Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First: “Not Nice” Usually Means “Not Comfortable”

- Before You Start: The “Don’t Accidentally Make It Worse” Checklist

- The 13-Step Plan to a Stranger-Friendly Dog

- Step 1: Rule out pain and surprises

- Step 2: Learn your dog’s “I’m not okay” signals

- Step 3: Find your dog’s threshold distance

- Step 4: Teach a U-turn cue (“Let’s Go!”)

- Step 5: Build an automatic “check-in”

- Step 6: Teach a calm station (mat or “place”)

- Step 7: Play the “Look at That” game (without the drama)

- Step 8: Use controlled “helper stranger” setups

- Step 9: Gradually reduce distancelike you’re dimming a light, not flipping a switch

- Step 10: Teach a polite greeting routine (with consent)

- Step 11: Create a visitor plan for your home

- Step 12: Generalize (because dogs don’t generalize)

- Step 13: Maintain the skill for life

- Common Mistakes That Slow Progress (and How to Fix Them)

- When to Get Professional Help

- Conclusion: Your Dog Doesn’t Need to Love EveryoneJust Feel Safe

- Real-World Experiences: What This Looks Like Outside the “Perfect Training Bubble”

Your dog is wonderful. Strangers are… also technically people. Yet the moment a neighbor says “Hi!” your pup transforms

into a barking TED Talk about why no one should make eye contact in this neighborhood.

The good news: most “not nice to strangers” behavior isn’t your dog being “bad.” It’s usually your dog being

uncomfortableand trying very hard to control the situation the only way they know how. With the right plan,

you can replace suspicion with confidence and teach polite greetings that won’t require you to apologize while being

dragged like a human water-ski.

First: “Not Nice” Usually Means “Not Comfortable”

Dogs don’t come with a built-in social script for strangers. When a new person appearsespecially one who’s tall,

loud, wearing a hat, carrying a box, or moving like a caffeinated squirrelyour dog may feel uncertain. Barking,

lunging, hiding, growling, or “freeze-staring” can be a dog’s way of saying, “I need space,” or “I don’t understand

what’s happening, so I’m going to manage it.”

Why dogs react to strangers

- Fear or lack of socialization: They didn’t get enough positive exposure to different humans early on, or they had scary experiences.

- Territorial instincts: “This is my house. I did not approve your calendar invite.”

- Leash frustration: On-leash greetings can feel trapped and tense, which makes big feelings bigger.

- Over-arousal: Some dogs aren’t afraidthey’re just too excited and don’t know how to be chill.

- Pain or health issues: Discomfort can reduce tolerance fast. If behavior changed suddenly, treat that as a clue.

Safety note (seriously, but not scary)

If your dog has snapped, bitten, or frequently escalates (hard lunges, teeth, repeated attempts to get to people),

focus first on management and safety while you work on behavior change. That can include distance,

barriers, and (for many dogs) comfortable basket muzzle training. It’s not a “bad dog” signit’s a seatbelt.

Before You Start: The “Don’t Accidentally Make It Worse” Checklist

1) Pick your dog’s currency

Behavior change runs on payment. Choose something your dog loves enough to rethink their life choices:

soft, smelly treats; tug; squeaky toys; or a game of “find it.” For stranger work, food is usually easiest because

it’s fast and clear. (Yes, you can absolutely buy your dog’s affection. It’s called training.)

2) Choose a calm training environment

Start where your dog can succeed: quiet street, big open park, or even your driveway. The goal is not to “test” your

dog with chaos. The goal is to teach your dog that strangers predict good thingsat a distance that feels safe.

3) Decide what “nice” means for your dog

“Nice” does not have to mean “lets every stranger hug them like a long-lost cousin.” A perfectly healthy goal is:

your dog can calmly look at strangers, stay relaxed, and move on. Friendly neutrality is a win.

The 13-Step Plan to a Stranger-Friendly Dog

Step 1: Rule out pain and surprises

If the behavior is new or suddenly worse, schedule a vet check. Pain (ears, hips, dental issues), thyroid changes,

and other health problems can shrink your dog’s patience. Even if your dog is “fine,” a quick medical rule-out

makes training clearer.

Step 2: Learn your dog’s “I’m not okay” signals

Dogs rarely jump straight to biting. Most whisper before they shout. Watch for lip licking, turning the head away,

stiff body, tucked tail, pinned ears, whale eye, pacing, sudden sniffing, freezing, or low growls.

Your job is to notice the whispers and increase distance before your dog feels the need to yell.

Step 3: Find your dog’s threshold distance

Threshold is the distance where your dog can notice a stranger and still think, eat, and respond to you.

If your dog can’t take treats, won’t look away, or is barking/lunging, you’re too close. Back up until your dog

can breathe againthen train there. Progress happens fastest when your dog feels safe.

Pro tip: the first “win” often looks boring. If you’re thinking, “This is too easy,” congratulationsyour dog can

learn in this moment. Keep it easy.

Step 4: Teach a U-turn cue (“Let’s Go!”)

A reliable exit strategy prevents ugly moments and keeps your dog’s brain online. In a quiet area, say “Let’s go!”

in a cheerful voice, turn 180 degrees, and feed treats as your dog follows. Practice until it’s automatic.

Later, when a stranger appears too close, you’ll have a polite getaway instead of a dramatic scene.

Step 5: Build an automatic “check-in”

Reward your dog for choosing to look at you. Start indoors: your dog glances at your face → mark (“yes!”) → treat.

Then practice in the yard, then on walks. A dog who checks in is a dog who can ask, “What’s the plan?” instead of

improvising chaos.

Step 6: Teach a calm station (mat or “place”)

A mat becomes your dog’s “safe job.” Toss a treat onto the mat; when your dog steps on it, reward. Add duration

slowly (seconds first), then add a cue (“place”). This skill becomes gold when guests arrive or when you need your

dog to relax instead of hosting their own security briefing.

Step 7: Play the “Look at That” game (without the drama)

Here’s the magic: your dog looks at a stranger → you mark (“yes!”) → treat. Your dog is allowed to look; looking is

not a failure. We’re teaching, “Strangers make snacks happen.” Over time, the emotional response shifts from

“uh-oh” to “oh hey, it’s the treat dispenser festival.”

Keep sessions shortthink 3 to 10 minutes, not an endurance sport.

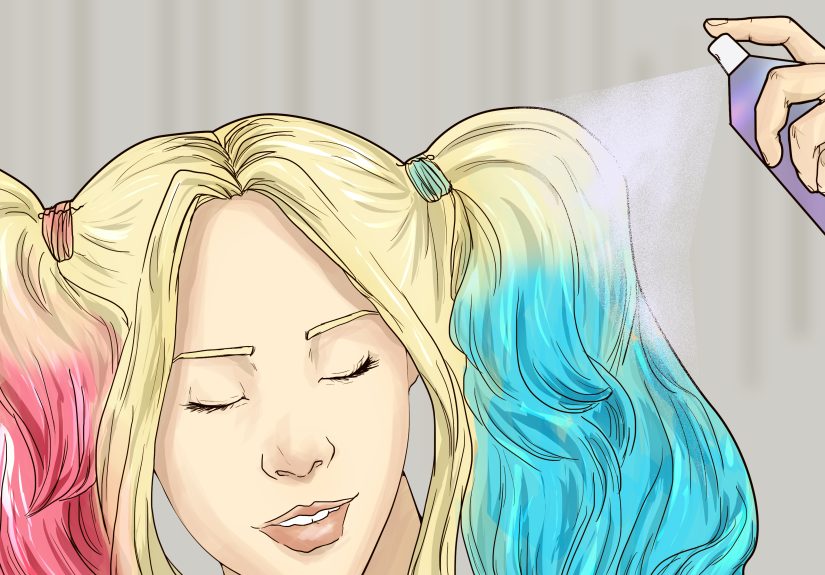

Step 8: Use controlled “helper stranger” setups

Pick a calm friend (the kind who can follow instructions, not the kind who says, “Dogs love me!” right before

looming over your dog). Ask them to:

- Stand sideways, avoid direct eye contact, and stay quiet.

- Toss treats on the ground away from themselves, so your dog can eat while keeping distance.

- Let your dog decide if they want to approach (no reaching hands).

Your role: keep your dog under threshold, reward calm behavior, and end the session while it’s going well.

Step 9: Gradually reduce distancelike you’re dimming a light, not flipping a switch

Move closer only when your dog is consistently relaxed: loose body, able to take treats, able to look away and

check in. Reduce distance in tiny increments (a few feet, not a full send). If your dog reacts, that’s feedback:

increase distance, lower difficulty, and try again later.

Think of progress as a staircase. Some days you step up; some days you rest on the same step. And sometimes you

realize you left your snacks on the first floor and go back down. Normal.

Step 10: Teach a polite greeting routine (with consent)

When your dog is ready for closer interaction, teach a predictable script:

- Approach calmly (no dragging, no tight leash).

- Pause a few feet away; reward your dog for calm.

- “Go say hi” and allow a 1–2 second sniff (then call your dog back and reward).

- Consent check: if your dog returns happily, you can repeat; if they lean away, freeze, or avoid, you’re done.

If petting happens, ask strangers to pet under the chin or on the chestnot a big hand swooping over the head

like a surprise helicopter.

Step 11: Create a visitor plan for your home

Many dogs who can handle strangers outside lose it when people enter their space. For home greetings, structure is

your best friend:

- Management first: use a baby gate, leash, or separate room during arrivals.

- Mat station: send your dog to “place” and reward calm.

- Treat rain: ask guests to toss treats past the dog (not hand-feed) so your dog can approach/retreat comfortably.

- Ignore is kind: tell guests: no eye contact, no leaning, no high-pitched hype until your dog is relaxed.

Once your dog is calm, you can allow brief, structured interactions. If your dog escalates, go back to management.

That’s not “failure”that’s a smart plan.

Step 12: Generalize (because dogs don’t generalize)

Your dog might be cool with your neighbor Sue but suspicious of “Sue wearing sunglasses and carrying a yoga mat.”

Practice with a variety of people: different heights, ages, voices, hats, uniforms, canes, strollers. Start each

new “category” at an easier distance again. This is how you build a truly socialized, confident dog.

Step 13: Maintain the skill for life

Once things improve, don’t quit cold turkey. Keep paying your dog occasionally for calm behavior around strangers.

Think of it as a lifelong subscription to Good Choices™. Also, protect your dog from being rushed, cornered, or

forced into greetings. Confidence grows when your dog trusts you to advocate for them.

Common Mistakes That Slow Progress (and How to Fix Them)

Mistake: Forcing interaction

Dragging your dog toward people or insisting “he has to get used to it” often backfires. Replace force with

controlled distance and positive associations.

Mistake: Punishing warning signs

Growling is information. If you punish it, you may remove the warning and keep the feelingcreating a dog who skips

straight to snapping. Instead, thank your dog for communicating, increase distance, and train the underlying emotion.

Mistake: Going too close too soon

If your dog is reacting, learning can’t happen. Training is easiest when your dog can still take treats and respond

to cues. Distance is not “letting your dog win.” Distance is how you keep the brain online.

When to Get Professional Help

If your dog has bitten, if the behavior is escalating, or if you feel unsafe, bring in a qualified professional.

Look for a credentialed trainer who uses reward-based methods and has experience with reactivity and aggression.

For complex cases, a board-certified veterinary behaviorist can assess medical factors and, when appropriate,

discuss behavior medication as part of a broader plan.

Conclusion: Your Dog Doesn’t Need to Love EveryoneJust Feel Safe

Teaching your dog to be nice to strangers is really about teaching your dog that strangers are predictable, safe,

and not a personal threat. Use distance, rewards, and a step-by-step plan that respects your dog’s emotions.

Celebrate small wins: a calm glance, a relaxed body, a quiet walk-by. Those moments add up fast.

And remember: a dog who chooses calm is not “being controlled.” They’re learning confidenceone snack, one safe

repetition, and one successful greeting at a time.

Real-World Experiences: What This Looks Like Outside the “Perfect Training Bubble”

Training around strangers rarely happens in a tidy laboratory where everyone reads your dog’s body language and

nobody suddenly jogs out of a bush. Real life is messy, which is exactly why a simple, repeatable plan matters.

Here are a few common scenarios dog owners run intoand what tends to help most.

1) The “Mail Carrier = Apocalypse” phase

Many dogs react to delivery people because the pattern feels suspicious: stranger appears, approaches the house,

drops something, leaves. To your dog, that’s a heist movie. Owners often get traction by pairing the sight of the

delivery person with a rapid “treat party” at a window or behind a gate. The goal isn’t to stop the dog from

noticingit’s to change what noticing means. Over time, the routine becomes: “Person at the door? Great.

Snacks rain from the sky and we practice going to our mat.” Some dogs even start jogging to their station the moment

they hear the truck, like tiny furry employees clocking in for a shift.

2) The friend who tries too hard

Dogs who are uncertain about strangers usually struggle most with people who move quickly, talk loudly, or reach

directly toward the dog’s face. A helpful adjustment is teaching guests to be “boring on purpose.” When visitors

come in, they ignore the dog, avoid eye contact, and casually toss treats away from themselves. This lets the dog

approach and retreat without pressure. Owners are often surprised: the moment the guest stops trying to befriend

the dog, the dog gets curious and chooses to investigate. It’s like middle school all over againconfidence is

magnetic, desperation is loud.

3) The “He’s friendly!” dog… who is friendly at 50 feet

Some dogs look social from a distance and then fall apart up close. That usually means the dog is okay with

strangers as background scenery, but not okay with strangers entering their personal space. In these cases, “nice”

can be redefined as calm walk-bys and relaxed observation. Owners often progress by practicing short “sniff and

retreat” greetingsone second of sniffing, then cheerfully calling the dog back for a reward. The dog learns they

can leave whenever they want, which paradoxically makes them more willing to approach.

4) The setback after “one bad moment”

It’s common to have a setback after someone surprises your dog, a child runs up, or a stranger reaches over your

dog’s head. The fix usually isn’t “train harder” so much as “make it easier again.” Owners get results by dropping

back to a comfortable distance for a week or two, rebuilding calm repetitions, and preventing surprise greetings

with better management (cross the street, use parked cars as visual blocks, practice U-turns). Setbacks don’t erase

progressthey just tell you what your dog still finds difficult.

5) The long-term win: a dog who chooses neutrality

One of the most satisfying outcomes isn’t a dog who begs strangers for attentionit’s a dog who notices strangers,

checks in, and continues the walk like it’s no big deal. Owners often describe this as “getting my life back”:

fewer tense walks, fewer apologies, and a dog who looks genuinely relieved to have a clear plan. That’s the heart

of this process: you’re not forcing friendliness. You’re building safety, predictability, and trustso your dog

doesn’t feel like they have to handle strangers all by themselves.