Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Inflation 101: The Return You See vs. the Return You Keep

- The Three Main Ways Inflation Changes Market Returns

- How Inflation Affects Returns by Asset Class

- Stocks: Not an automatic inflation shield (but not helpless, either)

- Margin squeeze vs. pricing power

- Growth vs. value: why timing matters

- Bonds: Inflation is the arch-nemesis of fixed payments

- The inverse relationship: bond prices and yields

- Inflation risk premium

- Cash and cash-like investments: safe in value, risky in purchasing power

- Inflation-protected bonds: TIPS (and why the “P” is doing a lot of work)

- Real assets: real estate, commodities, and gold

- Expected vs. Unexpected Inflation: The Surprise Is the Problem

- Historical Snapshots: Inflation’s Greatest Hits (and Misses)

- So… What Can Investors Do About It?

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Real-World “Inflation Moments”: Experiences Investors Commonly Run Into (500+ Words)

Inflation is the sneaky roommate of investing: it doesn’t steal your money outright, it just slowly eats your snacks and then acts surprised when the pantry is empty. In markets, inflation changes what returns meanand sometimes what investors are willing to pay for those returns.

This guide breaks down how inflation affects market returns across stocks, bonds, cash, and “real assets,” why surprises matter more than headlines, and how investors often think about inflation risk without moving into a bunker made of canned beans. (No judgment if you do. Beans have excellent shelf life.)

Quick note: This is educational, not personalized investment advice. Inflation is complicated, and your goals/time horizon matter.

Inflation 101: The Return You See vs. the Return You Keep

Nominal returns vs. real returns (the “after-inflation” truth)

Market returns are usually quoted in nominal termswhat your account balance did in dollars. But what investors actually care about is real return: the growth in purchasing power after inflation.

Here’s the simple math:

Real return ≈ Nominal return − Inflation rate

So if your portfolio gained 8% and inflation ran 4%, your real return was roughly 4%. You’re still aheadbut not as far ahead as your statement wants you to believe.

Over long stretches, this difference is massive. A market that averages around 10% nominal doesn’t feel the same if inflation averages 3% versus 6%. Same nominal “movie,” totally different ending.

How inflation is measured (and why the measure matters)

In the U.S., inflation is commonly discussed using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which tracks changes in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of goods and services. The Federal Reserve, however, often emphasizes inflation measured by the PCE price index when discussing its longer-run goal.

Translation: you’ll hear different inflation numbers depending on the scoreboard being used. That doesn’t mean anyone is “making it up.” It means the basket, weights, and methodology differlike measuring your height with shoes on vs. off. The direction is what matters most; the exact number depends on the yardstick.

The Three Main Ways Inflation Changes Market Returns

1) Inflation changes what future money is worth

Stocks and bonds are basically promises about future cash flowsdividends, interest payments, or business earnings that (hopefully) show up later. Inflation reduces the future purchasing power of those dollars. If investors think inflation will be higher, they generally demand a higher return to compensate. That one adjustment can ripple through all asset prices.

2) Inflation influences interest rates (and the discount rate)

When inflation rises, central banks may raise policy rates to cool demand. Even when the Fed doesn’t move immediately, bond markets often adjust yields as inflation expectations shift.

Why does this matter for returns?

- Bonds: Higher yields usually mean lower existing bond prices (more on that soon).

- Stocks: Higher rates can raise the “discount rate” used to value future corporate cash flows, which can put pressure on valuationsespecially for companies whose profits are expected far in the future.

Think of it like this: when the “price of money” goes up (higher rates), investors become pickier about what they’re willing to pay for future earnings.

3) Inflation can change investor psychology and valuations

Inflation doesn’t just affect spreadsheetsit affects behavior. When inflation is high or unpredictable, investors may worry about policy tightening, slower growth, and profit margins. That can reduce the price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple people are willing to pay.

In plain English: companies might still grow sales in nominal dollars, but stocks can struggle if investors decide those earnings aren’t worth as much as they used to be.

How Inflation Affects Returns by Asset Class

Stocks: Not an automatic inflation shield (but not helpless, either)

Stocks are often described as “good long-term inflation hedges,” and there’s truth thereover long periods, corporate revenues and earnings can rise with prices. But in the short to medium term, inflation can still hit stocks through several channels:

Margin squeeze vs. pricing power

Inflation raises input costswages, materials, shipping, energy. If a company can raise its prices without losing customers, it has pricing power and may hold margins steady. If it can’t, profits get squeezed.

This is why inflation often creates a “winners and losers” market rather than lifting all boats. Some businesses pass costs through easily (certain consumer staples, healthcare niches, essential services). Others get pinched (companies in hyper-competitive industries, or those reliant on discretionary spending when household budgets tighten).

Growth vs. value: why timing matters

When rates rise alongside inflation, “long-duration” stocksoften high-growth companies whose profits are expected far in the futurecan be more sensitive to valuation pressure. Meanwhile, companies with nearer-term cash flows, dividends, or lower valuations can sometimes look more attractive in relative terms.

Important caveat: sectors and styles don’t follow rules like a polite spreadsheet. They behave more like a cat: sometimes predictable, often not, and always convinced it’s in charge.

Bonds: Inflation is the arch-nemesis of fixed payments

Bonds pay a fixed stream of interest (unless inflation-adjusted). That makes inflation a direct threat to real returns.

The inverse relationship: bond prices and yields

A core principle: when market interest rates (yields) go up, existing bond prices typically fall. Why? New bonds come out paying higher yields, so older bonds must get cheaper to compete.

This is why periods of rising inflation (and rising rate expectations) can produce painful bond market drawdownsespecially for longer-maturity bonds. Longer maturities generally mean greater sensitivity to rate moves (often described as higher “duration”).

Inflation risk premium

Bond investors may demand extra yield when inflation is uncertain. That extra yield can weigh on bond prices today. Even if inflation later cools, the path matters: returns depend on when yields moved and how quickly the market repriced.

Cash and cash-like investments: safe in value, risky in purchasing power

Cash feels stable because it doesn’t fluctuate much day to day. But inflation can quietly deliver negative real returns. If a savings account yields 2% while inflation is 4%, the real return is roughly -2%.

Cash can still be usefulfor emergencies, upcoming expenses, and flexibility. Just don’t confuse “not volatile” with “risk-free.” Inflation is a risk. It’s just wearing slippers.

Inflation-protected bonds: TIPS (and why the “P” is doing a lot of work)

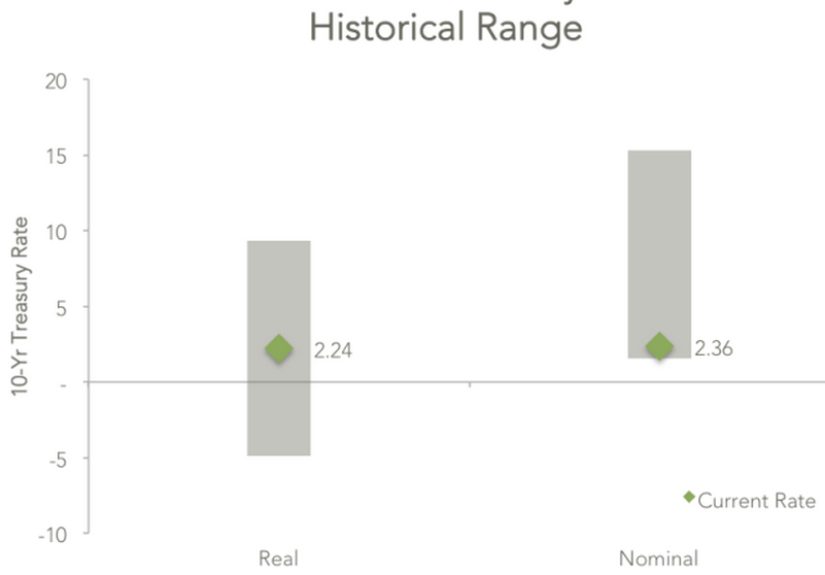

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) are U.S. Treasuries designed to protect against inflation. Their principal adjusts with inflation, and interest payments are based on that adjusted principal. At maturity, investors receive the inflation-adjusted principal or the original principal (whichever is greater), which helps protect purchasing power.

TIPS aren’t magic. Their market prices can still move with real yields, and their “protection” is tied to the inflation index used. But they’re one of the cleanest tools for addressing inflation risk in a bond portfolio.

Real assets: real estate, commodities, and gold

“Real assets” are often discussed as inflation hedges because they’re linked to physical goods or real-world cash flows.

- Real estate: Rents and property values can rise with inflation over time, but higher interest rates can also make financing more expensive and pressure valuations.

- Commodities: They can respond quickly to inflation shocks, especially when inflation is driven by supply constraints (energy spikes, for example). But commodities can be volatile and cyclical.

- Gold: Often treated as an “alternative store of value.” It may shine in certain inflation or uncertainty regimes, but it doesn’t produce cash flow, so outcomes depend heavily on investor sentiment and real rates.

The key takeaway: real assets can help diversify inflation risk, but they come with their own kinds of risk. “Inflation hedge” does not mean “guaranteed good time.”

Expected vs. Unexpected Inflation: The Surprise Is the Problem

Markets are forward-looking. If inflation is widely expected, prices may already reflect it. The bigger impact tends to come from unexpected inflationwhen inflation prints above (or below) what investors anticipated.

Surprises can shift expectations for central bank policy. If investors think the Fed will respond with tighter policy, discount rates can rise, bond yields can jump, and both stocks and bonds can reprice quickly.

This is why two identical inflation rates can produce very different market reactions depending on what the market expected the number to be.

Historical Snapshots: Inflation’s Greatest Hits (and Misses)

The 1970s: when “real returns” got real sad

The 1970s are the classic U.S. case study because inflation was high and persistent, and markets dealt with a difficult mix of slow growth and price pressures (often described as stagflation). Equity markets were volatile, and real returns for many assets struggled. Bonds had a rough time as yields rose dramatically over the decade into the early 1980s.

One of the underrated lessons from this era is that nominal earnings can rise while valuations fall. Investors may simply refuse to pay high multiples when inflation and policy uncertainty feel unanchored. That valuation “compression” can overwhelm nominal growth.

From the mid-1980s to the 2010s: the tailwind of falling inflation

When inflation trends lower and stays more stable, markets often benefit from lower interest rates and steadier expectations. Bonds can do well when yields trend down, and stocks can benefit from higher valuation multiples because future cash flows are discounted at lower rates.

In a world of lower inflation, the market may spend more time arguing about innovation, productivity, and “soft landing” vibesrather than whether your groceries are speed-running a price level expansion pack.

The early 2020s: inflation spikes and fast repricing

When inflation rises quickly, markets can reprice fast. One common pattern is simultaneous stress in both stocks and bonds if yields jumpbecause bonds lose price value as yields rise, while stocks can face valuation pressure through higher discount rates.

This is why some investors learned a hard lesson: diversification works over time, but it can feel less comforting in the exact moment everyone is panicking together.

So… What Can Investors Do About It?

1) Track real returns, not just nominal headlines

If you only look at nominal returns, you may feel rich while quietly getting poorer in purchasing power. Real return thinking doesn’t have to be complicatedjust keep inflation in the conversation.

2) Diversify across inflation sensitivities

Different assets react differently to inflation regimes. A portfolio that mixes equities, a thoughtful bond allocation (including attention to maturity/duration), and perhaps some inflation-aware diversifiers can reduce the chance that one surprise dominates your outcome.

3) Don’t ignore bond structure (maturity matters)

With bonds, the details matter: maturity, duration, credit quality, and whether the bond is inflation-linked. If inflation pushes rates up, longer maturities tend to be more price-sensitive. That doesn’t mean “never own long bonds,” but it does mean you should understand what you’re holding and why.

4) Favor businesses with pricing power and resilient demand

Within stocks, companies that can maintain marginsby passing costs through, controlling expenses, or operating in essential categoriesmay hold up better when inflation is sticky.

5) Rebalance (the unglamorous hero)

Inflationary periods often create big relative moves: some assets drop, some spike, some just sit there smugly. Rebalancingperiodically returning your portfolio to its target mixcan force “buy low, sell high” behavior without you having to predict the future like a caffeinated oracle.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does inflation always hurt stocks?

No. Stocks can do fine under moderate inflation, especially if growth is healthy and inflation is expected. Stocks tend to struggle more when inflation is high, volatile, or triggers aggressive policy tighteningor when inflation squeezes corporate margins.

Why can bonds have negative returns in inflationary periods?

Because rising inflation often pushes yields higher, and bond prices generally fall when yields rise. If yields move quickly, price declines can outweigh the interest you receive in the short term.

Are TIPS guaranteed to outperform regular Treasuries?

No. TIPS are designed to protect against inflation, but outcomes depend on inflation relative to what the market already priced in, plus movements in real yields. They can be very usefuljust not automatically “better” in every environment.

Real-World “Inflation Moments”: Experiences Investors Commonly Run Into (500+ Words)

Inflation sounds academic until it shows up in your everyday decisionsthen it becomes painfully personal. While every investor’s story is unique, there are a few “inflation moments” that come up again and again, and they’re worth learning from because they reveal how inflation affects market returns in practice (not just on paper).

The “My raises feel smaller than my bills” moment

A lot of people first notice inflation when their paycheck goes up but their lifestyle doesn’t. That’s the purchasing-power lesson in real time. In investing terms, it’s the same shock: a portfolio can grow in nominal dollars while you feel like you’re running in place. This is often when investors start asking better questionslike “What’s my return after inflation?” and “Am I taking enough risk to outpace rising prices over the long run?” The experience tends to push people away from focusing only on account balances and toward thinking about what those balances can actually buy.

The bond surprise: “Wait, aren’t bonds supposed to be the calm part?”

Many conservative investors (and plenty of aggressive ones, too) are surprised the first time they see bond funds drop meaningfully. The mental model is: bonds pay interest, therefore bonds are safe, therefore the line should go up politely. But when inflation rises and yields jump, existing bonds can fall in price. That can feel like betrayalespecially for investors who bought bonds expecting stability. The more experienced takeaway usually becomes: bonds aren’t “risk-free,” they’re “risk-different.” They can still be stabilizing over time, but the path matters, and interest-rate risk is real.

The “everything is expensive, but my ‘inflation hedge’ is down” moment

Some investors buy an inflation hedge expecting instant reliefthen get frustrated when it doesn’t behave like a superhero. Real estate can wobble if mortgage rates rise. Commodities can whipsaw. Gold can stall if real interest rates rise. Even stocks can struggle if higher inflation leads to tighter policy and lower valuation multiples. This experience often teaches a more mature lesson: hedges are about probabilities and diversification, not guarantees. A hedge can reduce risk across scenarios, but it won’t always pay off at the exact moment you feel inflation most.

The “pricing power is real” moment

Inflation also makes business quality easier to see. Investors start noticing which companies can raise prices without losing customersand which ones can’t. In everyday terms: some brands keep selling even after a price hike, and others get ghosted the moment a competitor offers a coupon. In market terms, pricing power can help protect margins and support returns when costs rise. Many investors who live through inflationary periods come out more focused on fundamentalscash flow, balance sheet strength, and the ability to adaptbecause those traits often matter more when money isn’t cheap.

The calm-on-purpose response: “I’m not going to outguess CPI prints”

Finally, a lot of investors end up with a surprisingly boring (and effective) response: they stop trying to trade inflation headlines. Instead, they diversify, keep an eye on real returns, and rebalance. They accept that inflation data can move markets in the short run, but long-run outcomes are driven by discipline. It’s not flashy, but neither is flossingand flossing still wins.