wary of having their ancestors turned into datasets or used to justify political narratives.

A responsible ancient DNA project today tends to include long-term partnerships, consultation, and respect for cultural protocols not just fancy sequencing machines.

On a broader cultural level, ancient DNA can be both comforting and destabilizing. It undermines simple stories: there is no pure lineage, no unbroken bloodline,

no group that has “always” lived in exactly the same place. Everyone is mixed. Everyone has moved.

For some people, that’s a thrilling realization we’re all part of one sprawling, tangled human family.

For others, it challenges identities built on tidy origin stories.

And then there’s the sheer wonder. Somewhere in a frozen cave, a finger bone the size of a peanut quietly held the secret of an entire lost group of humans.

A tooth from a medieval grave carried the genome of a plague bacterium that once terrified half the planet.

A bit of mammoth muscle from the Arctic still preserved the ghostly echo of gene activity from the Ice Age.

These are not just data points; they are time-stamped messages from a world that no longer exists.

If there’s one big “life lesson” from ancient DNA, it might be this: the past is never as simple as we thought, and we’re never as separate from it as we’d like to believe.

Our genomes are living archives, continuously edited by migration, love affairs, catastrophes, and lucky survivals.

Whether you’re fascinated by mammoths, pandemics, or the possibility that you’re 2% Neanderthal, ancient DNA invites you to see yourself as part of a story that stretches tens of thousands of years into the past and just as far into the future.

Conclusion: The Dead Are Talking, and We’re Finally Listening

From Neanderthal romances to mammoth genomes and mystery migrations across oceans, ancient DNA has turned prehistory into a data-rich detective story.

It has shown that our species is a patchwork of lineages, shaped by chance encounters, brutal pandemics, climate swings, and the occasional domestication of a wolf.

It has also reminded us that the past is not finished; it lives on in our bodies, our diseases, and our shared genetic inheritance.

As sequencing technologies get cheaper and better, we can expect even stranger and more spectacular discoveries.

Somewhere out there, in a museum drawer or a block of permafrost, more genomes are waiting to weigh in on the story of who we are and how we got here.

And if history has taught us anything so far, it’s this: whatever we think we know, ancient DNA is probably about to surprise us again.