Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “XYXYY” Usually Points To (And What It Doesn’t)

- A Quick Primer: How Extra X or Y Chromosomes Happen

- The Most Common “Extra Y” Variation: 47,XYY

- A Rarer (But Important) Relative: 48,XXYY

- Mosaic Patterns: When Chromosomes Vary by Cell

- Signs That Can Lead to Testing

- Diagnosis: From “Screening” to “Confirmed”

- Support and Treatment: What Actually Helps

- Practical Examples: What “Good Support” Can Look Like

- Myths to Retire (Politely, but Firmly)

- Conclusion: The Real Point of Understanding “XYXYY”

- Experiences Related to “XYXYY” (What Families and Adults Often Describe)

“XYXYY” looks like a secret handshake made of chromosomes. And honestly? That’s not far off.

It’s not a standard medical diagnosis label you’ll see on a lab report. In real-world genetics,

clinicians typically use a karyotype (a chromosome count + pattern) like 47,XYY

or 48,XXYY rather than a letter-string like “XYXYY.”

Still, people sometimes write “XYXYY” as shorthand when they’re talking about a family of conditions involving

extra X and/or Y chromosomesespecially variations that include an extra Y. This article uses “XYXYY”

as an umbrella term to explain what extra-Y chromosome variations are, what they can look like in everyday life,

and how families and adults can navigate diagnosis, support, and the occasional “Wait… what does this even mean?”

moment.

What “XYXYY” Usually Points To (And What It Doesn’t)

Most people learn in school that typical sex chromosomes are XX for females and XY for males.

In genetics clinics, “X and Y chromosome variations” (also called sex chromosome aneuploidies) are conditions where someone

has more or fewer X and/or Y chromosomes than expected.

The “extra Y” neighborhood commonly includes:

- 47,XYY (sometimes called XYY syndrome; older nicknames exist, but many clinicians avoid them)

- 48,XXYY (a rarer condition that can share some overlap with Klinefelter-related features)

- Mosaic patterns (where not every cell has the same chromosome set, such as 46,XY/47,XYY)

- Very rare higher-count variations (e.g., multiple extra sex chromosomes), typically discussed case-by-case

Important note: having an X/Y variation does not define a person’s personality, intelligence, or future.

These conditions are often highly variablemeaning two people with the same karyotype can have very different

strengths and challenges.

A Quick Primer: How Extra X or Y Chromosomes Happen

Most X and Y chromosome variations occur because of a random “copying/splitting” error during the formation of sperm or egg cells,

called nondisjunction. That’s science-speak for: chromosomes didn’t separate the way they usually do.

It’s typically not inherited and is not caused by anything a parent did or didn’t do.

Sometimes, the change happens after conception as cells divide, which can lead to mosaicisma mix of chromosome

patterns across different cells in the body. Mosaicism can influence how noticeable symptoms are, but it doesn’t guarantee “milder”

or “more severe.” Biology loves exceptions.

The Most Common “Extra Y” Variation: 47,XYY

What it is

In 47,XYY, a person assigned male at birth has one X chromosome and two Y chromosomes in many or all cells.

Many individuals have subtle or no obvious physical differences, and some are never diagnosed.

Commonly discussed traits (with lots of individual variation)

- Taller-than-average height (often the most consistent physical trait)

- Speech and language delays in childhood for some

- Learning differences, especially in language-based skills, for some

- Attention, behavioral, social, or emotional challenges may be more common than in peers

Research and clinical guidance often emphasize that the increased risk of ADHD, anxiety, depression, and autism-spectrum diagnoses

is a risknot a destiny. Many people with 47,XYY do well with early supports, appropriate school accommodations,

and mental health care when needed.

A Rarer (But Important) Relative: 48,XXYY

What it is

48,XXYY includes an extra X and an extra Y chromosome in a person assigned male at birth.

Like 47,XYY, it’s variablebut it’s often associated with a more consistent pattern of developmental and medical considerations.

Common features clinicians watch for

- Developmental delays in early childhood (especially speech/language)

- Learning challenges and executive function differences (planning, organization, impulse control)

- Hypogonadism / lower testosterone emerging around adolescence for many

- Fertility issues are common

- Higher risk of certain health concerns (which may include metabolic issues, tremor, and other organ-specific concerns)

The practical takeaway: 48,XXYY often benefits from a team approachpediatrics, speech/OT supports, school services,

and, later, endocrinology and fertility counseling as appropriate.

Mosaic Patterns: When Chromosomes Vary by Cell

You might see mosaic descriptions like 46,XY/47,XYY. This means some cells have a typical XY pattern,

while others have an extra Y. Mosaic patterns can show up for many reasons, and sometimes they’re discovered incidentally during

genetic testing for another concern.

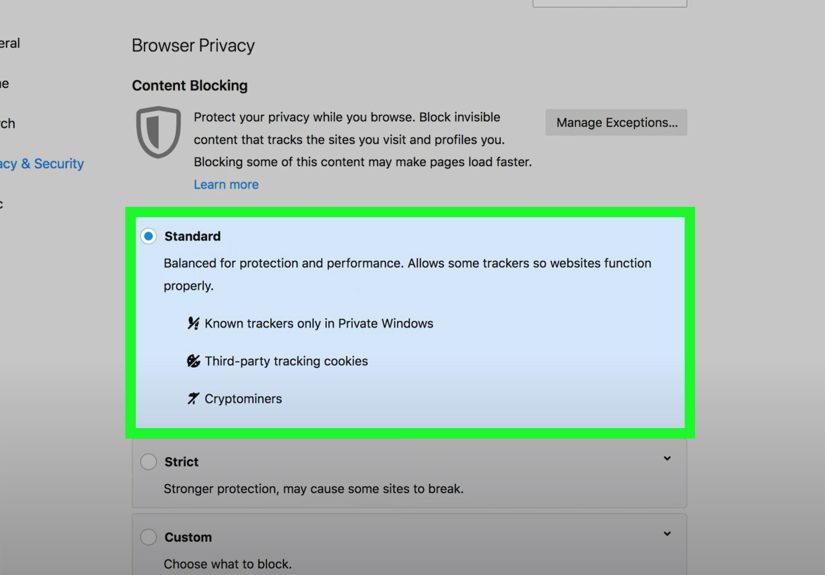

If “XYXYY” brought you here because you saw confusing letters on a test result, your best move is to request:

(1) the full karyotype report and (2) a genetics consult to translate it into plain English.

Genetics reports can feel like they were written for a committee of robotskind robots, but robots nonetheless.

Signs That Can Lead to Testing

Many people with extra X/Y variations are diagnosed in one of three ways: prenatal screening follow-up, evaluation for developmental delays,

or later-life workups for puberty/fertility issues. Common reasons families seek answers include:

In early childhood

- Speech/language delay (late talking, articulation issues, difficulty with expressive language)

- Motor delays or low muscle tone

- Learning concerns once school starts (reading, writing, attention, working memory)

- Behavioral regulation struggles (big feelings, impulsivity, sensory sensitivities)

In adolescence and adulthood

- Concerns about puberty timing, energy levels, or muscle development

- Low testosterone symptoms (which can include fatigue, low libido, mood changesdepending on age)

- Fertility challenges

- Ongoing executive function struggles (organization, time management)

None of these signs are exclusive to X/Y variations. That’s why diagnosis often requires a combination of clinical context and testing.

Diagnosis: From “Screening” to “Confirmed”

Prenatal screening methods (like noninvasive prenatal screening/testing, often called NIPT) can flag sex chromosome differences,

but screening is not the final word. Confirmation typically involves diagnostic testing such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS),

amniocentesis, or postnatal chromosome testing (like a karyotype).

After birth, testing may be recommended when developmental patterns or medical concerns suggest a chromosomal condition.

A genetics professional can explain what tests were done (karyotype, microarray, or other methods), what the result means,

and what follow-up makes sense.

Support and Treatment: What Actually Helps

There’s no single “cure” for chromosome variations, because the chromosome pattern is part of the body’s blueprint.

The goal is support: identify needs early, build skills, reduce stressors, and protect physical and mental health.

1) Early intervention and therapy (when needed)

- Speech-language therapy for articulation, expressive language, and pragmatic/social communication

- Occupational therapy for fine motor skills, sensory processing, and daily living routines

- Physical therapy for strength, coordination, and low muscle tone

2) School supports that match the child (not the label)

Many kids benefit from targeted accommodationspreferential seating, extra time, reading support, speech services, or executive function coaching.

The most effective plan is based on observed needs, not assumptions about a diagnosis.

3) Behavioral and mental health care

If attention challenges, anxiety, depression, or social difficulties show up, evidence-based approaches like behavioral therapy,

skills-based coaching, and (when appropriate) medication can help. A diagnosis can be a door to resourcesnot a verdict.

4) Endocrine and reproductive health support

For conditions like 48,XXYY where low testosterone is more common, clinicians may monitor puberty and hormone levels.

If hormone therapy is recommended, it should be individualized with careful follow-up.

Fertility counseling can also be helpful for teens and adults, especially when family planning is a priority.

5) Community and advocacy

Families often benefit from connecting with reputable organizations and clinics that specialize in X and Y chromosome variations.

Advocacy groups can provide practical guides, support groups, and “you’re not alone” energywhich is sometimes the most underrated intervention.

Practical Examples: What “Good Support” Can Look Like

Example A: A preschooler with speech delay

A 3-year-old is tall for age, has a strong interest in building toys, but struggles to form sentences and gets frustrated.

The pediatrician recommends speech therapy and a developmental evaluation. A chromosome test later reveals 47,XYY.

The child continues speech therapy, the family learns strategies for emotional regulation, and the preschool provides structured transitions.

Result: fewer meltdowns, better communication, and a diagnosis that informs support without limiting expectations.

Example B: A middle schooler who “knows the material” but can’t turn in homework

A student tests well but forgets assignments, loses materials, and feels overwhelmed. Testing identifies executive function needs.

With or without an X/Y diagnosis, the support plan is similar: a homework system, reduced organizational load, a weekly check-in teacher,

and coaching on planning. The label matters less than the blueprint for day-to-day success.

Example C: A teen with fatigue and delayed puberty signs

A teen assigned male at birth is struggling with low energy and delayed pubertal development. Endocrine testing suggests low testosterone,

and genetic testing identifies 48,XXYY. With a guided plan, the teen receives appropriate medical follow-up, mental health support,

and realistic conversations about fertility optionswithout shame or doom.

Myths to Retire (Politely, but Firmly)

- Myth: “Extra Y means aggression.”

Reality: Behavior is shaped by many factorsenvironment, support, mental health, and individual temperament.

Simplistic stereotypes aren’t supported by modern clinical understanding. - Myth: “A diagnosis tells you exactly how life will go.”

Reality: Variability is the rule. The diagnosis helps identify risks and supports, not a fixed storyline. - Myth: “If my child has this, it must be inherited.”

Reality: Many X/Y variations are random events during cell division.

Conclusion: The Real Point of Understanding “XYXYY”

If “XYXYY” brought you here, you’re probably trying to decode a result, a note, or a conversation that felt like it skipped the subtitles.

Here’s the plain-English ending: extra X/Y chromosome variationsespecially those involving an extra Ycan be associated with differences in

development, learning, behavior, and (in some conditions) hormones and fertility. But they’re also compatible with happy lives, strong relationships,

meaningful careers, and kids who grow into themselves in their own way.

The best next step is usually the same: confirm what the actual karyotype is, ask a genetics professional to explain it in human terms,

and then focus on supports that make day-to-day life easier. If you do that, “XYXYY” stops being a scary code and becomes what it should be:

a clue that helps you build better support.

Experiences Related to “XYXYY” (What Families and Adults Often Describe)

Because “XYXYY” is often used informally, people’s experiences vary depending on whether they’re actually dealing with 47,XYY, 48,XXYY,

a mosaic pattern, or another X/Y variation. But there are some common threads that show up again and again in support communities and clinics.

Think of these as “frequently lived moments,” not universal truths.

1) The diagnosis is often discovered sideways.

Many parents describe not setting out to “find a chromosome variation.” They’re looking for answers to something practical:

a speech delay, school struggles, attention concerns, anxiety, or puberty questions. The diagnosis arrives as a surprise

sometimes during prenatal testing, sometimes after a developmental evaluation, and sometimes in adulthood during fertility workups.

A lot of families say the first emotional beat is confusion: “We didn’t even know this existed.”

2) Relief and worry can show up in the same sentence.

It’s common to feel reliefbecause there’s an explanation and a path to serviceswhile also feeling worried about what the label might imply.

Parents often describe spiraling into old stereotypes they find online (which can be outdated or sensationalized).

What tends to help is speaking to clinicians who work with X/Y variations regularly and connecting with reputable organizations

that focus on practical support. In other words: fewer scary headlines, more real-life guidance.

3) The day-to-day challenges are usually about skills, not “character.”

Families frequently describe that the hardest parts are executive function and communication hurdles:

organizing schoolwork, transitioning between tasks, regulating big feelings, reading social cues, and handling sensory overload.

The good news is that these are skill areas where targeted support can make a visible difference.

Many caregivers describe a turning point when accommodations become routine rather than a “special request.”

A planner system, consistent structure, and teacher check-ins can feel smallbut they can change a kid’s entire week.

4) Adolescence can bring a new chapter: identity, emotions, and sometimes hormones.

Teens may wrestle with self-esteem, friendships, and “Why is this harder for me?” questionswhether or not they talk about it out loud.

For some conditions like 48,XXYY, families also describe navigating medical monitoring and conversations about testosterone and fertility.

The best experiences tend to involve honest, age-appropriate information: not catastrophizing, not hiding, and not making the teen feel like

their body is a problem to be fixed. Many adults say they wish they’d been told earlier in a supportive way, because it would have helped them

understand themselves and advocate for what they needed.

5) Community matters more than most people expect.

A recurring theme is the power of meeting others with similar chromosome variations. People often describe finally hearing:

“Oh wow, you too?”and feeling their shoulders drop. Parents trade school strategies. Adults trade workplace coping tools.

Teens realize they’re not the only ones who find organization exhausting or social situations confusing.

When support is framed as skills-building (not “fixing a broken person”), many individuals describe gaining confidence and momentum.

Ultimately, the most consistent “experience” is that the chromosome label is only one part of the picture.

People aren’t living out a karyotypethey’re living out a full human life. “XYXYY” becomes meaningful when it helps someone get earlier support,

better health monitoring, and kinder self-understanding. And if it does that? Then it’s doing its job.