Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why MDS Can Hit Mental Health So Hard

- Common Mental Health Effects of MDS

- How Physical Symptoms Shape Mood (And What to Do About It)

- Treatment and Mental Health: What Changes Along the Way

- How to Know When It’s More Than “Normal Stress”

- Screening Tools That Can Make Mental Health “Visible”

- What Actually Helps: Practical Coping Strategies for MDS

- Caregivers: The Quiet Mental Health Crisis Nobody Schedules

- Conclusion: Treat Mental Health as Part of MDS Care

- Experiences Related to the Mental Health Effects of MDS (Composite Stories)

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) can be a master class in uncertainty: lab results that change week to week, treatments that help in one area but complicate another, and fatigue that can turn “simple errands” into an extreme sport.

While MDS is diagnosed and treated through blood counts and bone marrow tests, it also lives in the mindshaping mood, sleep, relationships, identity, and the way you plan (or don’t plan) for tomorrow.

This article breaks down the most common mental health effects linked to MDS, why they happen, and what actually helpswithout pep-talk fluff or toxic positivity. Expect practical strategies, specific examples, and a few gentle jokes,

because sometimes humor is the only thing with a stable platelet count.

Why MDS Can Hit Mental Health So Hard

MDS is often described medically as a group of disorders where the bone marrow doesn’t produce enough healthy blood cells. In real life, that can mean persistent fatigue, frequent infections, easy bruising or bleeding, and

a calendar that suddenly revolves around appointments and lab work.

What makes MDS emotionally intense isn’t just the diagnosisit’s the way the condition can behave like a long, unpredictable storyline. Some people live with lower-risk MDS for years with “watchful waiting” and supportive care.

Others face higher-risk disease that requires more urgent treatment decisions. Either way, your brain keeps trying to answer questions it can’t fully solve:

- “Is this tiredness normal… or is something changing?”

- “Are my numbers improving, or is that just a good week?”

- “How do I plan my life around a disease that refuses to RSVP?”

That constant uncertainty is a known driver of distress. And when distress is chronic, it can slide into anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and burnoutfor patients and caregivers alike.

Common Mental Health Effects of MDS

1) Anxiety: “Scanxiety,” Lab-Day Dread, and the Fear Loop

Anxiety with MDS often shows up around monitoring: blood draws, bone marrow biopsies, treatment cycles, or simply waiting for a call from the clinic. Even if you feel okay on a Tuesday, Thursday’s lab results can feel like a pop quiz

you didn’t study for.

Anxiety can be emotional (worry, irritability), physical (racing heart, tense muscles), or cognitive (difficulty focusing, constant “what if” thinking). It may also show up as avoidanceputting off appointments,

not opening patient portals, or trying to “not think about it” (which, of course, makes you think about it more).

2) Depression: When Fatigue and Loss Stack Up

Depression isn’t just sadness. With MDS, it can look like low motivation, loss of pleasure, social withdrawal, hopelessness, or feeling “emotionally flat.” It can also overlap with physical symptoms of MDSespecially fatigue.

That overlap is tricky: if you’re exhausted because of anemia, you might stop doing the activities that usually keep your mood steady, which can deepen depression.

A common emotional pattern is griefgrief for the life you had before, the energy you used to rely on, and the ease of making plans without checking your latest blood counts first.

3) Distress: The “Everything Is Too Much” Feeling

In cancer care, “distress” is a broad umbrella that includes emotional strain, practical stress (insurance, transportation, work), family concerns, spiritual questions, and symptom burden.

MDS can load every one of those categories at once.

Distress matters because it can affect treatment decisions, adherence, and quality of life. It’s also common for people to minimize itespecially if they’ve been told their disease is “lower risk,” as if feelings must obey risk categories.

Spoiler: they do not.

4) Sleep Problems: Insomnia, Fragmented Sleep, and “3 A.M. Research Mode”

MDS-related symptoms (fatigue, shortness of breath, discomfort), medication side effects, and anxiety can all disrupt sleep. Sometimes the mind starts “solving” at night:

replaying conversations, googling terms you definitely didn’t need at 3:07 a.m., and mentally time-traveling into worst-case scenarios.

Poor sleep then worsens mood and anxiety the next day, creating a loop that’s hard to break without a plan.

5) “Brain Fog” and Cognitive Strain

Many people with MDS describe brain fogslower thinking, trouble concentrating, forgetfulness, or feeling mentally “fuzzy.”

This can be linked to fatigue, low oxygen-carrying capacity from anemia, sleep disruption, stress hormones, and medication effects.

Brain fog can also be emotionally heavy because it changes how you function at work, at home, and in conversations. It’s frustrating, and frustration is rarely mood-neutral.

How Physical Symptoms Shape Mood (And What to Do About It)

A helpful rule of thumb: when your body feels unstable, your brain tends to go into threat-detection mode.

With MDS, physical symptoms can be persistentand persistent symptoms can steadily drain resilience.

Fatigue: Not Just “Tired,” More Like “Battery Missing”

Fatigue in MDS can be profound, and it doesn’t always match what you think it “should” based on a number on a lab report.

It can limit exercise, social life, and independencethree major mood protectors.

What helps:

- Energy budgeting: plan your day like you have a limited number of tokens. Spend them on what matters most.

- Micro-movement: short walks or gentle stretching can support mood without demanding a full workout.

- Symptom tracking with context: note sleep, transfusions, medication changes, and stressors so fatigue doesn’t feel random.

Infection Risk and “Hypervigilance”

Low white blood cell counts can raise infection risk, which can lead to constant vigilancemonitoring every cough, avoiding crowds, or feeling on-edge in public spaces.

That vigilance can be protective, but it can also become exhausting and isolating.

What helps: set boundaries that protect your health without shrinking your life to zero. For example, choose safer social options (outdoors, small groups, masks in crowded spaces when needed)

rather than “all or nothing” isolation.

Bruising, Bleeding, and the Fear of “One More Complication”

When platelets are low, it’s normal to feel more cautiousand sometimes more anxious.

People may avoid activities they enjoy or worry about normal bumps and bruises, which can create a constant background hum of stress.

What helps: ask your care team for clear safety thresholds (what’s safe, what’s not, when to call) so your decisions don’t have to be fueled by fear.

Treatment and Mental Health: What Changes Along the Way

MDS treatment varies widely, and mental health effects can shift across the journey. Supportive care, injections, transfusions, medications to boost blood counts,

disease-modifying therapies, and (for some) stem cell transplant each come with different emotional stressors.

Supportive Care and the Psychology of “Watchful Waiting”

Being told you’re being monitorednot “actively treated”can be emotionally complicated. On one hand, it may mean the disease is stable enough to watch.

On the other, it can feel like living with a ticking metronome: frequent labs, constant monitoring, and the sense that you’re waiting for the next shoe to drop.

People often describe feeling guilty for being upset (“I’m not even on chemo”) or feeling dismissed by others (“So you’re fine, right?”). Those reactions can increase isolation.

Transfusions and Clinic-Centered Life

If you need regular transfusions, life can start to revolve around infusion chairs, appointment scheduling, and the emotional whiplash of feeling better after a transfusionthen declining again.

This pattern can contribute to mood swings, frustration, and a sense of dependence that’s hard for fiercely independent people (translation: most humans).

Higher-Intensity Treatments and Emotional Side Effects

More intensive therapies can bring additional stress: side effects, time demands, infection precautions, and uncertainty about response.

Even when treatment is going well, many people feel emotionally “keyed up,” waiting for results or worrying about setbacks.

Stem Cell Transplant: High Stakes, High Stress

For people who pursue transplant, mental health support becomes even more important. Transplant can involve long hospital stays, isolation precautions, caregiver strain, fear of complications,

and a long recovery that tests patience in ways you didn’t know your personality could be tested.

It’s common to need structured support before and after transplanttherapy, medication management when appropriate, and practical help for daily life.

How to Know When It’s More Than “Normal Stress”

Feeling worried or sad after an MDS diagnosis is common. But certain signs suggest you’d benefit from professional support (and you don’t need to “earn” that support by suffering longer).

Consider extra help if you notice:

- Persistent low mood, numbness, or hopelessness most days for 2+ weeks

- Constant worry that interferes with sleep, focus, or relationships

- Panic symptoms (racing heart, shortness of breath, sudden intense fear)

- Loss of interest in things you usually enjoy

- Major sleep disruption or appetite changes

- Increased use of alcohol or substances to cope

- Feeling unable to cope with daily tasks

If you ever feel like you might hurt yourself or you’re not safe, get help immediately. In the U.S., you can call or text 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or go to the nearest emergency room.

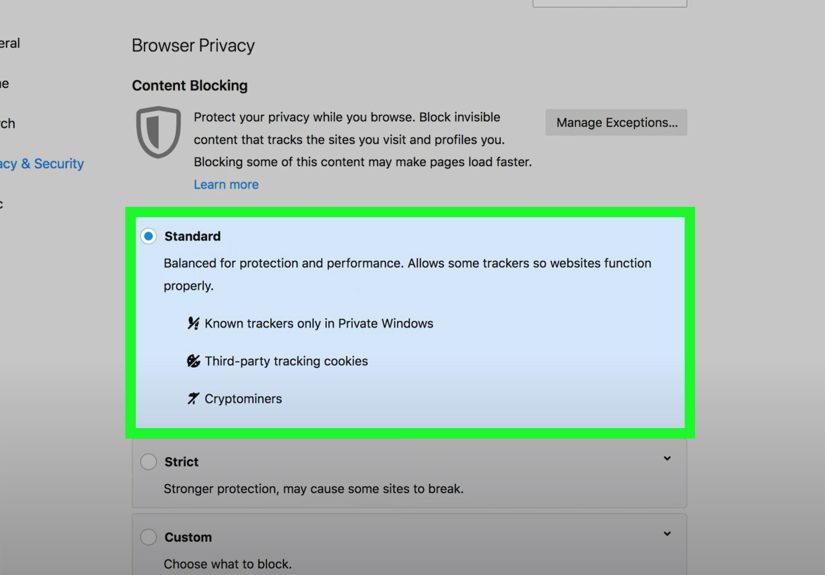

Screening Tools That Can Make Mental Health “Visible”

In many cancer settings, distress is treated like a vital signsomething you screen for regularly, not something you only address when it becomes a crisis.

Screening tools don’t replace conversation, but they can make it easier to say, “Hey, this is not fine.”

Common tools used in oncology settings include:

- Distress Thermometer (0–10): a quick rating of distress, often paired with a problem checklist (practical, emotional, physical, family).

- PHQ-9: a depression screening tool that helps track severity and changes over time.

- GAD-7: an anxiety screening tool that can help identify clinically significant anxiety.

If your clinic doesn’t ask about distress, you can bring it up yourself. A simple script:

“Physically I’m managing, but emotionally I’m struggling. Can we screen for distress or connect me with psychosocial support?”

What Actually Helps: Practical Coping Strategies for MDS

Build a “Two-Lane” Support Plan: Medical + Emotional

Many people focus on the medical lane (labs, transfusions, medications) and hope emotional stability appears as a side effect. Usually it doesn’t.

Consider mental health support part of treatmentnot an optional add-on.

- Medical lane: clear thresholds, symptom plan, question list for appointments.

- Emotional lane: therapy, support groups, coping skills, and (when appropriate) medication support.

Use “Appointment Anchors” to Reduce Anxiety

Anxiety spikes when everything feels uncertain. Anchors create predictability:

- Keep one running document for questions, symptoms, and medication changes.

- Ask your clinic when results will be available and who will call.

- Schedule something gentle after labs (coffee with a friend, a short walk, a favorite show).

Therapy Approaches That Fit Chronic Illness

Different therapy styles work for different needs, but these are commonly useful in serious illness:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): helps identify thought patterns that worsen anxiety/depression and replace them with more workable ones.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): helps you live by values even when symptoms and uncertainty persist.

- Supportive counseling / psycho-oncology: focuses on coping, adjustment, communication, and decision stress.

Therapy isn’t about pretending you’re okay. It’s about giving your brain better tools than catastrophic forecasting and stress-snacking.

Protect Your Identity (You Are Not a Lab Result)

MDS can shrink your identity to “patient,” especially if appointments are frequent. Protecting identity supports mental health.

Try a weekly “non-medical commitment”something small but meaningful that reminds you you’re still you:

- a hobby hour (even if it’s 20 minutes)

- a phone call with a friend

- a low-energy creative project

- a simple role you choose (mentor, grandparent, neighbor, volunteeradapted to your energy)

Talk About It Without Making People Panic

Some people avoid talking because they don’t want to worry others; others talk and feel like they’re “too much.”

A middle path is to be specific about what you need:

- Need listening: “I don’t need solutions right nowjust someone to hear me.”

- Need help: “Can you drive me to labs next Tuesday?”

- Need normal: “Let’s talk about anything except blood counts for 30 minutes.”

Caregivers: The Quiet Mental Health Crisis Nobody Schedules

Caregivers often carry invisible stress: juggling logistics, watching someone they love struggle, managing fear privately, and trying to “stay strong.”

Caregiver burnout is realand it’s not a moral failure; it’s a load problem.

Caregivers can protect their mental health by:

- Accepting help with specific tasks (rides, meals, errands)

- Getting their own counseling or support group

- Taking regular breaks (even short ones) without guilt

- Keeping up basic health maintenance (sleep, nutrition, medical appointments)

A good caregiving goal isn’t “never struggle.” It’s “struggle with support.”

Conclusion: Treat Mental Health as Part of MDS Care

MDS affects more than blood cellsit affects time, energy, confidence, and the emotional sense of safety we usually take for granted. Anxiety, depression, distress, sleep problems, and brain fog are not uncommon in MDS,

and they’re not signs of weakness. They’re signals that your system is carrying a heavy load.

The good news is that mental health support in cancer care is real, practical, and effective. Screening tools can make distress visible. Therapy and support groups can reduce isolation.

Medication support can be appropriate for some people, especially when anxiety or depression becomes persistent or severe.

The most important move is the simplest one: bring it up early, and treat it like part of carenot an afterthought.

Experiences Related to the Mental Health Effects of MDS (Composite Stories)

The experiences below are compositesbuilt from common themes patients and caregivers frequently describeso you can recognize patterns without anyone’s private details being exposed.

If you see yourself here, you’re not “overreacting.” You’re responding like a human in a hard situation.

“The Diagnosis Didn’t HurtThe Waiting Did.”

One person described the moment of diagnosis as strangely calm. The doctor explained the condition, the plan, the next steps. There were handouts.

There was a schedule. There was even reassurance: “We’ll monitor closely.” And that’s where the emotional weight began.

Each lab visit felt like a verdict. Not dramaticjust… definitive. If the numbers looked stable, there was relief that lasted about a day. Then the brain returned to its favorite hobby:

imagining future scenarios with no invitation and very loud music.

Over time, they noticed “lab-day dread” creeping into ordinary life. Sunday evenings became tense because Monday was testing day. They snapped more easily at family.

They avoided planning vacations because it felt like tempting fate. The turning point wasn’t a perfect set of resultsit was naming what was happening:

“This is anxiety, and it’s taking up too much space.” Once they said that out loud, it became easier to ask for help instead of trying to white-knuckle it.

“Transfusion Day Was My Reset Button… Until It Wasn’t.”

Another person described transfusions like charging a phone that never holds a full battery. The day after, they felt almost normalenough energy to grocery shop, cook, and answer messages.

But the week progressed, and fatigue returned. The emotional swing was real: hope, function, decline, frustration. It became tempting to measure their worth by productivity

and when productivity dropped, self-criticism filled the gap.

What helped was switching from a “productivity identity” to a “values identity.” Instead of asking, “What did I accomplish today?” they began asking,

“What did I protect todaymy relationships, my comfort, my peace?” They built small rituals around transfusion days:

a podcast for the drive, a cozy meal after, a low-pressure plan for the next morning. The ritual didn’t fix the disease, but it reduced the emotional whiplash.

“I Felt Guilty for Being Depressed Because My Doctor Said ‘Lower Risk.’”

A common experience in MDSespecially for those labeled “lower risk”is the mismatch between how others view the diagnosis and how it feels to live with it.

Friends might say, “At least it’s not the aggressive kind,” or “Sounds like you’re okay.” The person hearing that might be dealing with relentless fatigue, frequent appointments,

and constant uncertainty. The result is a lonely form of shame: “Maybe I’m not allowed to feel this bad.”

When they finally spoke to a counselor, the counselor normalized the grief response: chronic illness changes your life even if you’re not in the hospital.

They also worked on language to help others understand: “My doctors are encouraged, but day-to-day it still affects me a lot.”

That one sentence helped them get support without feeling like they were dramatizing.

“Caregiving Made Me Strong… and Then It Made Me Empty.”

Caregivers often describe running on adrenaline at firstorganizing appointments, learning new terms, tracking medications, keeping the household steady.

They may be praised for being “so strong,” which can accidentally trap them in a role where they feel they’re not allowed to fall apart.

Months later, the adrenaline fades. That’s when burnout can appear: irritability, numbness, sleep problems, and guilt for feeling anything other than gratitude.

One caregiver described finally accepting help when they realized their “strength” was actually isolation. They began delegating tasksrides, meal trains, pharmacy pickups

and scheduled a weekly break that was non-negotiable. The break wasn’t luxurious; sometimes it was a quiet walk in a parking lot. But it restored enough oxygen to keep going.

Their key lesson: caring for someone else works better when you stop treating your own needs as optional.

“I Learned to Live in ‘Good Enough’ Instead of Perfect.”

Many people with MDS eventually develop a new emotional skill set: living in “good enough.” Not in a defeated waymore like practical wisdom.

“Good enough” means taking medications as planned most days, asking questions when confused, showing up to appointments, and letting yourself rest without arguing with your body.

It means building a life that adapts to symptoms rather than constantly fighting them.

One patient joked, “My new hobby is canceling plans in advance.” The humor landed because it was true. But they also began making plans that matched reality:

shorter visits, earlier meetups, flexible options, and honest check-ins. The emotional benefit was huge: less guilt, less pressure, and more genuine connection.

They weren’t pretending MDS was easy. They were making it livable.