Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick refresher: what CPP is (and what it isn’t)

- Complication #1: Reduced adult height (the growth plates close early)

- Complication #2: Earlier menstruation and other early pubertal milestones

- Complication #3: Social and emotional ripple effects

- Complication #4: Missing an underlying medical cause

- Complication #5: Longer-term health associations (what we know, and what we don’t)

- Complications related to evaluation

- Complications related to treatment (and what side effects can happen)

- How clinicians work to prevent complications

- When to seek urgent medical advice

- Bottom line

- Experiences related to CPP complications (what families often report)

- SEO Tags

Central precocious puberty (CPP) is one of those medical phrases that sounds like a spaceship malfunction, but it’s actually about timingspecifically,

puberty starting earlier than expected because the brain flips the “go” switch too soon.

For many families, the first clue is simple: “Why is my second-grader suddenly growing like a teenager… and why do I need to buy deodorant in bulk?”

The good news: CPP is treatable, and many kids do very well. The tricky part is that early puberty can come with real complicationssome physical,

some emotional, some related to missing an underlying condition if CPP isn’t evaluated properly.

Let’s break down what the complications are, why they happen, and how clinicians work to prevent them.

Quick refresher: what CPP is (and what it isn’t)

CPP means puberty starts early because the hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal axis (the brain’s hormone command center) activates sooner than usual.

In practical terms, the body follows the same general puberty sequence as it would laterjust on an earlier calendar.

CPP is different from peripheral precocious puberty, where puberty-like changes come from hormone production outside the brain’s usual control

(for example, from adrenal or gonadal sources). It’s also different from “benign variants” like isolated early breast development or early pubic hair that

don’t progress in a typical puberty pattern.

A key point: early changes aren’t automatically an emergency. But progressionrapid growth, advancing pubertal stages, or a big jump in bone agecan

raise the risk of complications and is a major reason clinicians take possible CPP seriously.

Complication #1: Reduced adult height (the growth plates close early)

Why it happens

Puberty hormones don’t just change the body’s appearance; they also accelerate bone maturation. Kids with CPP often grow quickly at first and may even be taller than peers.

But that early growth comes with a catch: the growth plates (epiphyses) can fuse sooner, cutting the growth window short.

Think of it like getting a head start in a race… then being told you have to stop running earlier than everyone else.

What it can look like in real life

Imagine an 7-year-old who shoots up in height over six months, jumps clothing sizes, and suddenly looks older than classmates.

Their pediatrician checks a bone-age X-ray, and it shows bones maturing several years ahead of chronological age.

Without treatment (when treatment is appropriate), that child might end up shorter as an adult than their genetics predicteddespite being “tall for their age” right now.

Why this matters beyond the number on the measuring tape

Height itself isn’t a “good” or “bad” outcome. The bigger issue is that a substantial loss of predicted adult height can be a lifelong consequence of untreated, progressing CPP.

This is one of the most common reasons families are referred to pediatric endocrinology and why treatment is considered when puberty is clearly advancing.

Complication #2: Earlier menstruation and other early pubertal milestones

In CPP, pubertal milestones may occur years earlier than expected. For some girls, this can include menstrual bleeding at an unusually young age.

Even when medically uncomplicated, early menstruation can create practical and emotional challenges:

managing periods at school, handling cramps, and dealing with a body that’s developing out of sync with peers.

For boys, early puberty may involve rapid progression of pubertal development and a strong growth spurt at a young age.

The complication isn’t simply “puberty happened,” but that puberty may unfold before a child is socially and emotionally ready.

Complication #3: Social and emotional ripple effects

Feeling “different” can be its own complication

A child with CPP may look older than classmates, get treated as older by adults, or feel singled outsometimes without understanding why.

Kids can face teasing, awkward questions, or unwanted attention, and parents can feel like they’re parenting on “hard mode” overnight.

Possible mental health impacts

Research and clinical experience suggest early puberty can be associated with increased stress, anxiety, mood changes, and behavioral challenges for some kids.

Not every child struggles, and many do just fineespecially with supportive adults and good coping strategies.

But it’s important to treat psychosocial well-being as a real part of care, not an afterthought.

School-life complications

“Complications” can be surprisingly practical: a kid needing deodorant, bras, or period supplies earlier than expected; gym class discomfort; uniforms that suddenly don’t fit;

and the emotional fatigue of explaining body changes when you’d rather be thinking about Pokémon or soccer.

Complication #4: Missing an underlying medical cause

One of the most serious “complications” of CPP isn’t caused by puberty itselfit’s the risk of overlooking what triggered puberty early.

Many cases (especially in girls) are idiopathic, meaning no clear cause is found. But CPP can also be linked to conditions involving the central nervous system.

Why clinicians may consider brain imaging

The likelihood of an identifiable underlying cause is generally higher in boys and in very young children with CPP.

Because of that, pediatric endocrinologists often consider brain MRI in certain scenariosespecially in boys, younger girls, or when neurological symptoms are present.

The goal is straightforward: if there’s something treatable behind the scenes, you want to find it early.

Red flags that raise concern

While many children with CPP have no neurological symptoms, clinicians become more alert when early puberty is accompanied by headaches,

vision changes, seizures, or other neurologic signsbecause those symptoms can signal an issue that needs prompt evaluation.

Complication #5: Longer-term health associations (what we know, and what we don’t)

Puberty timing has been studied as a “marker” for later health risks, especially in girls.

Earlier pubertal timing (including early menarche) has been associated in population studies with higher risks of adult obesity, insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes,

and cardiovascular disease outcomes. Some studies also link earlier thelarche/menarche with higher breast cancer risk later in life.

Here’s the nuance: association doesn’t always mean direct causation. Body weight, genetics, environment, and social factors can influence both early puberty and later health.

Still, these associations matter because CPP can trigger early menarche and earlier hormone exposure. Clinicians often use this information as motivation for

healthy lifestyle support (sleep, movement, nutrition, mental health), without blaming kids’ bodies or turning health into a morality contest.

Complications related to evaluation

Bone age and growth prediction can be stressful (and imperfect)

A bone-age X-ray is a common part of evaluating possible CPP. It helps estimate how mature the bones are and can assist in predicting adult height potential.

But predictions aren’t destiny. They’re best viewed as a planning tooluseful, but not a crystal ball.

Lab testing and stimulation tests

Diagnosing CPP may involve measuring puberty-related hormones and sometimes using a stimulation test to confirm activation of the brain-driven puberty pathway.

For kids, the complication here is often emotional: fear of needles, anxiety about results, and the feeling that their body is being “graded.”

A calm, child-friendly care team makes a huge difference.

Complications related to treatment (and what side effects can happen)

The main treatment: GnRH agonist therapy

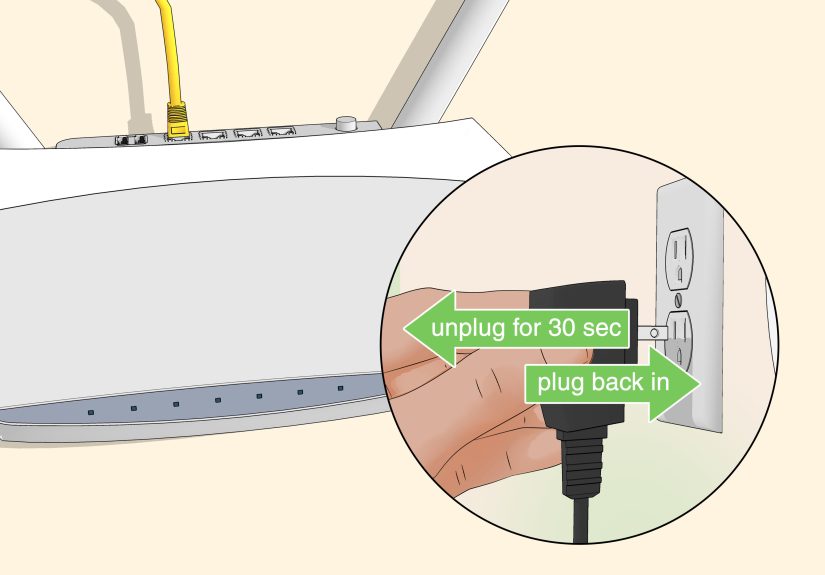

When CPP is clearly progressive and treatment is appropriate, the standard approach is a medication called a GnRH agonist.

These medicines pause the pubertal hormone cascade by desensitizing the pituitary response, effectively putting puberty “on hold” for a while.

The goals are usually to protect adult height potential and ease psychosocial strain when puberty is arriving far too early.

Common, short-term side effects

Side effects are often related to the delivery method (injections or implants). Kids may have injection-site pain, redness, swelling, or irritation.

With implants, there can be discomfort around insertion or removal and the usual minor-procedure hassles.

Less common treatment complications

Rarely, children can develop a sterile abscess at an injection site (an inflammatory reaction without infection).

Some kids experience headaches or hot-flash-like symptoms. Weight changes can happen during treatment, although the relationship between CPP, treatment, and weight is complex:

some children with CPP already have higher BMI, and many factors affect weight over time.

Bone density, fertility, and “Will this mess up the future?”

A common parent worry is whether pausing puberty affects long-term reproductive health. Overall, available data and decades of clinical use support that

GnRH agonist treatment for CPP is effective and generally considered safe, with puberty typically resuming after treatment stops.

Clinicians monitor growth patterns, bone age, and overall well-being during therapy to keep benefits high and risks low.

How clinicians work to prevent complications

1) Confirm the diagnosis (because not all early changes are CPP)

Avoiding overtreatment matters. Some children have early signs that do not progress or represent a normal variation.

Careful tracking over timegrowth velocity, pubertal staging, and bone age changeshelps clinicians distinguish CPP from non-progressive variants.

2) Focus on growth outcomes that matter

Treatment decisions often weigh the child’s age, rate of progression, bone-age advancement, predicted adult height, and family concerns.

If puberty is racing ahead and height potential is dropping, that strengthens the case for intervention.

3) Support mental health like it’s part of the endocrine system (because it is)

Practical supports can reduce psychosocial complications:

preparing a child for body changes in age-appropriate language, coordinating with school nurses, normalizing emotions, andwhen neededconnecting with counseling.

The goal isn’t to make kids “tougher,” but to make their environment kinder.

4) Keep an eye on overall health

Clinicians often encourage healthy routines that support both physical and emotional resilience:

consistent sleep, regular movement, balanced meals, and stress management.

This is about well-being and developmentnot dieting, body shaming, or chasing an “ideal” shape.

When to seek urgent medical advice

Contact a clinician promptly if early puberty is paired with concerning symptoms such as persistent or severe headaches, vision changes, vomiting,

seizures, or other neurologic signs. Also seek advice if puberty changes are progressing rapidly or if a child is distressed, anxious, or struggling at school.

Bottom line

CPP isn’t just “puberty, but early.” Its complications can include reduced adult height due to early growth plate fusion, early pubertal milestones that create practical challenges,

psychosocial stress, andmost importantlythe risk of missing an underlying cause if evaluation is delayed.

The best outcomes usually come from timely recognition, thoughtful diagnosis, and individualized treatment that supports both body and mind.

Experiences related to CPP complications (what families often report)

Families often describe the beginning of CPP as a slow realization followed by a fast sprint. At first, it can look like ordinary growth:

“They’re eating more,” “They’re taller,” “Maybe they just got my side of the family genetics.” Then the clues pile uprapid height changes,

body odor that arrives like it owns the place, acne that shows up without an invitation, and emotions that feel bigger and harder to predict.

Parents sometimes say the hardest part isn’t any single symptomit’s the feeling that childhood is being rushed by an invisible schedule.

One common “complication” families talk about is social mismatch. A child may look older and get treated older, even though their brain is still very much the age it is.

Adults might expect more maturity, classmates might tease or ask personal questions, and the child may feel uncomfortable being noticed.

Some parents describe school mornings becoming more complicated: choosing clothes that feel comfortable, navigating gym class,

or having to plan for hygiene needs earlier than they ever expected. Kids may become more self-conscious, especially if their development is noticeable in a classroom of peers

who aren’t changing yet.

Another common experience is the emotional load around testing and appointments. Blood draws, stimulation tests, X-rays for bone age, and possibly an MRI can be scary,

especially when the child doesn’t feel “sick.” Families often say it helps when clinicians explain the “why” in kid-friendly terms:

“We’re checking how fast your body is growing,” or “We’re making sure your brain’s hormone signals aren’t starting too early.”

Parents also report that the waitingwaiting for results, waiting for follow-up, waiting to see if changes progresscan be more stressful than the tests themselves.

When treatment is recommended, families often describe mixed feelings: relief that something can help, plus worry about side effects, injections, and what it means long-term.

Many families report that routines and predictability helpsetting a “shot day” ritual, celebrating bravery (without turning it into pressure),

and giving kids control over small choices (“Which arm?” “Music or no music?”). Some kids feel better once physical changes slow down,

especially if they were uncomfortable with attention or teasing. Others mainly benefit from the calm that comes when adults finally have a plan.

Over time, families frequently say the biggest improvements come from treating CPP as a whole-life issue, not just a hormone issue.

That might mean coordinating with a school nurse for supplies, talking with a counselor about body changes, or practicing responses to awkward questions.

It also often means reminding a childrepeatedlythat they didn’t do anything wrong and their body isn’t “weird.”

Families who feel supported usually describe the journey as manageable: not always easy, but less scary once they understand the goals

(protect growth, protect well-being, and check for underlying causes) and once the child feels safe, informed, and respected.