Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why the Gyro Stays Upright: The Physics Doing the Heavy Lifting

- Inside a Fighter Jet Attitude Indicator: Overbuilt on Purpose

- “Self-Destruct” in Avionics: What It Usually Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- From Spinning Metal to Beams of Light: The Evolution of Gyros

- Why This Matters Beyond Cool Teardown Videos

- Practical Takeaways: The “So What?” List

- Conclusion

- Experiences Related to “A Gyro Staying Upright” (Extra 500+ Words)

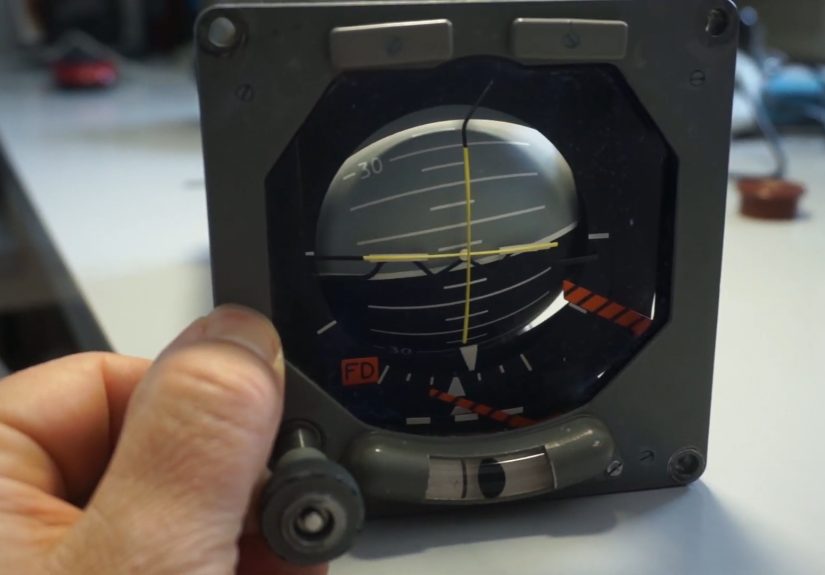

If you’ve ever watched a torn-down fighter jet attitude indicator (the “artificial horizon”) doing its thing, you’ve seen a small miracle of physics:

the instrument’s “horizon” stays stubbornly level even while everything around it gets jostled, rotated, and generally treated like a smoothie.

And in some military-grade units, after the show-and-tell is over, the device may literally protect itselfsometimes dramaticallyrather than be

easily reverse-engineered.

This article breaks down what’s really happening when a fighter jet gyro “stays upright,” why it self-corrects (most of the time), what “self-destruct”

can mean in the avionics world, and how modern aircraft moved from spinning metal to gyros made of light. We’ll keep it accurate, readable, and only

mildly nerdy (the fun kind of nerdy, like building a LEGO set with a torque wrench).

Why the Gyro Stays Upright: The Physics Doing the Heavy Lifting

Rigidity in space: the gyro’s superpower

A classic mechanical gyroscope is basically a rapidly spinning rotor. Once it’s spinning, it “wants” to keep its axis pointed the same way. This is

often described as rigidity in space: the gyro resists changes to its orientation because of angular momentum.

That’s the core reason the instrument can provide a stable reference. The airplane can pitch and roll, but the gyro tries to keep its own orientation.

In other words: the airplane moves around the gyro, not the other way around. (Your inner ear would like to file a complaint with HR at this point.)

Gimbals: letting the airplane move without dragging the gyro with it

The gyro in an attitude indicator is mounted in gimbalsthink of nested rings that allow rotation on multiple axes. The instrument case is bolted to the

aircraft and moves with it; the gyro assembly is suspended so it can remain stable while the case tilts around it.

The display you see is a clever translation: the “sky” and “ground” background is linked to the stabilized gyro reference, while the miniature airplane

symbol is tied to the instrument case. When the airplane banks left, the case banks leftso the miniature airplane banks left relative to the fixed

“horizon.” Your brain reads that instantly as “we’re banking left.” That’s not magic. That’s mechanical honesty.

Precession: the gyro’s annoying side quest

Here’s the catch: gyros don’t only resist movement. When a force is applied, a spinning gyro responds in a sideways way called precession.

In aviation, precession (plus friction and small imperfections) leads to drift and errors over time.

That’s why pilots learn to cross-check instruments. A gyro instrument is reliable in the moment, but it can slowly wander if you treat it like a forever-truth

machine. It’s more like a friend who gives great directionsuntil they confidently say, “I swear this is the right exit,” and you end up at a waffle house

in the next county.

Inside a Fighter Jet Attitude Indicator: Overbuilt on Purpose

Why fighter-grade instruments look like tiny industrial art

A fighter jet environment is brutally unfriendly: vibration, temperature swings, high-G maneuvers, and the expectation that everything works right now.

Even if a particular aircraft later adopts digital glass displays, legacy or specialized mechanical instruments were often designed like miniature tanks.

The result is hardware that looks “over-engineered” compared with a basic general aviation instrument. But in fighter aviation, “over-engineered” is often

just another way of saying “engineered to survive the real world.”

Self-erection and why “perfectly level” is a moving target

Many attitude indicators include an “erection” systeman internal mechanism that nudges the gyro back toward level relative to gravity. This helps recover

from small errors and keeps the display usable in normal flight. But it’s not a free lunch.

Training materials commonly note that some attitude indicators can slowly “correct” toward level even while you’re holding a steady bank. That means if you

stayed in a coordinated turn long enough, the instrument could start telling a very confident lie: “You’re level.” Not because it’s broken, but because it’s

designed to re-align with gravity over time and assumes most of your life is spent not doing ten-minute banked turns for fun.

Tumble limits and the “I have had enough” moment

Mechanical attitude indicators can also “tumble” if the aircraft exceeds certain pitch and bank angles or if the gyro is disturbed hard enough. When that happens,

the instrument may temporarily give unreliable indications until it settles back down.

This is one reason modern aircraft increasingly rely on solid-state attitude and heading reference systems (AHRS). But the mechanical versions are still

a masterclass in how to make physics usefulespecially when you don’t have a microprocessor around to clean up the mess.

“Self-Destruct” in Avionics: What It Usually Means (and What It Doesn’t)

The phrase “self-destruct” makes people think of movie countdowns and dramatic sparks. In reality, protective behaviors in military electronics often have

a more specific goal: deny sensitive information to unauthorized hands.

Anti-tamper: protecting secrets, not creating fireworks

Military systems may incorporate anti-tamper features to reduce the chance that someone can capture and reverse-engineer critical technology.

Depending on the system, that might include coatings, sensors, secure enclosures, or mechanisms that erase or disable sensitive parts if tampering

is detected.

In practice, “self-destruct” can mean “the device becomes useless for intelligence value,” not “it explodes.” Sometimes it’s key material being wiped. Sometimes

it’s deliberate damage to critical components. The details vary widely and are not the kind of thing reputable organizations publish as a DIY guide (for obvious

reasons).

Why would an attitude gyro need protection?

Not every attitude indicator has sensitive tech worth guardingbut some military-grade avionics components do. Even older units can contain specialized mechanical

designs, materials, or integration approaches that were expensive to develop and valuable to keep out of an adversary’s toolkit.

Also, the idea of “self-protection” can apply to more than secrecy. Some devices are designed to fail in a controlled way, or to prevent unsafe reuse after damage.

That’s not the same as self-destruct, but it can look similar from the outside: a part that refuses to cooperate after a certain condition is met.

From Spinning Metal to Beams of Light: The Evolution of Gyros

Mechanical gyros: reliable, elegant, and eventually worn out

Mechanical gyros were foundational in aviation and spaceflight. They’re intuitive (in a physics-professor way) and can be incredibly precise for short time scales.

But they have moving parts, and moving parts wear. Bearings age, friction changes, and maintenance becomes a lifestyle.

Still, the concept remains the same: create a stable reference so the vehicle can understand its attitude and motion even when visual cues disappear. In instrument

conditions, that stable reference can be the difference between “controlled flight” and “why is the horizon doing interpretive dance?”

Laser ring gyros and fiber-optic gyros: the no-moving-parts era

Modern inertial systems often use laser ring gyros or fiber-optic gyros. Instead of a spinning wheel, they measure rotation by comparing light traveling in opposite

directions. No rotor. No bearings. Much less mechanical wear.

For pilots, the user experience is “it just works.” For engineers, it’s “we replaced a complicated mechanical miracle with a complicated optical miracle.”

Progress is beautiful like that.

Why This Matters Beyond Cool Teardown Videos

Because humans get confused in 3D faster than they admit

Spatial disorientation is a real aviation hazard. Our bodies are great at walking around and terrible at reliably sensing attitude in clouds, at night, or during

sustained acceleration. Instruments exist because biology has limits.

An attitude indicator gives an immediate pitch-and-bank reference. But the pilot’s job isn’t to worship one instrument; it’s to interpret a system. Cross-checking

and understanding failure modes is what turns “data” into “safe decisions.”

Because redundancy is a philosophy, not a shopping list

Aviation doesn’t aim for “nothing ever fails.” It aims for “when something fails, you still have a safe path forward.” The attitude reference system is a great example:

mechanical gyros, vacuum systems, electric backups, AHRS, standby instrumentsdifferent eras solved the same problem with layered approaches.

Practical Takeaways: The “So What?” List

- The gyro stays upright because angular momentum resists changes in orientation, and gimbals let the aircraft move around it.

- Gyros drift due to precession, friction, and design tradeoffsso cross-checking matters.

- Self-erection helps keep the instrument usable, but it can introduce slow errors in unusual attitudes or long turns.

- “Self-destruct” usually means protection: disabling or erasing sensitive elements, not Hollywood explosions.

- Modern systems use light (laser/fiber gyros) and solid-state sensors for more robustness and less wear.

Conclusion

A fighter jet gyro “staying upright” is one of those moments where physics looks like a magic trickuntil you realize it’s an honest, disciplined trick,

performed by a spinning rotor and a set of gimbals that refuse to panic.

And the idea of that same instrument “self-destructing” isn’t about drama; it’s about design priorities. Military hardware often assumes it may end up in

the wrong hands, and it plans accordingly. Put those together and you get something wonderfully paradoxical: a device built to be stable, precise, and calm…

that may also be built to never tell its secrets.

Experiences Related to “A Gyro Staying Upright” (Extra 500+ Words)

Even if you’ve never touched a real attitude indicator, you’ve probably had the “whoa” moment in a simulator or a video where the gyro assembly is exposed.

The first experience many students describe (especially in instrument training) is emotional, not technical: relief. Clouds outside, no horizon, the airplane

feels like it’s doing something mysteriousand then the attitude indicator sits there like a calm friend saying, “Here’s what’s actually happening.”

That calmness can be addictive. The instrument is so immediate that people start trusting it the way they trust gravity. But experienced instructors tend to

emphasize a second experience: humility. When you learn about drift and precession, it changes your relationship with the instrument. You stop thinking of it

as a “truth screen” and start thinking of it as a “best-current-answer device” that lives in a real machine with real imperfections.

Another common experience shows up when pilots practice unusual attitude recoveries in training devices. The lesson is not “look at one thing.” It’s “build a

mental model.” If you’re nose-high and slow, your airspeed and vertical speed will tell a story that matches (or contradicts) what the attitude indicator shows.

When the readings align, your confidence rises. When they don’t, you learn to diagnose: is this a sensor issue, a setup issue, or a pilot interpretation issue?

That is a very “pilot brain” momentless about flying the airplane and more about managing information under stress.

Maintenance and museum restoration communities have their own version of the experience. People who refurbish vintage instruments often describe the “spin-up”

like a tiny ceremony. You power the unit, hear the rotor come alive, and suddenly the whole mechanism feels less like a part and more like a living system.

Then you tap the case lightly or tilt it and watch the horizon behave exactly as the textbooks promised. It’s deeply satisfying because it’s tactile truth:

not software, not a screen, but a physical system demonstrating a physical law.

If you’ve ever watched a teardown video of a fighter-grade unit, there’s also the experience of respect bordering on disbelief. You see intricate gears,

precision bearings, and linkages that look like they belong in a luxury watchexcept they were built to survive vibration, temperature extremes, and years of

operational abuse. That contrast tends to stick with people: delicate-looking parts doing rugged jobs.

Finally, there’s the experience of realizing how design choices reflect real-world assumptions. For example, a self-erecting mechanism feels like a gift

until you imagine a scenario where you hold an unusual attitude for longer than the design expects. Suddenly, “helpful correction” becomes “subtle misinformation.”

That’s not a flaw so much as a reminder: every engineering solution carries a worldview about normal conditions, normal behavior, and normal use.

Put all those experiences together and you get why this topic fascinates people far beyond aviation nerd circles. The gyro staying upright is a simple visual

metaphor for something bigger: stability is engineered. It’s maintained, corrected, and cross-checked. And sometimes, to protect what matters, the same system

that stays calm under pressure is designed to refuse cooperation when the world gets… less friendly.