Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The honest answer: no alcohol is “good” for your health

- What matters most: dose, frequency, and what you call “one drink”

- Why the “red wine is healthy” story won’t die (and what’s actually true)

- Alcohol’s biggest health trade-offs (in plain English)

- So… which alcohol is “best” if you choose to drink?

- What the newest U.S. dietary guidance says (and why it matters)

- Smart, lower-risk drinking habits (for adults who choose to drink)

- Who should avoid alcohol completely?

- If you want “the benefits,” skip the booze and keep the good parts

- Quick myth-busting FAQ

- Experiences People Commonly Report When They Rethink Alcohol (About )

- Conclusion

If you’ve ever heard someone say, “Red wine is basically salad,” you’ve met one of modern wellness culture’s most persistent rumors.

(Somewhere, a grape is blushing.) The truth is more complicatedand more importantthan a catchy toast.

This article breaks down what the best U.S. health sources have been saying lately: what alcohol actually does in the body, why the

“healthy drink” idea is shaky, andif an adult chooses to drink anywaywhat choices are generally lower risk.

Spoiler: the healthiest alcohol for your body is a lot like the healthiest donut… it’s mostly about how often, how much, and what else comes with it.

The honest answer: no alcohol is “good” for your health

Ethanol (the type of alcohol in beer, wine, and spirits) is the active ingredientand it’s not a vitamin. U.S. public health agencies

are clear that alcohol is linked to increased cancer risk, and that risk can rise even at low levels for certain cancers.

In January 2025, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory highlighted a causal link between alcohol consumption and increased risk for

at least seven cancer types (including breast, colorectal, esophagus, liver, mouth, throat, and voice box).

And when it comes to heart health, the American Heart Association says it does not recommend drinking wine (or any alcohol)

to gain potential health benefits, noting that any observed “benefits” in older studies may reflect lifestyle differences rather than alcohol itself.

So if you’re searching for the “healthiest alcohol,” the most evidence-based framing is:

no type of alcohol improves health overallbut some drinking patterns and drink choices are less risky than others.

What matters most: dose, frequency, and what you call “one drink”

What is a “standard drink” in the U.S.?

Many people pour “a glass” without realizing they’ve made a science experiment. In the United States, a standard drink contains about

14 grams (0.6 fl oz) of pure alcohol.

- Beer: 12 oz at ~5% ABV

- Wine: 5 oz at ~12% ABV

- Spirits: 1.5 oz (“a shot”) at 80-proof (40% ABV)

Higher ABV = more alcohol per pour. A 12 oz “craft” beer at 9–10% can easily count as ~2 standard drinks.

What counts as “excessive” alcohol use?

The CDC defines binge drinking as 4+ drinks for women or 5+ drinks for men on one occasion, and heavy drinking as

8+ drinks/week for women or 15+ drinks/week for men. The CDC also explicitly includes underage drinking

(any alcohol under 21) as excessive alcohol use.

Why the “red wine is healthy” story won’t die (and what’s actually true)

The red wine myth usually leans on two ideas:

- Wine contains polyphenols (like resveratrol), which can have antioxidant/anti-inflammatory effects in lab settings.

- Some older observational studies linked light-to-moderate drinking with fewer heart events.

The catch: antioxidants aren’t exclusive to wine (grapes, berries, peanuts, and many plants bring them without ethanol),

and “moderate drinkers” in older studies often differed in major ways (diet quality, income, exercise, social support, access to healthcare).

Newer discussions from major health institutions emphasize that cause-and-effect is not proven and that alcohol carries real risks.

Translation: you can get the “Mediterranean vibe” without turning your liver into a customer service desk.

Alcohol’s biggest health trade-offs (in plain English)

1) Cancer risk: type matters less than amount

Multiple U.S. sources emphasize that all types of alcoholic drinks are linked to increased cancer risk, and that

the amount over time is a key drivernot whether it’s beer, wine, or spirits.

2) Heart health: “maybe a little benefit” is not a free pass

Alcohol can raise blood pressure and is linked to rhythm problems like atrial fibrillation at higher intakes.

Even when some studies suggest a small benefit at very low levels for certain outcomes, health organizations do not advise starting to drink

for heart protectionbecause the overall risk profile (especially cancer) doesn’t disappear.

3) Sleep, mood, and “why do I feel 57 years old today?”

Alcohol may make you sleepy at first, but it often worsens sleep quality later in the night. Poor sleep can then nudge appetite,

anxiety, and concentration in the wrong direction. Many people don’t connect “one drink to unwind” with “why I’m tired all week”

until they take a break and notice the difference.

4) Calories: alcohol is sneaky energy

Alcohol provides calories with little nutritional value, and mixers can turn a drink into dessert-with-a-side-of-regret.

For example, MedlinePlus lists approximate calories for standard servings:

regular beer (~153), light beer (~103), and 80-proof spirits (about ~97 per 1.5 oz).

So… which alcohol is “best” if you choose to drink?

First, two non-negotiables:

- If you’re under 21: the healthiest choice is none. Underage drinking is categorized as harmful by U.S. public health guidance.

- If you don’t drink now: don’t start “for health.” Major heart and cancer guidance does not recommend that.

If you are an adult of legal drinking age and still want a realistic answer, here it is:

the lowest-risk choice is the drink that helps you drink less alcohol overall.

Since the drink “type” matters less than dose, “healthiest” really means:

lower alcohol per serving, fewer added sugars, and easier portion control.

Lower-risk picks (generally) for adults who drink

-

Lower-ABV beer (or a true 12 oz serving):

Easier to sip slowly and track. Watch ABVsome “one can” beers are really 1.5–2 drinks. -

Dry wine in a measured pour (5 oz):

If wine is your thing, a smaller, measured serving helps keep it from becoming “oops, that was half a bottle.” -

Spirits + zero-sugar mixer (club soda/seltzer) in a measured pour (1.5 oz):

Spirits can be lower-calorie per standard serving than many sugary cocktails, but only if the pour is measured and the mixer isn’t sweet. -

Champagne/sparkling wine (small pour):

Often served in smaller volumes, which can help portion controlagain, measure and pace.

Higher-risk “health halo” traps

- Sugary cocktails (lots of syrup/juice/cream): easy to overconsume calories and alcohol.

- High-ABV craft beers: delicious, but a “single” can may equal multiple drinks.

- “Clean” tequila/vodka myths: ethanol is ethanol; “clean” usually means “great marketing.”

- Energy drink + alcohol: risky combo for safety and overconsumption.

What the newest U.S. dietary guidance says (and why it matters)

The U.S. Dietary Guidelines have traditionally provided numeric daily limits, but the newly released

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030 emphasize a simpler message:

consume less alcohol for better overall health.

The 2025–2030 document also lists groups who should avoid alcohol completely, including pregnant women, people recovering from alcohol use disorder

(or unable to control intake), and people taking medications or with medical conditions that interact with alcohol.

Practical takeaway: if you drink, treat alcohol like dessertoptional, not “health food,” and best kept small.

Smart, lower-risk drinking habits (for adults who choose to drink)

1) Decide your “number” before the first sip

Your future self is not an unbiased decision-maker. Pick a limit in advance (for example, 1 standard drink),

then stop when you hit itbefore “one more” becomes “why is my phone in the fridge?”

2) Measure at home; ask for smaller pours when out

A “generous pour” can quietly double the alcohol. Knowing what a standard drink looks like helps you stay honest.

3) Slow down and alternate with water

Pacing lowers the chance you’ll drift into binge territory (and the regret zone). The CDC’s binge thresholds exist for a reason.

4) Never “save calories” by skipping food

Drinking on an empty stomach often leads to faster intoxication and worse choicesboth in drinks and in late-night “creative cuisine.”

5) Build alcohol-free days into your week

Regular breaks reduce overall exposure and help you notice how alcohol affects your sleep, anxiety, training, skin, and appetite.

Who should avoid alcohol completely?

- Anyone under 21 (U.S. legal age; also listed by CDC as a harmful drinking category).

- Pregnant (or trying to become pregnant).

- People who can’t control how much they drink or are in recovery.

- People with certain medical conditions (e.g., liver disease, pancreatitis) or who take medications that interact with alcohol.

- Anyone with a personal or strong family history of alcohol use disorder (extra caution is explicitly noted in dietary guidance).

If you want “the benefits,” skip the booze and keep the good parts

For heart health

Do the things that actually have a strong track record: more fiber, more plants, better sleep, regular movement,

stress management, and not smoking. The AHA’s stance is clear: don’t drink alcohol for health benefits.

For “red wine antioxidants”

Eat grapes, berries, peanuts, and colorful plants. You’ll get polyphenols without the ethanol and added risk.

For relaxation/social connection

Keep the ritual: fancy glass, citrus twist, music, friendsjust swap the ethanol. Try seltzer with bitters, a

“mocktail” built on tea, or a non-alcoholic beer/wine (check sugar and calories).

Quick myth-busting FAQ

Is red wine healthier than beer or liquor?

Not in a way that cancels alcohol’s risks. Major cancer guidance emphasizes that all alcohol types increase cancer risk,

and that the amount over time matters most.

Is tequila the “cleanest” alcohol?

“Clean” usually refers to fewer sugary mixers or smaller portionsnot a special protective effect. Ethanol is still ethanol.

If I only drink on weekends, I’m fineright?

Weekend-only can still be risky if it becomes binge drinking. The CDC binge thresholds (4+ for women, 5+ for men in one occasion)

are a useful reality check.

What’s the “healthiest” cocktail?

One that’s small, measured, and low in added sugarthink a 1.5 oz spirit with club soda and citrus, or a wine spritzer with a true 5 oz pour.

But “healthiest” here means “less risky,” not “good for you.”

Experiences People Commonly Report When They Rethink Alcohol (About )

I don’t have personal experiences, but there are patterns people commonly describe when they experiment with alcohol and notice what changes.

Think of these as “realistic, frequently reported scenarios” rather than a one-size-fits-all promisebecause bodies, genetics, and lifestyles vary a lot.

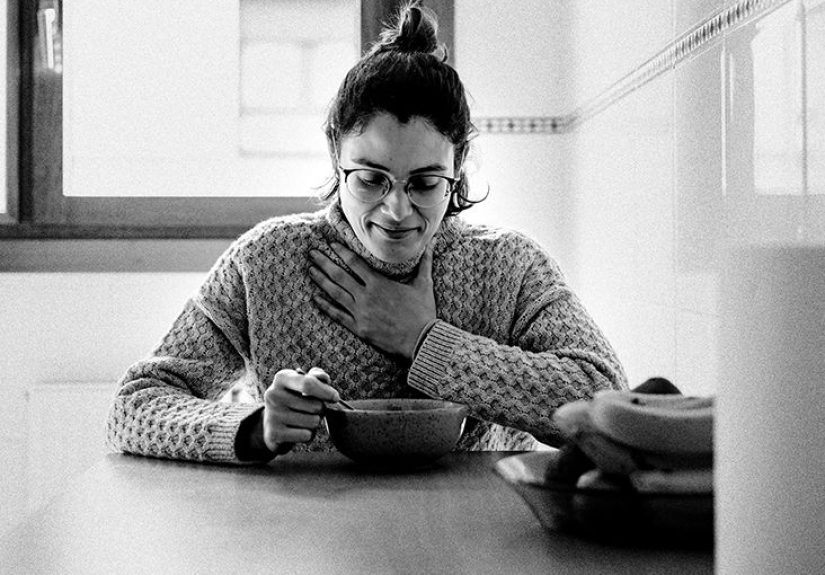

Experience #1: “The nightly glass of wine” surprise

Many adults start with a routine that looks harmless: one glass of wine after dinner to unwind. It feels civilized. It pairs well with streaming.

It also quietly becomes a habit loopstress → pour → relief.

When people take a 2–4 week break, they often report two surprises. First: sleep feels different. They fall asleep a bit more naturally, wake up

fewer times, and feel less “foggy” in the morning. Second: cravings change. Without alcohol’s appetite-stirring effect and late-night snacking,

they notice fewer “kitchen encore” moments.

The most interesting part is psychological: some people realize the drink wasn’t the relaxationthe ritual was. A glass, a pause,

a boundary between “work brain” and “home brain.” When they rebuild the ritual with tea, sparkling water, or a mocktail, they keep the comfort

but lose the next-day drag.

Experience #2: The “weekend warrior” reality check

Another common story is weekend-only drinking: no alcohol Monday through Thursday, then a big Friday or Saturday night. People often see this as

“balance,” but the body experiences it as a spike. If that spike crosses binge thresholds, it can come with poor sleep, higher anxiety the next day,

and a noticeable hit to workouts or energy on Sunday.

When people cut the peak (for example, two drinks instead of five) and extend the pacing (water between drinks, slower sipping, food first),

they often describe a “best of both worlds” shift: still social, still celebratory, but fewer consequences. The win isn’t moralit’s practical:

fewer arguments, fewer impulse purchases, fewer texts that start with, “Soooo about last night…”

Experience #3: The “I only drink ‘healthy’ alcohol” myth

Some people try to optimize alcohol the way they optimize protein: “I’ll do red wine for antioxidants,” or “tequila is clean,” or “I’ll only drink

low-carb seltzers.” What they often learn is that the label matters less than the total ethanol and the pattern. A “clean” drink can still be a large

pour, or it can turn into three drinks because it goes down easily.

The most helpful shift people report is moving from “Which alcohol is healthiest?” to “What is my lowest-risk way to drinkif I drink at all?”

That question leads to measurable pours, fewer drinking days, less added sugar, and a bigger focus on sleep and recovery.

Bottom line: for adults who choose alcohol, the most “health-supportive” change usually isn’t switching from beer to wineit’s drinking less often,

drinking smaller amounts, and keeping the ritual without depending on the ethanol.

Conclusion

If you came here hoping for a single hero drink that upgrades your health, science is a bit of a party pooper: alcohol isn’t “good” for you.

Public health guidance increasingly emphasizes that less is better, and cancer risk rises with alcohol intake over time.

If you’re an adult and still decide to drink, the lowest-risk approach is boringbut effective: keep servings standard, choose lower-sugar options,

avoid binge patterns, and take alcohol-free days. Your body doesn’t care if it’s “fancy wine” or “top-shelf tequila”it counts ethanol.