Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Skill vs. Luck Is the Question Behind So Many Bad Decisions

- The “Success Equation”: Outcomes Live on a Continuum

- The Paradox of Skill: When Everyone Gets Better, Luck Looms Larger

- How to Diagnose Skill vs. Luck in the Wild

- Investing: The Ultimate Skill-and-Luck Blender

- Business and Strategy: When Copying Winners Backfires

- A Practical Playbook: How to Get Better in Luck-Heavy Domains

- Common Misreads (and How to Avoid Them)

- Experiences You Can Use to Actually Feel the Skill-vs.-Luck Distinction

- Conclusion: The Goal Isn’t to Be RightIt’s to Be Less Foolish

If you’ve ever watched someone hit a buzzer-beater, launch a startup, or pick a stock that doubles, you’ve probably said

something like: “Genius.” And sometimes that’s true. Other times… it’s just the universe rolling dice while we clap

like trained seals.

Few modern thinkers have done more to separate the “wow, impressive” from the “wow, improbable” than Michael Mauboussin.

In his work on decision-making and performanceespecially in The Success Equationhe argues that most outcomes

are a blend of skill and luck. The problem is we’re hilariously bad at knowing the mix.

We over-credit winners, over-punish losers, and build confident stories on top of tiny sample sizes (because our brains

hate uncertainty the way cats hate bath time).

This article breaks down Mauboussin’s core ideas on skill vs. luck, why the distinction matters in investing and business,

and how to build a more reality-based way to judge performancewithout becoming a joyless robot who refuses to celebrate

anything until the statistical significance shows up.

Why Skill vs. Luck Is the Question Behind So Many Bad Decisions

Skill matters because it’s repeatable. Luck matters because it’s unavoidable. Confusing the two is how you end up:

- Promoting the wrong person (and then acting shocked when the “rockstar” flames out).

- Copying a competitor’s strategy that “worked” (because you mistook good timing for good judgment).

- Chasing last year’s top-performing fund (the financial equivalent of buying snow boots in July).

- Learning the wrong lessons from wins and losses (a.k.a. outcome bias with a side of ego).

Mauboussin’s point isn’t that skill doesn’t exist. It’s that outcomes are noisy signals. If you want to

improve decisions, you need a framework that respects randomnessespecially in complex systems like markets, competitive

industries, and fast-moving careers.

The “Success Equation”: Outcomes Live on a Continuum

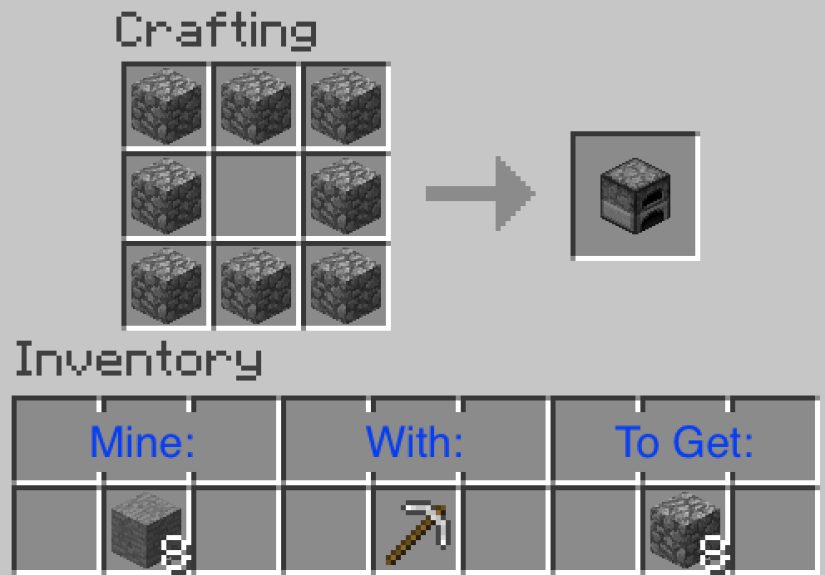

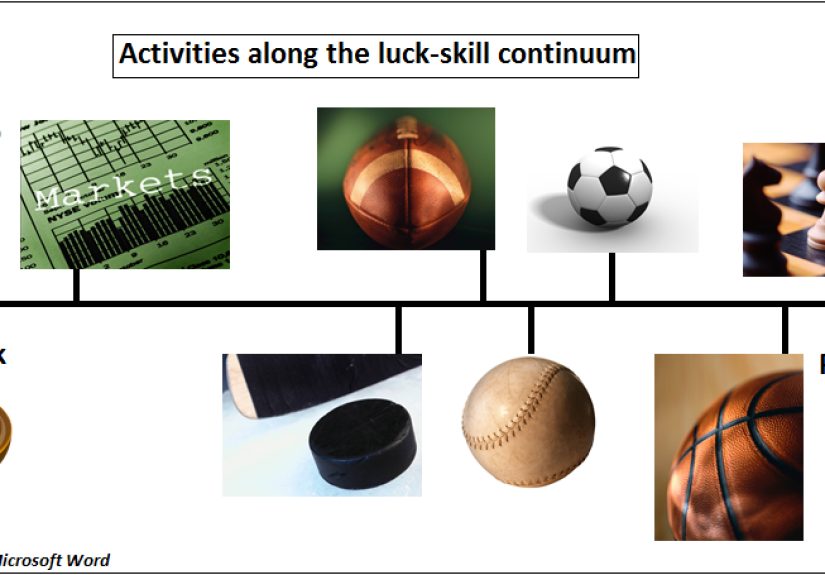

One of Mauboussin’s most useful contributions is a simple mental model: outcomes sit on a spectrum between

pure luck and pure skill.

At the extremes, life is easy

- Pure luck: Lottery tickets, roulette. You can have strategies, rituals, and a lucky hat… but the wheel does not care.

- Pure skill: Activities where ability dominates and better performers win consistentlythink of tasks with stable rules and repeatable execution.

Most real-world activities fall in the messy middleespecially business and investingwhere skill influences outcomes

but randomness still swings results. That’s where people get fooled, because the human brain sees a winner and starts

writing a movie script called “I Knew It All Along”.

A quick (and slightly savage) test: “Can you lose on purpose?”

A popular heuristic often highlighted in discussions of Mauboussin’s work is this: if you can intentionally perform

worsemiss a shot, play a suboptimal move, throw the gamethen skill is involved. If you can’t (try “losing on purpose”

at roulette), then it’s mostly luck.

It’s not a perfect test, but it’s a great way to jolt your intuition into recognizing that not every win is evidence of mastery.

The Paradox of Skill: When Everyone Gets Better, Luck Looms Larger

Here’s the idea that makes Mauboussin’s framework especially powerful (and mildly humbling): as skill rises in a field,

outcomes can become more dependent on lucknot because skill stops mattering, but because skill becomes

more evenly distributed.

Imagine a room full of amateur tennis players. The best one is probably going to crush the rest. Now imagine a room full

of elite pros. Everyone is excellent. Matches can hinge on a bad line call, a gust of wind, a slightly sore wrist, or a

net cord dribble that turns into a point. Skill still mattershugelybut the difference in skill is small enough that

randomness can decide who ranks first, second, or tenth.

In other words: the better the competition, the noisier the leaderboard.

That’s why it’s so hard to identify true, repeatable “best” performers in domains like professional investing, where

talent is abundant and information spreads fast.

How to Diagnose Skill vs. Luck in the Wild

Mauboussin emphasizes that you can’t label an activity “skill” or “luck” in the abstract. You have to look at the structure

of the game. Here are practical diagnostics you can use.

1) Look for stable rules and repeatable environments

The more stable the rules, inputs, and feedback loops, the more skill can compound. When the environment shifts constantly,

luck has more room to swing outcomes. Markets change. Competitors adapt. Technology rewrites the playbook. Skill still matters,

but the signal gets fuzzier.

2) Check the “sample size problem”

One of the fastest ways to embarrass yourself is to make big claims from small samples.

A CEO has two good quarters: “Visionary.” Two bad quarters: “Disaster.” In a luck-influenced domain, short runs tell you very little.

If you want to assess skill, you need:

- More observations (more decisions, more cycles, more seasons).

- Comparable conditions (so you’re not comparing sunny-day performance to hurricane-day performance).

- Risk adjustment (because swinging for the fences can look brilliant until it doesn’t).

3) Use transitivity as a “skill smell test”

In skill-heavy activities, performance is often transitive: if A reliably beats B, and B reliably beats C,

then A should reliably beat C. In luckier environments, you see more rock-paper-scissors cycles:

A beats B, B beats C, and C beats Abecause matchups, styles, and randomness matter more.

The more non-transitive the system, the less confidently you should interpret single outcomes as proof of superiority.

4) Watch how quickly “best practices” spread

When knowledge is cheap and widely available, skill compresses. That makes standout results harder to sustain.

If everyone learns the same techniques, competitive advantage shrinksand luck plays a bigger role in differentiating outcomes.

5) Pay attention to payoff distributions

Some domains have fat tails: a few extreme winners, many losers, and outcomes that are highly sensitive to timing and randomness

(think venture capital, blockbuster entertainment, or viral products). In these environments, luck can dominate the distribution

even when skill is present.

Investing: The Ultimate Skill-and-Luck Blender

Investing is where Mauboussin’s framework really earns its keep, because markets are competitive, adaptive, and noisy.

The paradox of skill shows up fast: lots of smart people, lots of data, similar tools, similar incentivesso even skilled

investors can look mediocre for long stretches, and lucky investors can look brilliant just long enough to get interviewed.

Why short-term performance is a terrible lie detector

Over short horizons, investing outcomes are dominated by:

- Macro surprises (rates, inflation, geopolitics, policy shifts).

- Sentiment swings (fear, FOMO, narrative contagion).

- Liquidity and positioning (flows can move prices regardless of fundamentals).

- Random clustering (streaks happen even when nobody has special powers).

That doesn’t mean skill is absent. It means you should judge skill by process and probabilistic thinking,

not by whether someone dunked on the market this quarter.

Streaks: sometimes evidence, often noise

One way to think about skill is to compare real-world results to what you’d expect under a “no-skill” model.

If you observe far more long winning streaks than randomness would generate, that suggests some managers may have repeatable advantages.

But even then, the practical question remains: can you identify them in advance, and can they persist after fees, competition,

and changing conditions?

The mature takeaway is not “skill doesn’t exist.” It’s: don’t confuse a hot hand with a durable edge.

Business and Strategy: When Copying Winners Backfires

In business, we love success stories. We read case studies like they’re cookbooks: “Do Step 1, then Step 2, then become

a unicorn by Tuesday.” The problem is that business outcomes often involve:

- Competitor reactions (your plan changes their plan).

- Shifting customer preferences.

- Technology shocks.

- Path dependence (tiny early events snowball into massive differences later).

That’s why Mauboussin urges caution with narratives. A company may succeed because of great decisions, but also because

it chose the right market at the right moment, avoided a landmine by luck, or benefited from a trend no one fully controlled.

If you copy the visible moves without the invisible context, you may recreate the costume… but not the magic trick.

The evaluation trap: rewarding outcomes, not decisions

Many organizations unintentionally train people to get lucky. If you promote based on outcomes alone, you encourage:

- Risk hiding (people avoid smart bets that might look bad short-term).

- Storytelling over learning (people sell narratives instead of improving decisions).

- Outcome bias (good process punished when it “fails,” bad process rewarded when it “works”).

A healthier culture scores decisions by what was known at the time, how alternatives were weighed, and whether the logic

matched the probabilitieseven if the outcome didn’t cooperate.

A Practical Playbook: How to Get Better in Luck-Heavy Domains

You can’t eliminate luck. But you can build systems that:

(1) make skill show up more often, and (2) prevent bad luck from wiping you out.

1) Separate “decision quality” from “result quality”

Ask two questions every time:

- Was the decision reasonable given the information and incentives?

- Did randomness play an outsized role in the outcome?

This simple split fights the urge to declare every win “proof” and every loss “failure.”

2) Demand larger samples before drawing big conclusions

In luck-influenced environments, single outcomes are anecdotesnot evidence.

Look for repeatability across time, contexts, and cycles. If the edge is real, it should show up in a pattern,

not just a highlight reel.

3) Use base rates and reference classes

Instead of asking “How amazing is this plan?” ask “How often do plans like this succeed?”

Base rates pull you away from wishful thinking and toward probabilistic realism.

4) Manage risk like you respect physics

Luck can be negative. If you take bets that can blow you up, eventually the universe will collect.

Good decision-makers survive long enough for skill to compound because they avoid catastrophic downside:

diversification, position sizing, margins of safety, and contingency planning aren’t boringthey’re how you stay in the game.

5) Build feedback loops that teach, not just judge

Learning requires feedback that’s timely and diagnostic. In domains where feedback is delayed (like long-term investing

or strategic business bets), you need deliberate tools: post-mortems, pre-mortems, and decision journals that capture

reasoning before outcomes distort memory.

Common Misreads (and How to Avoid Them)

Misread #1: “If skill exists, winners should always repeat.”

Not in luck-heavy domains. Skill can increase your odds and still produce losing streaks. The key is to think in

probabilities, not guarantees.

Misread #2: “If luck exists, nothing matters.”

Also wrong. Luck sets the noise level; skill improves your expected value. The goal is not certaintyit’s

better decisions that win more often over time.

Misread #3: “Confidence is evidence.”

Confidence is often just a good story told loudly. Evidence is repeatability, robustness, and a process that makes sense

under different scenarios.

Experiences You Can Use to Actually Feel the Skill-vs.-Luck Distinction

Frameworks are nice, but the real “aha” happens when you experience the difference between skill and luck in your own

decisions. Here are a few practical, low-drama experiments you can run in real lifeno lab coat required, and the only

electricity involved is the mild panic you feel when you realize your past certainty was not, in fact, a personality trait.

Experience 1: The Decision Journal That Roasts You (Lovingly)

For two to four weeks, pick a decision you make frequently: pricing a service, choosing marketing channels, hiring,

trading, even planning your weekly schedule. Before you decide, write down:

- What you believe will happen (include probabilities, not just vibes).

- What would change your mind (your “disconfirming evidence”).

- The key risks and how you’re managing them.

- What a reasonable alternative would be.

Then review outcomes later. The point is not to feel bad (although you may briefly consider moving to a cabin and

living off berries). The point is to see how often:

(a) a good decision had a bad outcome, or (b) a bad decision got rescued by luck. Over time, you’ll learn to respect

uncertainty and to improve the parts you actually controlyour research, your assumptions, your sizing, your timing,

and your contingency plans.

Experience 2: The “Same Strategy, Different Universe” Thought Experiment

Take one meaningful outcomesay, a successful project launch or a great investmentand replay it in your mind with

two small changes that could realistically have happened:

- A competitor launches two weeks earlier.

- A key employee gets sick during a critical week.

- Interest rates move in the opposite direction.

- A platform algorithm update hits your acquisition channel.

Ask: would your “skill story” still hold? If tiny, plausible changes flip the outcome, luck was doing more of the heavy

lifting than your victory speech admitted. This doesn’t erase your skill; it simply right-sizes your confidence and

pushes you toward building robustness (multiple channels, redundancy, better risk controls) instead of relying on

everything going right again.

Experience 3: Process Scoring (Because Outcome Scoring Lies)

Pick a recurring activity where you want to improve: sales calls, content creation, product iteration, portfolio decisions,

or team management. Create a simple process scorecard with 5–7 controllable inputs. For example:

- Did I gather the relevant information?

- Did I consider at least two alternatives?

- Did I check a base rate?

- Did I define what would prove me wrong?

- Did I size the bet appropriately?

- Did I document the rationale?

Score yourself weekly. You’ll notice something weird and wonderful: outcomes bounce around, but process quality can

steadily improve. And as process improves, you’ll often find outcomes become better over longer horizonseven if you

still get the occasional “perfect process, terrible result” week (hello, randomness). This experience trains you to

chase repeatability instead of applause.

Experience 4: The Humility DrillBet on Prediction Markets (or Just Your Own Forecasts)

Even if you never touch formal prediction markets, you can run a lightweight version: make ten forecasts about things

you care about (product metrics, deal close rates, market moves, hiring timelines). Put probabilities on them. Later,

check calibration: when you said 70%, did it happen about 70% of the time? Most people discover they’re either

overconfident (classic) or underconfident (rarer, but still a thing). Improving calibration helps you treat uncertainty

as a measurable variable rather than a vague feeling you suppress with optimism.

Put these experiences together and you’ll start to feel the Mauboussin lesson: success is often a cocktail of

skill and luck. Your job isn’t to deny luckit’s to build skillful processes, manage risk, and stay in the game long

enough for good decisions to pay off.

Conclusion: The Goal Isn’t to Be RightIt’s to Be Less Foolish

Michael Mauboussin’s work on skill vs. luck is ultimately a call for better judgment. If you operate in fields like

investing, business, leadership, or competitive performance, you’re living in a world where outcomes are informative

but not definitive. The cure is not cynicism. It’s process.

Celebrate winsjust don’t build your identity on them. Learn from lossesjust don’t assume they prove incompetence.

And when you evaluate people (including yourself), remember: the scoreboard is real, but it’s not always fair, and it’s

definitely not always telling you the whole story.