Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The stories I used to believe (and occasionally repost)

- Then my brain filed a surprise HR complaint

- Stigma isn’t just meanit’s a barrier with real consequences

- Self-stigma: when you become your own comment section

- What mental illness actually looks like (spoiler: mostly like people)

- Work, school, and the art of not oversharing

- Treatment: the boring, beautiful stuff that works

- How to talk to someone without accidentally being a human grenade

- So… what changed?

- 500 more words: the after-party of becoming “one of them”

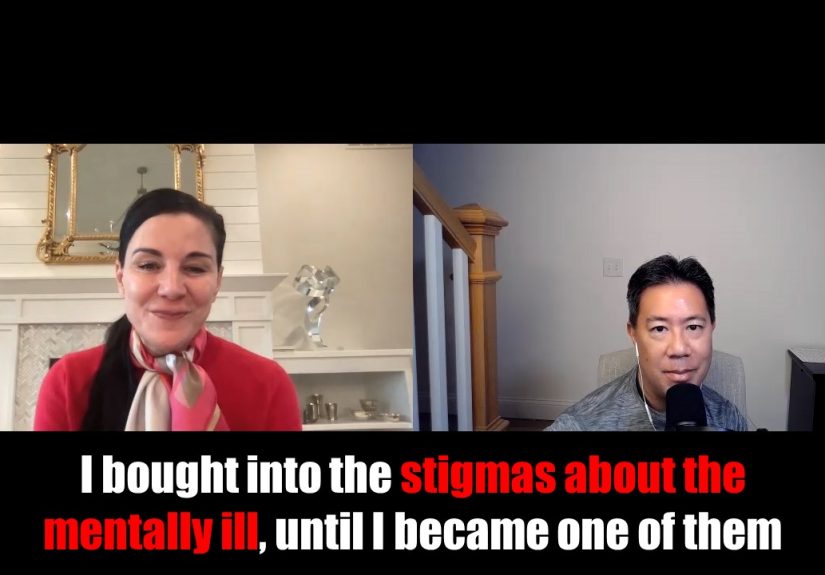

I used to think I was an open-minded person. I recycled. I tipped well. I “checked in” on friends with a heart emoji

that looked vaguely medical. And when it came to mental illness, I was absolutely sure I understood it.

Sure, I didn’t say the quiet part out loud, but my brain had a whole filing cabinet labeled “People Like That.”

The mentally ill were either scary, fragile, unpredictable, attention-seeking, or all of the abovedepending on what

movie I’d seen most recently. If someone mentioned therapy, I’d nod like a supportive houseplant while secretly

thinking, Couldn’t you just… be tougher?

Then one day my own brain decided to audition for a disaster movie without telling me. Plot twist: I got the role.

And the stigmas I’d carried around like harmless little opinions? They turned out to be heavy, sharp, and extremely

interested in my personal life.

This isn’t a clinical guide. It’s a confession with receiptsbased on public health data, medical guidance, and

research from major U.S. institutionsplus the humbling experience of realizing “them” is not a different species.

It’s just… people. It’s me. Possibly your barista. Definitely your group chat.

The stories I used to believe (and occasionally repost)

Stigma about mental illness is sneaky. It rarely shows up wearing a villain cape. It shows up as “common sense,”

“a joke,” or “I’m just being honest.” Mine sounded like this:

Myth #1: Mental illness is a personality flaw with a fun label

If someone struggled, I assumed they were weak, dramatic, or “not trying hard enough.” I treated depression like a

motivation problem, anxiety like a bad habit, and trauma like an inconvenient backstory. I didn’t think I was being

cruel. I thought I was being practicallike a life coach with zero qualifications (the worst kind).

Myth #2: Mentally ill people look a certain way

I pictured extremes: someone muttering on a sidewalk, someone in a movie hospital gown, someone snapping violently

in a courtroom drama. In my head, mental illness was always visible, always obvious, always “other.”

Myth #3: Treatment is for people who can’t handle reality

Therapy sounded indulgent. Medication sounded like surrender. I respected “pushing through” more than “getting help.”

I thought resilience was gritting your teeth until your molars filed for workers’ comp.

And here’s the nasty part: those myths didn’t just shape how I saw others. They trained me for how I’d treat myself

the moment I needed help.

Then my brain filed a surprise HR complaint

It started small. Sleep got weird. My thoughts developed a hobby: sprinting. I felt tired and wired at the same time,

like someone poured espresso into my bloodstream and then replaced my bones with wet sand.

I didn’t call it anxiety at first. I called it “being busy.” I didn’t call it depression when the fog rolled in. I called

it “a slump.” I used euphemisms the way people use throw pillowsto make the room look normal.

Eventually, my body stopped cooperating with my denial. My heart raced at nothing. My stomach dropped like I was

perpetually on a roller coaster designed by my worst enemy. Concentration evaporated. I’d reread the same email

fourteen times and still miss the part where I was the problem.

Here’s what shocked me: none of this felt like “going crazy.” It felt like being intensely human, except the volume

knob was broken. And when I finally looked up the numbers, I realized how common this actually is. In the U.S., more

than one in five adults live with a mental illness in a given year. That’s not a weird corner of societythat’s a packed

airplane cabin.

Stigma isn’t just meanit’s a barrier with real consequences

If stigma were only about rude comments, we could solve it with manners and a strongly worded poster. But mental health

stigma is structural. It affects whether people seek care, how they’re treated at work, how health systems respond, and

even whether they end up in places that were never meant to be treatment centers.

Stigma delays help-seeking

Research consistently shows stigma has a measurable negative effect on whether people seek professional help. That’s the

part I lived: I didn’t just feel bad; I felt ashamed for feeling bad. I waited. I minimized. I told myself I didn’t “deserve”

help because someone else “had it worse.” (My brain’s favorite game: Competitive Suffering.)

Stigma turns workplaces into performance theaters

Even when someone is doing their job well, they may fear that disclosing a mental health condition will lead to being

seen as unreliable or “a risk.” So people mask. They burn out quietly. They take sick days for “migraines” when the truth

is panic. They avoid accommodations they’re legally allowed to request because they don’t want to be labeled.

Stigma helps funnel people into the criminal justice system

This part is hard to sit with: when mental health care is inaccessible, underfunded, or avoided due to shame, crises don’t

disappear. They escalate. In the U.S., a substantial share of incarcerated people report histories of mental health problems.

Jails and prisons end up acting like de facto psychiatric facilitiesexcept they weren’t designed, staffed, or funded for healing.

Stigma doesn’t just hurt feelings. It changes outcomes.

Self-stigma: when you become your own comment section

Public stigma is what you hear from the outside: jokes, stereotypes, casual dismissal, fear. Self-stigma is what happens when

those messages move in, take your spare key, and start rearranging your furniture.

Self-stigma sounded like:

- “If I need help, I’m failing.”

- “If I tell anyone, they’ll see me differently.”

- “If I take medication, it means I’m broken.”

- “If I’m struggling, I’m a burden.”

And because I used to believe these things about other people, I believed them about myself with the confidence of someone

reading a horoscope and calling it a strategic plan.

The irony is brutal: the moment I needed compassion, my internal script offered me a courtroom drama.

What mental illness actually looks like (spoiler: mostly like people)

One reason mental health stigma persists is because mental illness doesn’t always “look like” what pop culture trained us to expect.

Many people with depression go to work. Many people with anxiety host parties. Many people with bipolar disorder, PTSD, OCD,

or schizophrenia are navigating treatment, relationships, and responsibilitiesoften while managing symptoms the rest of us can’t see.

Anxiety and depression aren’t rare guest stars

National surveys show that symptoms of anxiety and depression are common among U.S. adults. That doesn’t mean everyone has

a diagnosable disorder, but it does mean a lot of people are walking around with real distress behind polite smiles and “I’m fine.”

Violence myths are stickyand largely wrong

A damaging stereotype says people with mental illness are dangerous. In reality, major mental health organizations note that people

with mental illness are more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators. When we treat mental illness like a threat, we justify fear,

isolation, and policies that punish instead of support.

Language matters more than we want to admit

I used to toss around words like “psycho,” “bipolar,” or “OCD” as jokes or adjectives. After my own diagnosis journey began, those

words didn’t feel edgy; they felt like tiny paper cutsespecially when they came from people who otherwise considered themselves kind.

A simple shift helps: describe what you mean without turning someone’s health condition into a punchline. The goal isn’t perfection.

It’s reducing harm.

Work, school, and the art of not oversharing

One of the scariest questions I faced wasn’t “What’s wrong with me?” It was “What happens if people find out?”

In the U.S., mental health conditions can qualify as disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) when they substantially

limit major life activities. That matters because it means protections against discrimination and access to reasonable accommodations at work.

You don’t have to announce your entire life story to request support. You can ask for changes that help you perform your job.

Examples of reasonable accommodations that aren’t dramatic

- Flexible scheduling for therapy appointments

- Temporary remote work or hybrid arrangements (when feasible)

- Quiet workspace or noise-reducing options

- Clear written instructions and priorities during high-symptom periods

- Modified break schedules to manage panic or medication side effects

The point isn’t special treatment. It’s equal accesslike a ramp for a wheelchair, but for the days your brain is running

Windows 95 in a 5G world.

Treatment: the boring, beautiful stuff that works

I wish recovery looked like a cinematic montage: sunrise jogs, inspirational music, instant transformation, flawless skin.

In reality, it looked like filling out intake forms and learning that my “coping skills” were mostly sarcasm and iced coffee.

Evidence-based treatment often includes therapy, medication, lifestyle supports, and social connection. Different conditions respond

to different approaches, and what works can take time to dial in. The least glamorous truth is also the most hopeful one:

mental health conditions are treatable, and many people improve with proper care.

Therapy isn’t just “talking”it’s training

Good therapy taught me patterns: how avoidance feeds anxiety, how rumination pretends to be problem-solving, how sleep and stress

are basically co-workers who hate each other but share a desk in my body. I learned to name what was happening without turning it into

a moral failure.

Medication isn’t a personality transplant

I used to think psychiatric medication would turn someone into a zombie or a “different person.” For many people, it’s closer to glasses:

it doesn’t change who you areit helps you function with less distortion. Finding the right medication (or deciding not to use it) should be

done with a qualified clinician, and it can take adjustment.

Crisis support exists for a reason

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger or considering self-harm, call 988 in the U.S. for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline,

or call 911 for emergencies. If you’re not sure “counts” as a crisis: it counts. Your life is not a debate club topic.

How to talk to someone without accidentally being a human grenade

When I finally opened up to a few people, I learned something: most folks want to help, but stigma makes them weird.

They either overcorrect into baby-talk or panic and offer solutions like “Have you tried yoga?” (I have tried yoga. My anxiety can do yoga too.)

What helps

- Believe them. “That sounds really hard. I’m glad you told me.”

- Ask what support looks like. “Do you want advice, distraction, or just company?”

- Offer specifics. “I can drive you to your appointment” beats “Let me know if you need anything.”

- Stay connected. A text next week matters as much as a text today.

What hurts (even if you mean well)

- “Everyone feels that way sometimes.” (True, and also not helpful.)

- “Just think positive.” (If that worked, therapists would be out of business.)

- “You don’t seem depressed/anxious.” (Congrats, you met their mask.)

- “What do you have to be sad about?” (Ah yes, the Gratitude Court.)

You don’t need perfect words. You need presence, respect, and the willingness to treat mental health like health.

So… what changed?

I didn’t become a saint. I didn’t achieve permanent inner peace. My brain still occasionally tries to convince me that an unanswered email is

a federal crime. But I stopped believing the most damaging lie: that mental illness is a character defect.

Now when I hear someone say “mentally ill people are…” I flinch, not because I’m fragile, but because I know how fast a label can become a cage.

Stigma turns complexity into caricature. Recovery starts when we refuse to do thatto others or to ourselves.

And if you’re reading this thinking, Okay, but what if I’m the one who’s struggling?welcome to the club none of us asked to join.

The membership perks are questionable, but the people are surprisingly good. And you deserve care, not shame.

500 more words: the after-party of becoming “one of them”

The strangest part of developing a mental health condition wasn’t the symptoms. It was the social math. Suddenly I was calculating how every

sentence might be interpreted. If I said I was tired, would people hear “lazy”? If I said I was overwhelmed, would they hear “unstable”?

If I said I was in therapy, would they hear “unreliable”?

I became fluent in translation. “I have a medical appointment” meant “therapy.” “I’m dealing with some health stuff” meant “my nervous system has

unionized.” “I can’t make it tonight” meant “if I put on real pants, I might cry in public, and I’d prefer not to make that my brand.”

What surprised me most was how often people responded with their own hidden chapters. The moment I said, quietly, “I’ve been struggling,” it was as if

a secret door opened and everyone had a story behind it. A friend who’d been on medication for years. A coworker who’d had panic attacks in the bathroom

between meetings. A family member who’d carried grief like a backpack full of bricks and never called it anything but “being fine.”

That’s when I realized stigma thrives on silence. When we don’t talk about mental health, we fill the gap with stereotypes. We assume the worst. We

picture extremes. We imagine “the mentally ill” as a different category of human. But when people speak, the category breaks. It turns back into faces,

routines, and ordinary bravery.

Recovery also forced me to rethink “strength.” I used to think strength was staying functional no matter whatshow up, grind, succeed, repeat. Now I think

strength is noticing when you’re not okay and doing something about it before your life becomes a controlled burn. Strength is taking your own pain

seriously enough to treat it. Strength is learning how to rest without calling yourself a failure.

I won’t romanticize it. There were awkward conversations. There were people who got uncomfortable, changed the subject, or offered advice like a fortune cookie.

There were days I felt like I was watching life through a window. And yes, there were moments when I judged myself with the same harshness I once aimed at others.

Old beliefs don’t vanish; they fade like bad wallpaperslowly, and with a lot of peeling.

But there were wins, too. The first time I recognized a spiral and interrupted it. The first time I asked for help without apologizing for existing. The first time

I set a boundary and didn’t immediately write a 12-paragraph explanation. The first time I realized my diagnosis wasn’t a prophecyit was information.

If I could go back and talk to the earlier version of methe one with “reasonable opinions” and zero lived understandingI’d say this: mental illness is not a

punchline, a weakness, or a moral failure. It’s a health condition. It can happen to anyone. And the best time to drop the stigma is before you need the compassion

yourself. The second-best time is now.