Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Headcanon” Means (and Why Voldemort Collects It Like Horcruxes)

- Canon Building Blocks We’re Using (So We Don’t Accidentally Invent a Different Franchise)

- 15 Voldemort Headcanons That Are Wild Enough To Be True

- 1) He didn’t choose “Voldemort” to sound coolhe chose it to erase “Tom.”

- 2) He obsessed over Hogwarts because it was the first place that “picked” him.

- 3) The “pure-blood” ideology was propaganda he didn’t fully believebut it was useful.

- 4) He was a “collector” long before Horcruxeshe hoarded proof that he mattered.

- 5) He studied Muggle systems in secretnot out of respect, but for strategy.

- 6) He didn’t just fear deathhe feared being forgotten.

- 7) He had one irrational superstition: numbers matter because stories matter.

- 8) He practiced “being charming” like it was spellwork.

- 9) He kept Nagini close because she was the only “relationship” he could control completely.

- 10) He hated laughter because it reminded him that people can be free.

- 11) He avoided mirrorsnot because of vanity, but because he couldn’t stand evidence of change.

- 12) He secretly respected Dumbledore the way a storm “respects” a mountain.

- 13) He built his defenses to punish curiositybecause curiosity is what created him.

- 14) The Taboo on his name was less about tracking and more about branding fear.

- 15) He overexplains at the end because he thinks reality should obey narrative.

- How to Use These Headcanons in Fanfic (Without Breaking Canon)

- Conclusion: Why “Wild but True” Voldemort Theories Hit So Hard

- of Potterhead Experience: Watching Voldemort Headcanons Evolve

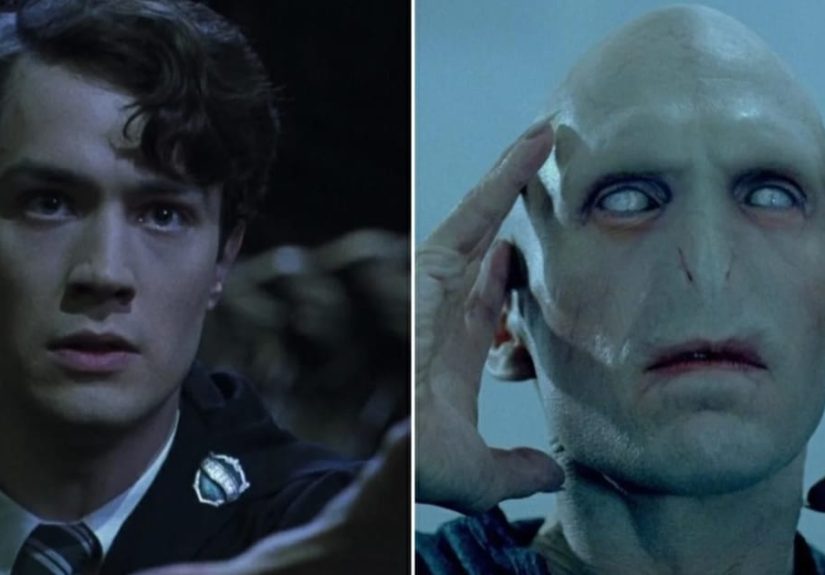

Voldemort is the kind of villain who walks into a scene and instantly lowers the room temperature by twelve degreesyet fandom can’t stop

handing him a clipboard labeled “Explain Yourself.” And honestly? Fair. Tom Riddle’s canon story is packed with gaps, vibes, and “wait, so

you did what at age sixteen?” energy. That’s prime headcanon real estate.

This list is for the Potterheads who love theories that feel like they could’ve been one extra chapter in Half-Blood Princethe ones that are

a little unhinged, but still snap neatly onto canon like LEGO. We’re not rewriting Voldemort into a misunderstood cinnamon roll. We’re just asking:

what if the scariest wizard of the century also had a few painfully human habits… and one or two terrifyingly logical reasons for being Like That?

What “Headcanon” Means (and Why Voldemort Collects It Like Horcruxes)

A headcanon is a fan-belief that isn’t officially stated but feels consistent with the story’s logic. The best headcanons don’t fight canon; they

interpret it. Voldemort attracts them because his canon is both detailed (we get key memories, motives, and milestones) and strategically incomplete

(we don’t get every private thought, routine, or long-term plan). Add in his obsession with immortality, symbolism, and control, and you’ve got a

character who practically begs readers to connect dots.

Canon Building Blocks We’re Using (So We Don’t Accidentally Invent a Different Franchise)

- He was born Tom Marvolo Riddle and reinvented himself through names and fear.

- He’s tied to Slytherin lineage and Parseltongue, and he exploits that legacy.

- He pursued immortality through Horcruxes and aimed for a symbolic “seven.”

- He built a movement (Death Eaters) using ideology, intimidation, and selective reward.

- He’s terrified of deathso much that Rowling says it’s his core fear.

- His magic is strategic: protections, contingencies, and layered defenses are his love language (the bad kind).

15 Voldemort Headcanons That Are Wild Enough To Be True

1) He didn’t choose “Voldemort” to sound coolhe chose it to erase “Tom.”

The anagram flex is iconic, but the motive is darker: “Tom” is ordinary, boyish, and painfully Muggle-coded. If you’re a kid who grew up feeling

powerless, unwanted, and anonymous, “Tom” isn’t a nameit’s a sentence. Headcanon: he loved the effect of “Lord Voldemort,” but the real prize was

deleting the part of himself that could be dismissed as common.

Why it fits: canon repeatedly frames him as someone who rejects his origins except when they give him leverage. A new name isn’t branding; it’s

self-surgery.

2) He obsessed over Hogwarts because it was the first place that “picked” him.

Headcanon: Voldemort’s attachment to Hogwarts isn’t nostalgiait’s ownership. Hogwarts is where he was admired, where adults validated him, where rules

bent around his brilliance. For a kid who had no stable home, Hogwarts wasn’t just school; it was proof that the world had a slot with his name on it.

That makes his later fixation on the school (and on founder relics) feel less random. He isn’t only collecting powerful objectshe’s collecting

belonging and turning it into a weapon.

3) The “pure-blood” ideology was propaganda he didn’t fully believebut it was useful.

Voldemort is famously a half-blood who leads a purity-obsessed movement. That contradiction works perfectly for a leader who sees ideology as a tool,

not a truth. Headcanon: he didn’t wake up thinking “pure-bloods are superior.” He woke up thinking, “people want someone to blame, and I can sell them a

story that makes me the answer.”

This is also why he keeps inner circles competitive: if followers are busy proving themselves, they don’t have time to question the leader’s logic.

4) He was a “collector” long before Horcruxeshe hoarded proof that he mattered.

Before he split his soul, he likely collected smaller things: records of awards, trophies, letters, stolen keepsakesanything that said, “I was here.”

Headcanon: Horcruxes weren’t his first attempt at permanence. They were his most extreme escalation.

It’s a frighteningly plausible character path: start by hoarding validation; end by hoarding immortality.

5) He studied Muggle systems in secretnot out of respect, but for strategy.

The irony: the wizard who despises Muggles may be one of the most diligent students of Muggle power structures. Headcanon: teenage Tom Riddle devoured

Muggle history and politics because it taught him how ordinary people can be manipulated at scale. Not because he wanted to join thembecause he wanted

to outgrow everyone.

It explains why his movement feels like more than random cruelty. It’s organized, symbolic, and psychologically targeted.

6) He didn’t just fear deathhe feared being forgotten.

Canon tells us he fears death. Headcanon takes it one step further: what he truly can’t tolerate is the idea that the world continues without him, barely

noticing. Death is humiliating because it’s ordinary. And nothing insults Voldemort like the concept of being ordinary.

That’s why the “Dark Lord” persona is so theatrical. It’s immortality plus applause.

7) He had one irrational superstition: numbers matter because stories matter.

Voldemort’s fixation on “seven” reads like a villain doing numerology with a wand. Headcanon: he believed in magical symbolism the way some people believe

in fatebecause symbolism makes chaos feel controllable. Seven isn’t just “powerful,” it’s “complete.” If he could build a perfect set, he could build a

perfect self.

8) He practiced “being charming” like it was spellwork.

Tom Riddle could be charismatic. Headcanon: he treated charm like a techniqueobserving, mirroring, rewarding, withdrawing. Not because he wanted

connection, but because he wanted predictable outcomes.

This makes his later coldness more terrifying, not less. He can perform warmth without ever feeling it, which is honestly the scariest party trick.

9) He kept Nagini close because she was the only “relationship” he could control completely.

Snakes don’t challenge your worldview. They don’t ask for empathy. They don’t call you “Tom.” Headcanon: Nagini wasn’t just a weapon or containershe

was companionship with the friction sanded off.

Parseltongue also creates privacy: a secret language in a world of eavesdropping and betrayal. For a paranoid ruler, that’s comfort.

10) He hated laughter because it reminded him that people can be free.

Voldemort’s world is built on fear and hierarchy. Laughter collapses hierarchy. It turns the mighty into the ridiculous. Headcanon: he wasn’t just angry

when people mocked himhe was destabilized. Humor is social magic that he can’t fully command.

(Yes, this also means the Weasley twins were basically his natural predator.)

11) He avoided mirrorsnot because of vanity, but because he couldn’t stand evidence of change.

Headcanon: Voldemort’s horror at aging wasn’t about wrinkles; it was about losing control. He chased immortality partly because the body is a betrayal:

it changes without permission. Avoiding mirrors becomes a small, daily denial ritualif he doesn’t look, he doesn’t have to admit the clock exists.

12) He secretly respected Dumbledore the way a storm “respects” a mountain.

Voldemort doesn’t do admiration, but he does acknowledge obstacles. Headcanon: his obsession with defeating Dumbledore wasn’t only practical; it was

existential. As long as Dumbledore stood, Voldemort wasn’t the undisputed apex of the wizarding world.

That’s why he never seems fully satisfied. There’s always one more proof of supremacy to acquire.

13) He built his defenses to punish curiositybecause curiosity is what created him.

Look at the layered protections around the Horcruxes: they’re not just security; they’re a moral test with teeth. Headcanon: he designed defenses that

specifically punish the traits he once hadcuriosity, boldness, the desire to know forbidden things.

It’s projection as architecture: “If you want to find what I found, you should suffer like I suffered.”

14) The Taboo on his name was less about tracking and more about branding fear.

The tracking angle is efficient, sure. But headcanon: the real victory is psychological. When people can’t say your name, you become a conceptan

atmospherean unavoidable shadow. He doesn’t just want to be feared; he wants fear to become the default setting of the world.

15) He overexplains at the end because he thinks reality should obey narrative.

Voldemort loves grand reveals, prophecy, symbolism, “chosen” logic. Headcanon: he genuinely believes the universe has rules like a legend doesif he has

the Elder Wand, if he has the right blood, if he checks the right boxes, then the ending is guaranteed.

That’s why his defeat is so fitting: he’s not beaten by “more power.” He’s beaten by misunderstanding the kind of magic that mattersloyalty,

sacrifice, and choices that don’t look impressive on a résumé.

How to Use These Headcanons in Fanfic (Without Breaking Canon)

- Anchor each theory to a moment. A single scene can support a whole interpretation if you write it carefully.

- Keep him strategic. Even emotional headcanons should come out as control attempts, not open vulnerability.

- Let consequences stay real. A “human” Voldemort is still Voldemort: harm, cruelty, manipulation, and fear remain the footprint.

- Use contrast. Put his private rituals next to his public terror. That tension is where the chills live.

Conclusion: Why “Wild but True” Voldemort Theories Hit So Hard

Voldemort works as a villain because he’s both mythic and recognizable: the kid who learned early that control feels safer than love, then never stopped

leveling up. The most satisfying headcanons don’t soften himthey sharpen him. They show how a person can turn pain into power, power into ideology, and

ideology into a machine that eats everyone else.

And if some of these theories made you whisper, “Wait… that actually makes sense,” congratulations. You’ve just created a Horcrux. For your brain.

Please store it responsibly.

of Potterhead Experience: Watching Voldemort Headcanons Evolve

If you’ve spent any time in Harry Potter fandom spacesforums, Tumblr threads, TikTok breakdowns, Discord servers, or the timeless tradition of arguing in

a comment section at 2 a.m.you’ve probably noticed something: Voldemort headcanons tend to swing between two extremes. On one end, he’s treated like a

horror-movie monster, pure evil in designer robes. On the other end, people try to “explain” him so hard that he starts to sound like a sad Victorian

orphan who just needed a hug and a hot cocoa. The most interesting fandom experience is what happens in the middle, where readers collectively test

theories against canon like they’re stress-testing a bridge.

A common pattern is the “memory rewatch.” Someone rereads the Pensieve chapters and suddenly the fandom has a new fixation: the way Tom Riddle performs

politeness, the way adults respond to him, the way he seems to treat people as mechanisms rather than humans. Then the headcanons bloom: maybe he practiced

charm as a tool; maybe he collected praise like currency; maybe he learned early that fear gets faster results than friendship. None of that contradicts

canonit’s the fandom doing what it does best: filling emotional and behavioral gaps with interpretations that feel earned.

Another shared experience is “movie-vs-book drift.” In film, Voldemort can feel like an always-on supervillain with dramatic entrances. In the books,

his obsession with symbolism, artifacts, and legacy is more visible, which makes headcanons about his psychology and planning feel more plausible. Fans

often swap notes: “This scene plays one way on screen, but the book implies something colder.” That’s where theories like “he feared being forgotten” or

“he used ideology as propaganda” tend to flourishbecause book-Voldemort reads like someone building a system, not just throwing curses.

And then there’s the delightfully communal sport of “headcanon realism”: fans trying to imagine mundane details that still feel frightening. What does he

do when he’s alone? Does he sleep? Does he rehearse speeches? Does he avoid mirrors? Those questions sound silly until you realize they’re really asking,

“How does someone live inside that much fear?” The fandom’s best answers usually aren’t cute; they’re chillingly practicalprivate rituals of control,

routines that reduce uncertainty, and habits that keep “Tom” buried under “Voldemort.”

The weird magic of these shared experiences is that they make the story feel bigger without changing its spine. You come for the wild theories, stay for

the moment a headcanon clicks into place and makes an old scene feel new. It’s not about redeeming Voldemort. It’s about understanding how a character

can be both unbelievable and, in the scariest ways, painfully believable.