Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What People Really Mean by “Build a Cutting Laser From an Old PC”

- Why DIY “Cutting Lasers” Are High-Risk (Even If You’re Careful)

- If You Want the “Old PC + Laser Cutter” Dream, Here’s the Safe Way to Do It

- A Laser Cutter Safety Checklist (For Real Life, Not Internet Bravado)

- How to “Harvest” an Old PC for Maker Projects Without Doing Anything Sketchy

- Cost & Reality Check: What You’re Actually Buying When You Buy “Laser Capability”

- Conclusion: Make the Old PC the Smart Part of the Setup

- Experiences & Lessons Makers Share (An Extra )

Quick safety reality check: A “cutting laser” isn’t a cute weekend craft. A true cutting-capable laser system is powerful enough to permanently injure eyes and skin, start fires, and produce hazardous fumes if you process the wrong materials. Because of that, I’m not going to give step-by-step instructions, wiring diagrams, or a parts list for making a cutting laser from computer scrap.

What I can do (and what this article does) is explain what people usually mean by “build a cutting laser from an old PC,” why the PC is the easy part, what makes laser cutting risky, and how to repurpose an old PC into a safe, legitimate, still-cool laser-adjacent maker setupwithout turning your workspace into a “before” photo for an insurance commercial.

What People Really Mean by “Build a Cutting Laser From an Old PC”

Let’s translate the headline into reality. The old PC is rarely the laser. It’s the brain (or at least the assistant manager) that runs design files, sends motion commands, logs settings, and makes the machine feel like a modern tool instead of a mysterious box that hums at you.

A cutting laser system usually includes:

- A laser source (diode, CO₂, or fiber in many commercial setups)

- Motion hardware (gantry/linear rails or a galvo head, plus motors and drivers)

- Optics and beam path control (mirrors/lenses depending on the laser type)

- A protective enclosure (not optional if you want to keep your eyesight)

- Interlocks and controls (to prevent operation when open/unsafe)

- Ventilation/fume extraction (because burning stuff indoors is… still burning stuff indoors)

- Software workflow (design → export → job setup → run → document)

The old PC can be a great fit for the software side: design apps, job control, file storage, and even a dedicated “shop computer” that lives with the machine so you’re not balancing a laptop next to smoke and dust like you’re speedrunning regret.

Why DIY “Cutting Lasers” Are High-Risk (Even If You’re Careful)

Laser hazards aren’t just “don’t look into the beam.” They’re more like a layered cake of “wow, I didn’t realize that could happen.” In workplace safety guidance, eye injury is repeatedly treated as the top concern, and higher hazard classes mean higher potential for serious harm.

Laser classes: why cutting typically lives in the danger neighborhood

In the U.S., laser products are commonly categorized into hazard classes. Higher classes generally mean greater risk of injury and stricter control requirements. Cutting-capable setups often involve lasers in higher hazard categories, which is one reason commercial machines lean heavily on enclosures, interlocks, labels, and controlled operation.

One key concept: a powerful laser can be made safer for users when it’s built into a fully enclosed system designed so that hazardous radiation isn’t accessible during normal operation. That’s why many consumer-friendly machines aim for an enclosed product-style approach rather than “open beam on a table.”

Reflections are the plot twist

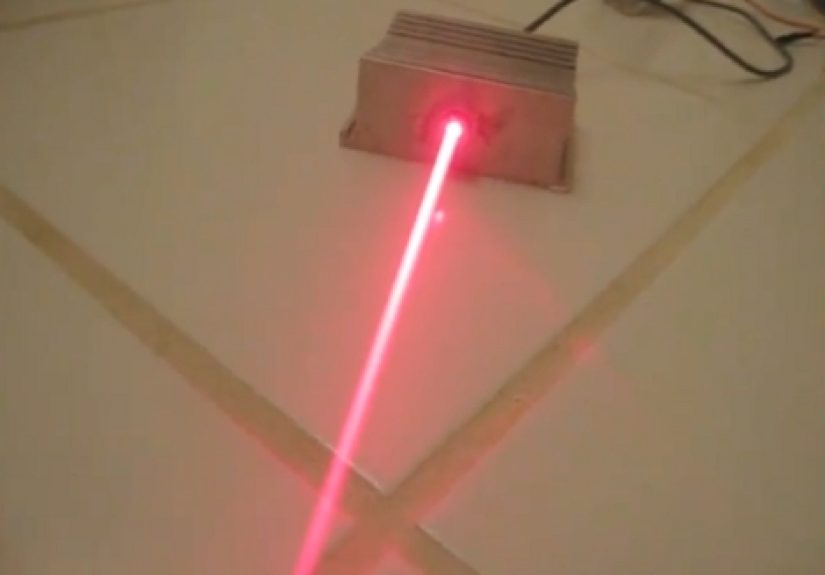

People imagine a laser as a straight line: point it down, it does its job, end of story. Real life includes reflections, shiny surfaces, unexpected angles, and materials that behave differently than your “test scrap” did. This is where “I was being careful” can still fail, because physics doesn’t care about your confidence.

Fire risk is not hypothetical

Laser cutting is literally concentrated heat. Some materials ignite, smolder, or flare up if airflow shifts, resin pockets show up, or residue accumulates. Institutional safety programs for laser cutters often treat fire as a primary hazard alongside beam exposure and air contaminants.

Fumes: the part people underestimate until their nose complains

Laser processing can create airborne contaminantsfine particulates and volatile compoundsdepending on the material and settings. That’s why universities, industrial hygiene programs, and workplace safety evaluations emphasize local exhaust ventilation and good air handling practices.

And yes, there are materials that are famous for being “do not laser” because they can release highly corrosive or toxic gases. PVC gets singled out often for exactly that reason. If you’ve ever wondered why experienced makers get dramatic about it, it’s because the consequences can be serious.

If You Want the “Old PC + Laser Cutter” Dream, Here’s the Safe Way to Do It

Here’s the good news: you can absolutely use an old PC as the backbone of a laser cutting workflowjust pair it with a certified, enclosed laser system or a makerspace machine designed with proper engineering controls.

Option 1: Turn the old PC into a dedicated laser workstation

Think of this as giving your old computer a new career: “Shop Computer, Laser Division.” The goal is reliability and convenience, not gaming benchmarks.

Practical workstation setup ideas:

- Clean OS install with only the tools you need (design, job prep, file transfer)

- Offline-by-default approach (reduces update surprises mid-project)

- Project library organized by material, thickness, and date

- Calibrated monitor if color/graphics work matters (especially for engraving art)

- External storage for backups (because “I’ll remember where I saved it” is a myth)

Option 2: Use your PC with an enclosed “embedded” laser product

If you’re buying or using a laser cutter, prioritize machines designed as enclosed systems with safety features that prevent accessible hazardous radiation during normal operation. Look for things that safety programs commonly emphasize, such as protective housings, interlocks, and clear labeling.

Translation: if the machine’s safety plan is “just don’t be dumb,” that’s not a plan. If it’s “the machine prevents exposure unless multiple safeguards fail,” you’re in a better place.

Option 3: Use the old PC for non-laser cutting/plotting projects (still awesome, way safer)

If your main motivation is “make a machine from scrap,” there are safer builds that scratch the same itch:

- Vinyl cutting workflow (design → cut → weed → apply)

- Pen plotter art (generative designs, cards, posters)

- CNC drawing/foam cutting with safe tooling (depending on the setup)

- 3D printer controller station (slicing, monitoring, documentation)

You still get the “repurpose the PC” satisfaction, plus you keep your eyebrows and your vision. Everybody wins.

A Laser Cutter Safety Checklist (For Real Life, Not Internet Bravado)

If you’re operating a laser cutterat school, a makerspace, or a workshopthese practices are common across safety guidance and institutional programs:

Engineering controls first

- Enclosure/protective housing that keeps the beam contained

- Interlocks so the laser can’t run when access panels/doors are open

- Key control / authorized operation to prevent casual misuse

- Warning labels and signage appropriate to the hazard class

Air quality and ventilation are not optional

- Use local exhaust ventilation to capture contaminants near the source

- Don’t cut mystery materialsidentify them first

- Avoid known high-risk plastics (PVC is a classic “no” for many laser environments)

Fire prevention is part of the job

- Never leave a running laser unattended (seriouslythis is one of the biggest practical rules)

- Keep the bed and exhaust path clean so residue doesn’t become fuel

- Have the right fire response plan for your space (not just vibes)

How to “Harvest” an Old PC for Maker Projects Without Doing Anything Sketchy

Repurposing an old PC is one of the best maker moves because it’s cheap, reliable, and keeps e-waste out of the trash pile. Safe reuse ideas that don’t involve building a dangerous laser:

Best parts of an old PC to reuse

- Case (can become a shop-safe enclosure for electronics projects)

- Power supply (use only in appropriate low-risk electronics contextsdon’t improvise)

- Fans (great for ventilation experiments and filtered enclosures)

- Storage drives (project archives, design libraries)

- USB peripherals (keyboards/mice/monitors for a dedicated workstation)

If you’re dismantling a PC, treat it like electronics work: unplug it, discharge safely, and dispose of components responsibly through e-waste programs. The goal is “creative reuse,” not “surprise sparks.”

Cost & Reality Check: What You’re Actually Buying When You Buy “Laser Capability”

People fixate on the laser module like it’s the whole story. In practice, the “laser capability” you’re paying for is:

- Safety engineering (enclosure, interlocks, labeling, controls)

- Reliable motion accuracy (repeatable cuts, consistent results)

- Fume management (extraction, filtration options, ducting support)

- Support and documentation (settings guidance, maintenance schedules)

That’s why a safe, enclosed system costs more than “a powerful light and some rails.” You’re paying for the parts that keep a tool from becoming a hazard.

Conclusion: Make the Old PC the Smart Part of the Setup

So, can you “build a cutting laser from an old PC”? The honest answer is that the PC can absolutely be part of a laser cutting setupbut the cutting laser portion is not a safe DIY-from-scrap project. The smarter move is to repurpose your old PC as a dedicated workstation for a properly enclosed laser cutter (or a makerspace machine), where the safety controls are designed in from day one.

If what you really want is the maker thrillturning junk into a toolyour old PC can still be the hero. Just let it run the workflow, manage the files, and power the creativity… while the laser part stays in the hands of equipment built to keep humans intact.

Experiences & Lessons Makers Share (An Extra )

Ask a group of makers about lasers and you’ll get two types of stories: the fun ones (“I made a perfectly fitting box on the first try!”) and the cautionary ones (“I learned why you never walk away from a running job”). The interesting part is how often the lessons aren’t about the beamthey’re about everything around it.

Lesson #1: The smell is a diagnostic tool. People talk about laser fumes like they’re just “a little smoky.” In reality, a weird odor can be your first signal that you’re processing the wrong material or that your ventilation isn’t capturing enough at the source. In maker spaces with good safety culture, you’ll see people pause a job, check material labels, and make sure the exhaust is actually pulling. The “tough it out” approach tends to disappear after you’ve spent a few minutes in a room that smells like burnt mystery plastic.

Lesson #2: Organization is safety. A dedicated old-PC workstation sounds like a convenience upgrade, but it’s also a safety upgrade. When your job files, notes, and settings are organized, you’re less likely to guess. Makers who document what worked (material type, thickness, results, and any issues) build a personal “settings library” over time. That reduces trial-and-error, which reduces the chance of overheating, flare-ups, or ruining parts. In other words, a neat folder structure can be as protective as any fancy gadgetbecause it keeps you from improvising under pressure.

Lesson #3: Fire happens fast. The classic near-miss story is someone who looked away “just for a second.” Sometimes it’s to answer a message. Sometimes it’s to grab another sheet of material. Then they glance back and see a flare-up or a small sustained flame. Even when it’s contained, it’s a reminder that laser cutting is an active process, not a passive print job. The makers who run lasers the longest tend to treat the machine like a stovetop: you don’t leave the kitchen while something is cooking.

Lesson #4: The safest laser is the one that won’t run unless it’s safe. People often think safety is about personal disciplinewearing the right PPE, paying attention, following rules. That matters. But experienced operators love engineering controls because they reduce the number of ways a momentary mistake can become permanent. Door interlocks, protective housings, key controls, and clear labels are boring… until the day they prevent an accident. That’s why institutional laser cutter policies can feel strict: they’re built from hard-earned experience.

Lesson #5: The “old PC” is an underrated upgrade. Makers who set up an older desktop as a dedicated shop computer often report the same unexpected benefit: their workflow becomes calmer. No juggling files between devices. No frantic searching for the “final-final-v3” version of a design. No doing machine control from a laptop balanced on a dusty workbench. The PC becomes the stable home basewhere you design, queue jobs, document results, and keep a clean record of what you did. And that stable workflow is exactly what you want around a tool that rewards preparation and punishes randomness.

In the end, the most satisfying “build” might not be a dangerous DIY laser at all. It might be building a system: an organized workstation, safe equipment, good ventilation, and habits that make every project smoother. The old PC can be the anchor of that systemquietly proving that yesterday’s tech can still power today’s creativity.