Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Who Was Derek Jarman (and Why Does His Garden Matter)?

- Where Is Derek Jarman’s Garden? Welcome to Dungeness: Coastal, Surreal, and Slightly Post-Apocalyptic

- How Do You Garden on Shingle? Derek Jarman’s “Against-the-Odds” Method

- Stones, Driftwood, and Found Objects: The Garden as Sculpture

- The Garden as Diary, Sanctuary, and Protest

- What We Can Learn from Derek Jarman’s Garden (Without Moving to a Shingle Beach)

- Books and Viewing That Deepen the Story

- Experiences: What Derek Jarman’s Garden Feels Like (A 500-Word Immersion)

- Conclusion: A Garden That Refuses to Be Small

If you’ve ever looked at a patch of gravel and thought, “Well, this is basically a botanical dead end,” Derek Jarman’s garden is here to politely laugh at youthen hand you a trowel.

Built around his black, yellow-trimmed cottage on the shingle at Dungeness, this “garden” is part horticulture, part sculpture, part diary, and part stubborn love letter to living when life is being aggressively unhelpful.

This is not the kind of garden that whispers, “Please don’t step on the lawn.” It doesn’t even have a lawn. It’s the kind of garden that says, “Step where you likejust watch out for the wind, the salt, and the existential dread.”

Who Was Derek Jarman (and Why Does His Garden Matter)?

Derek Jarman (1942–1994) was a filmmaker, painter, writer, designer, and activistone of those infuriatingly talented people who makes you wonder if sleep is actually optional.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the AIDS crisis tore through communities and official responses lagged (to put it politely), Jarman turned a remote stretch of English coastline into a working studioand a living artwork.

His garden at Prospect Cottage isn’t famous because it’s “pretty” in the traditional sense. It’s famous because it’s intentional.

It’s a place where beauty is made from scarcity, where the landscape is included rather than excluded, and where making something alive becomes a form of resistance.

Where Is Derek Jarman’s Garden? Welcome to Dungeness: Coastal, Surreal, and Slightly Post-Apocalyptic

Prospect Cottage: a small house with a huge attitude

The garden wraps around Prospect Cottage, Jarman’s home at Dungeness on the southeast coast of England.

The cottage looks like a graphic designer’s dream: dark exterior boards with vivid yellow trimbold enough to hold its own against a wide, open horizon and the not-so-subtle presence of a nearby nuclear power station.

Dungeness: shingle “desert” energy, minus the cactus stereotypes

Dungeness is an unusual place to plant anything that isn’t heartbreak. It’s a sprawling shingle landscapesunny, dry, salty, and windswept.

Picture a beach made of stones and sea air, dotted with weathered huts, rusted textures, and the kind of light that makes photographers forget to eat.

This setting matters because Jarman didn’t try to “escape” it. He treated it as part of the composition.

In his world, the view wasn’t a distraction; it was a collaborator. The garden doesn’t end neatly at a fence lineit visually runs outward, letting the landscape keep talking.

How Do You Garden on Shingle? Derek Jarman’s “Against-the-Odds” Method

If you’re imagining rich black soil and a tidy border, Derek Jarman’s garden will gently (or not gently) correct you.

This is a garden built on gritliterally. It’s a masterclass in working with constraints instead of pretending they don’t exist.

1) Start with what the place will allow

Shingle gardening means you’re dealing with low nutrients, fast drainage, intense wind, and salt spray. Translation: the environment is not here to help your feelings.

Jarman leaned into hardy, coastal-friendly plants and let the site’s natural character set the rules.

2) Build microclimates like you’re designing tiny weather systems

One of the quiet genius moves at Prospect Cottage is how the garden uses shape and placement to create shelter.

Beds, mounds, and little protected corners help plants establish themselves.

Over time, fallen leaves and plant matter begin to create a thin layer of soilnature doing overtime, paid in sunlight.

3) Use plants that can handle drama

The planting style isn’t about fussy perfection. It’s about color, toughness, and surprise.

You’ll see coastal and drought-tolerant species alongside self-seeders that appear like unplanned miracles.

Think poppies blowing in the wind, silvery foliage that doesn’t mind being sandblasted, and structural plants that look like they were designed by someone with a flair for the theatrical.

Plant examples and the logic behind them

While exact plant inventories shift with seasons and stewardship, the garden is widely associated with a mix of:

- Poppies (including California poppies): fast color, self-seeding optimism.

- Sea kale: a true coastal tough-guy with sculptural presence.

- Cotton lavender: silvery texture that laughs at poor soil.

- Succulents: water-wise survivors for exposed spots.

- Salvias: pollinator-friendly color with stamina.

- Figs (in sheltered microclimates): because sometimes you dare the place to say no.

The point isn’t to copy-paste this exact list into your yard. The point is the strategy: choose plants that belongor could plausibly belongwhere you live, and you’ll spend less time “fighting” the site and more time enjoying it.

Stones, Driftwood, and Found Objects: The Garden as Sculpture

Jarman didn’t treat hardscape as background. He treated it as language.

Flint stones, shells, driftwood, and beach-found objects become markers, lines, circles, and symbols.

The garden reads like a hand-made mappart geometry, part spell, part “I was walking on the beach and the universe handed me a good idea.”

This is where the garden becomes unmistakably Jarman: it’s not just planting design, it’s visual composition.

Repetition (stone circles), contrast (black cottage vs. bright flowers), and rhythm (objects placed like punctuation) give the space its signature pulse.

Why the geometry matters

In a conventional garden, geometry can feel controlling. Here, it feels grounding.

The shingle is visually chaoticthousands of stones, shifting light, relentless openness.

A circle of flint or a line of arranged rocks becomes an anchor: a small human “yes” set against a vast “who knows.”

The Garden as Diary, Sanctuary, and Protest

Derek Jarman’s garden is frequently discussed as a “private utopia,” but that phrase can make it sound like a retreat from the world.

It wasn’t. It was a way of meeting the worldespecially a world that was failing people.

AIDS era resiliencebeauty as survival, not decoration

Jarman began shaping Prospect Cottage and its garden during a period when he was openly living with HIV, as friends and peers were dying around him.

In that context, gardening isn’t a quaint hobby. It’s a daily practice of attention, care, and future-thinkingeverything a crisis tries to steal.

Writers and critics often return to the garden as an example of “reparative” creativity: not escapism, but repairemotional, cultural, ecological.

The garden doesn’t pretend the pain isn’t there; it plants right next to it.

Film, writing, and the landscape as set

Prospect Cottage wasn’t only a home. It became an engine room for art.

The Dungeness landscape appears in Jarman’s creative work, including film projects that blend personal vision with political rage and tenderness.

In this sense, the garden is both subject and stagealive, changing, and in dialogue with everything he made.

What We Can Learn from Derek Jarman’s Garden (Without Moving to a Shingle Beach)

You don’t need a nuclear power station in your view to take lessons from Prospect Cottage (though if you have one, please consider charging admission).

The garden’s influence shows up today in gravel gardening, climate-adapted planting, and the broader idea that gardens can be expressivepolitically, emotionally, aesthetically.

Lesson 1: Constraints can be a design brief

Bad soil? Harsh wind? Too much sun? Instead of forcing a style that doesn’t fit, start with what your site is already telling you.

Jarman’s approach suggests a mindset shift: don’t wage war on your conditions; design with them.

Lesson 2: Mix “native-ish” toughness with a few bold experiments

A garden becomes memorable when it balances belonging and surprise.

Use regionally adapted plants as your foundation. Then add a few carefully placed “maybe this will work” experiments where microclimates allow.

That’s how you get drama without constant emergency watering.

Lesson 3: Let the garden be more than plants

Jarman’s garden is filled with objects and gesturesstones in patterns, driftwood forms, visual jokes, quiet memorials.

Even in a small yard or balcony, you can build meaning with repetition, found materials, and deliberate placement.

It’s a reminder that gardening isn’t only biology; it’s storytelling.

Lesson 4: Leave room for the wild

The Prospect Cottage ethos isn’t “control everything.” It’s “notice everything.”

Self-seeders, spontaneous arrivals, and “weeds” become part of the texture.

If you want a garden that feels alive, you have to allow it to act aliveoccasionally messy, occasionally brilliant, and frequently uninterested in your schedule.

Books and Viewing That Deepen the Story

If you want to go beyond the highlight-reel version of Derek Jarman’s Garden, these are the core works that keep coming up in serious discussions of Prospect Cottage:

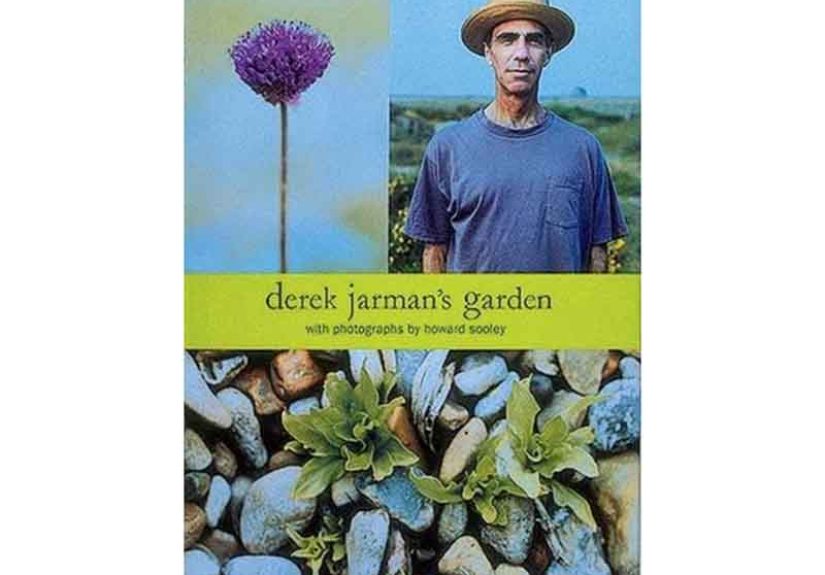

- Derek Jarman’s Garden (book): a visual and narrative record of how the garden evolved, with photography documenting the space through seasons and years.

- Modern Nature (journal/diary): a deeply affecting hybrid of garden notes, memory, observation, and the lived reality of illness and activism.

- The Garden (film): a fiercely imaginative work tied to the landscape around Prospect Cottage, blending politics, dream logic, and tenderness.

- Blue (film): an essential late workminimal in visuals, immense in feelingoften discussed alongside his final years and the urgency of bearing witness.

Read or watch these and the garden stops being a “cool location” and becomes what it really is: a practiceof seeing, of making, of refusing to disappear.

Experiences: What Derek Jarman’s Garden Feels Like (A 500-Word Immersion)

Imagine walking toward Prospect Cottage with the wind doing what wind does best: acting like it owns the place. The shingle under your feet shifts and clicks, a sound that’s half music, half reminder that you’re not on a friendly, padded path. The horizon is wide and blunt. The air tastes faintly of salt. And thenthere it is: the black cottage with its bright yellow trim, looking both cheerful and defiant, like it dressed for a storm on purpose.

What visitors often describe first is the light. Dungeness light doesn’t behave like polite city light. It arrives full-volume, bouncing off stone and sea and sky, making colors feel louder than they should. Even the plants seem to register itpoppies flashing like small sparks, silvery foliage catching brightness, shadows cut sharp around rocks and driftwood. In that kind of light, “minimalism” stops meaning empty and starts meaning exact.

Then you notice the objects. Stones arranged in circles and lines. Driftwood placed like sculpture. Bits of weathered material that look accidental until you realize they’re not. The garden feels like it has grammar: repetition, pauses, emphasis. You start reading it the way you read a poemby noticing patterns and letting meaning arrive slowly. It’s a space that rewards you for paying attention, which is basically the opposite of the internet.

The second experience people talk about is the sense that the garden doesn’t “end.” There isn’t a clean boundary where nature stops and design starts. The shingle continues outward and the view includes everythingsea, sky, and yes, that looming industrial silhouette in the distance. The presence of the power station is unsettling, but it also sharpens the point: this isn’t a fantasy landscape. It’s a real one, with real threats, and the garden exists inside that reality without surrendering to it.

The emotional temperature shifts depending on what you bring with you. If you show up expecting an Instagram-perfect garden, you may feel briefly confusedlike someone handed you a masterpiece on a paper plate. If you show up expecting meaning, you’ll feel it everywhere: in the stubbornness of plants thriving in harsh conditions, in the careful placement of stones, in the way the cottage faces outward like it’s still keeping watch. For many people, the garden feels like a conversation with timeabout fragility, endurance, and the daily choice to make something beautiful even when the world is not cooperating.

And here’s the strangest part: for all its history and heaviness, the garden can feel uplifting. Not in a “everything is fine” waymore like a “you can still make things” way. You leave thinking about your own constraints: your own difficult corner, your own patch of metaphorical shingle. And you wonder what would happen if, instead of waiting for perfect conditions, you started placing stonesone deliberate, hopeful decision at a time.