Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick Table of Contents

- 1) Bureaucracy is older than your inbox

- 2) People have always complained (with enthusiasm)

- 3) Law was about powerand paperwork proved it

- 4) Family life came with contracts, clauses, and consequences

- 5) Women show up as owners, signers, and decision-makers

- 6) Medicine mixed observation, tradition, and “please work” energy

- 7) Education was rigorous, repetitive, and full of practice drills

- 8) Religion and identity were debated in real time

- 9) Science wasn’t a modern inventionjust a modern job title

- 10) History is shaped by what survives (and what gets lost)

- Putting It All Together: What Ancient Documents Really Teach Us

- Bonus: Experiences Related to Ancient Documents (Extra ~)

- Conclusion

Ancient documents are basically humanity’s earliest “receipts”except instead of a crumpled CVS printout in your pocket, they’re clay tablets,

papyrus sheets, parchment manuscripts, and ink that somehow survived fires, floods, wars, and the occasional “oops, we used it to wrap fish.”

And because they’re primary sources (created by people who actually lived in the moment), they don’t just tell us what happenedthey show us

what people cared about: money, rules, family drama, medical worries, politics, faith, school… and yes, customer complaints.

Below are ten big insights we can pull from ancient texts and manuscriptsplus specific examples of the kinds of documents historians and

archaeologists use to build real-world pictures of the past. The fun part: a lot of it feels weirdly familiar. The humbling part: some of it is

familiar for reasons we wish weren’t.

Quick Table of Contents

- 1) Bureaucracy is older than your inbox

- 2) People have always complained (with enthusiasm)

- 3) Law was about powerand paperwork proved it

- 4) Family life came with contracts, clauses, and consequences

- 5) Women show up as owners, signers, and decision-makers

- 6) Medicine mixed observation, tradition, and “please work” energy

- 7) Education was rigorous, repetitive, and full of practice drills

- 8) Religion and identity were debated in real time

- 9) Science wasn’t a modern inventionjust a modern job title

- 10) History is shaped by what survives (and what gets lost)

- Bonus: Real-world experiences around ancient documents (extra ~)

1) Bureaucracy is older than your inbox

If you’ve ever sighed at a form that asks for information you already gave on the previous form, ancient documents have news for you:

bureaucracy didn’t start with modern governmentit’s basically an ancient invention with better branding now.

A huge portion of surviving ancient writing is administrative: tax lists, receipts, inventories, ration records, decrees, legal filings, and

“who owes what to whom” notes. These documents are not glamorous, but they’re gold. They prove that large societies ran on organization:

collecting resources, paying workers, recording land, tracking shipments, and keeping institutions accountable (or at least trying).

Concrete examples you see again and again

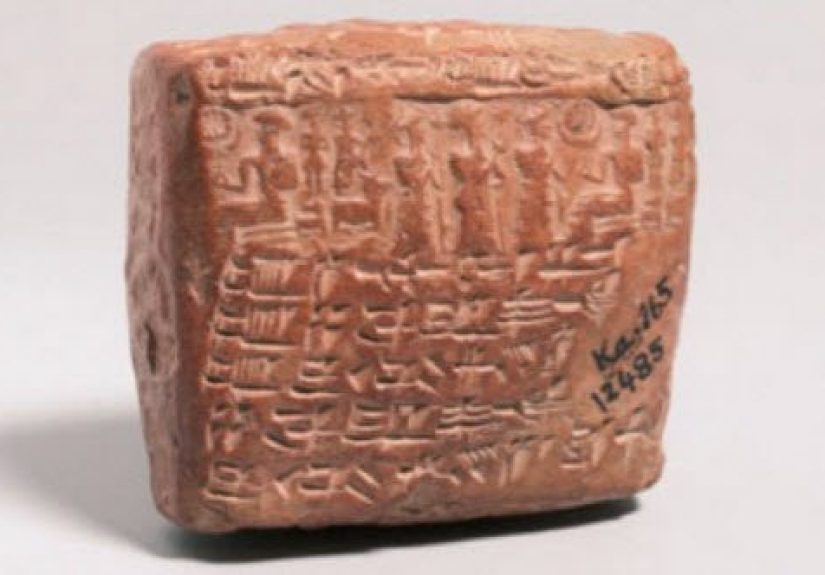

- Clay tablet archives from Mesopotamian cities that track temple and merchant activitysupplies, labor, deliveries, and payments.

-

Documentary papyri (not “fancy literature,” but everyday records) like letters, tax notes, marriage agreements, wills, and accounts.

The point is simple: everyday life left a paper trail… on papyrus. - Tax and land documents that list owners, workers, and obligationsbasically the ancient version of “your county knows exactly where you live.”

The takeaway: when you read an ancient tax list or warehouse inventory, you’re not reading boring stuffyou’re reading the operating system of a civilization.

2) People have always complained (with enthusiasm)

One of the most comforting insights in all of ancient writing is this: humans have been writing complaints for thousands of years.

The medium changes (clay tablet vs. one-star review), but the vibe is eternal.

Ancient letters and business documents show real customers arguing about quality, delivery delays, mistreatment, and broken promises. In other words,

the original “I would like to speak to the manager” wasn’t invented in a mallit was carved into clay.

Why this matters beyond the laughs

- It proves markets and trade relationships weren’t abstract conceptsthey were personal, emotional, and sometimes messy.

- It shows that trust was a big deal. Contracts and reputations mattered because people needed predictable exchange to survive.

- It gives us voices, not just events. Complaints are a direct line to how people felt when life went sideways.

Also, let’s be honest: it’s hard not to respect someone who took the time to turn frustration into a durable artifact.

Passive-aggressive? Maybe. Historically priceless? Absolutely.

3) Law was about powerand paperwork proved it

Ancient legal documentslaw codes, court records, contracts, and decreesteach an uncomfortable but crucial truth:

law is never just about justice. It’s also about power, social order, and whose version of “fair” becomes official.

A famous example often discussed in classrooms is the Code of Hammurabi, which lays out penalties and rules covering property,

labor, family matters, trade, and injury. It’s often remembered for harsh “eye for an eye” style punishments, but the bigger story is that it

shows a state trying to standardize expectations in a complex society.

What you learn by reading ancient law

- Society was stratified: penalties could differ depending on status and role.

- Commerce was central: disputes over goods, payments, and responsibilities were common enough to need rules.

- Public messaging mattered: law codes weren’t only practical; they also projected legitimacy (“this ruler brings order”).

The insight isn’t “ancient people had laws” (we knew that). The insight is that ancient laws reveal what a society feared, valued, and tried to control.

4) Family life came with contracts, clauses, and consequences

Ancient documents are full of relationship logistics. Marriage agreements, property settlements, divorce arrangements, wills, and inheritance notes

show that love (or at least cohabitation) often came with paperwork.

These records are especially powerful because they prove family life wasn’t only “private.” It had public consequences:

property moved through households, children’s status mattered, and disputes could ripple into economics and law.

Three surprisingly modern lessons

- Marriage was economic as well as personalcontracts often clarify obligations and assets.

- Divorce existed and required practical arrangements in many places and periods.

- Inheritance was a big deal because it determined stability, alliances, and survival.

If you’ve ever heard someone say, “It’s complicated,” ancient documents reply, “Correctand here are the terms and conditions.”

5) Women show up as owners, signers, and decision-makers

One of the most important (and frequently misunderstood) insights from ancient paperwork is that women appear in the record in concrete, legal ways.

Not everywhere, not equally, and not without limitationsbut often enough to correct the lazy myth that women were always invisible in public life.

Tax and land documents can list women as property owners. Marriage and property documents can outline financial protections.

Letters and receipts can show women participating in household economies. The effect is cumulative: ancient societies were diverse, and real life

didn’t always match the stereotype.

A practical reading tip

When you see a woman’s name in a legal or administrative text, don’t treat it as “an exception.” Treat it as data: a clue about law, economy,

and social structurethen look for patterns across multiple documents.

6) Medicine mixed observation, tradition, and “please work” energy

Ancient medical texts are a fascinating blend: you’ll see careful observation next to spiritual explanations; practical remedies next to rituals;

and serious attempts to help people next to… ideas that definitely would not pass a modern clinical trial.

The big insight isn’t “ancient medicine was bad” (that’s too smug and too simple). The insight is that ancient people were experimenting with

the tools they had: plants, minerals, procedural knowledge, and the best theories available at the time. Some approaches were surprisingly systematic.

What these texts reveal

- Patterns of illness and how communities explained them.

- Early pharmacology: repeated use of certain substances suggests long-term learning.

- Health priorities: which conditions were common enough to record and treat.

Reading ancient medical documents is like opening an old toolbox: some tools are outdated, some are strangely familiar, and the whole thing tells you

how hard people worked to keep each other alive.

7) Education was rigorous, repetitive, and full of practice drills

Ancient schoolwork survives in the most relatable way possible: practice texts. Scribal students copied symbols, repeated lines, corrected mistakes,

and worked through staged learning. Translation: ancient students had homework too. Human progress is beautiful. Also, sorry.

Practice tablets and instructional texts show how literacy was taught, how specialized scribes were trained, and why writing carried status.

If you controlled writing, you controlled administration, contracts, and knowledge transfer.

What “student exercises” teach us

- Education systems existed with structured progression.

- Standardization mattered: writing had conventions, not just creativity.

- Literacy was power: scribes didn’t just writethey enabled governments, trade, and law.

8) Religion and identity were debated in real time

Ancient religious documentsrules, commentaries, hymns, and community textsshow that belief wasn’t a single frozen thing. People argued about meaning,

identity, correct practice, and which texts mattered. In other words: debates over interpretation are not a modern internet invention.

Manuscript discoveries associated with communities and libraries (including famous caches of scrolls and fragments) reveal multiple versions of texts,

evolving traditions, and a living culture of copying, preserving, and interpreting writings.

Why this insight matters

- It highlights diversity within traditions, not just differences between them.

- It shows how communities define themselvesby rules, stories, and shared documents.

- It proves that texts have histories: copying and transmission are part of the story.

9) Science wasn’t a modern inventionjust a modern job title

Ancient technical textsespecially mathematical and astronomical recordsshow serious, cumulative reasoning. People tracked cycles, predicted events,

and built methods that required careful calculation and long-term observation.

Clay tablets with astronomical content, for example, demonstrate that ancient scholars could use sophisticated approaches to understand planetary motion.

Whether we call that “science” depends on definitions, but the intellectual labor is unmistakable: repeated measurement, pattern recognition, and

method-building over generations.

What this changes in your mental timeline

- Innovation is not a straight line; it’s a relay race.

- “Pre-modern” doesn’t mean “pre-smart.”

- Documents preserve process, not just resultsand process is where the genius hides.

10) History is shaped by what survives (and what gets lost)

Here’s the most important meta-insight: ancient documents don’t give us “the whole past.” They give us the past that survived.

And survival can be random: a text might endure because it was stored, buried, recycled into a binding, or accidentally preserved by disaster.

That means historians must constantly wrestle with gaps, bias, and incomplete evidence.

This is why “primary sources” are powerful but tricky. They’re direct evidence, yesbut they’re also partial. One archive can represent a whole

institution; one cache can reshape what we think we know. Reading ancient documents responsibly means asking:

Who wrote it? For what purpose? Who got left out? What other documents would we need to confirm the picture?

How to use this insight as a reader

- Be curious about context: where a document was found and how it was used.

- Watch for purpose: administrative texts differ from propaganda, letters differ from law codes.

- Expect translation limits: fragments, damaged surfaces, and ambiguous words are normal in ancient materials.

The best part? This detective work is exactly why ancient documents stay exciting. They’re not just “old texts.” They’re puzzles with real stakes.

Putting It All Together: What Ancient Documents Really Teach Us

If you only remember one thing, make it this: ancient documents don’t just tell stories about kings and wars. They show everyday systemsrules,

work, family, trade, education, belief, and problem-solving. In clay and ink, you can watch humans invent the structures we still live inside.

And yes, you’ll also find timeless comedy: complaints, misunderstandings, anxious letters, dramatic legal wording, and “I swear this was a reasonable idea”

energy scattered across centuries. The past wasn’t a museum. It was a neighborhoodbusy, loud, complicated, and full of people trying to get through the week.

Bonus: Experiences Related to Ancient Documents (Extra ~)

If you’ve never interacted with ancient documentsbeyond seeing a scroll behind glasshere’s what people often experience when they finally

get close to the real stuff (in museums, archives, libraries, classrooms, or even high-resolution digital collections). It’s less like reading a book

and more like meeting a person who speaks in fragments.

First comes the scale surprise. Many ancient documents are smaller than expected: a tablet you imagined as “tablet-sized” might be closer

to “fits in your palm.” That physical reality changes your thinking immediately. A letter that small wasn’t meant to be majesticit was meant to be handled,

passed, stored, and used. Suddenly, “history” stops being abstract and starts feeling like someone’s workday.

Then comes the texture of time. People who work with manuscripts often describe a moment of quiet awe when they realize:

this ink stroke (or wedge mark) was made by a real hand. Not a symbol of a hand. A hand. The same kind of hand that would wave you over, carry a basket,

or point at a mistake and say, “No, not like that.” It’s oddly groundinglike time is long, but humans are consistent.

Next, you hit the translation reality check. If you’re reading in modern English, you’re reading decisions made by translators:

how to handle idioms, missing pieces, uncertain words, and cultural references that don’t map neatly to today. Students and casual readers often feel

two emotions at once: gratitude that the text is accessible, and suspicion that something important is hiding in the parts that are hard to render.

(That suspicion is healthy. It keeps you honest.)

Many researchers talk about the fragment frustration. Ancient documents are frequently damaged: holes, cracks, faded ink, broken corners.

You might get 80% of a letter and lose the one sentence that explains everythinglike reading a mystery novel where the last page is missing.

The upside is that you learn to love cautious language: “likely,” “suggests,” “may indicate,” “in this context.” It’s not weakness; it’s precision.

Another common experience is the everyday-life jolt. People expect ancient writing to be solemn. Then they read a mundane receipt,

a household list, a complaint, or a family noteand realize the past was packed with errands. That’s when ancient documents deliver their best lesson:

civilizations weren’t built only by big speeches. They were built by someone writing down who received grain, who owed copper, who inherited land,

and who needed help right now.

Finally, there’s the perspective shift. Once you’ve spent time with ancient documentsespecially a variety of themyou start noticing

how much modern life depends on recordkeeping. IDs, contracts, bills, medical notes, school transcripts, messages. We’re still living in a world made of documents.

The difference is that ours come with passwords and pop-ups instead of seals and scribes. Progress!

Conclusion

Ancient documents are more than artifactsthey’re evidence. They reveal how societies organized money, enforced rules, negotiated family life,

treated illness, taught students, practiced belief, and pursued knowledge. They also reveal something wonderfully persistent:

people have always been resourceful, complicated, occasionally dramatic, and deeply invested in fairness (especially when it benefits them).

So the next time you see a tablet, papyrus, or manuscript described as “fragmentary,” don’t hear “incomplete.” Hear “alive.”

Even a fragment can carry a full human voice across thousands of yearsno Wi-Fi required.