Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Chapter 1: What Is Aortic Stenosis (and Why Your Heart Cares)?

- Chapter 2: Causes of Aortic Stenosis (How the Door Gets Stiff)

- Chapter 3: Symptoms (The Classic Trio… Plus the “Sneaky” Ones)

- Chapter 4: Diagnosis (How Doctors Confirm What’s Going On)

- Chapter 5: Treatments (What Helps, What Doesn’t, and What Actually Fixes It)

- Chapter 6: What to Expect With TAVR or Surgery (The Human Version)

- Chapter 7: A “Video Chapter Guide” You Can Use as a Script

- Chapter 8: Frequently Asked Questions (Because Google Is Loud)

- Conclusion: The Big Takeaway (in One Breath)

- Real-World Experiences (): What People Commonly Report Living With Aortic Stenosis

Imagine you just hit “play” on a clear, reassuring health videoone that explains what’s going on, what to watch for,

and what your options are (without yelling in all caps). This article is built like that video: chapter-by-chapter,

plain-English, and focused on real-life decisions patients and families face with aortic stenosis.

Quick note: This is educational content, not personal medical advice. If you have chest pain, fainting, severe shortness of breath,

or stroke symptoms, seek emergency care right away.

Chapter 1: What Is Aortic Stenosis (and Why Your Heart Cares)?

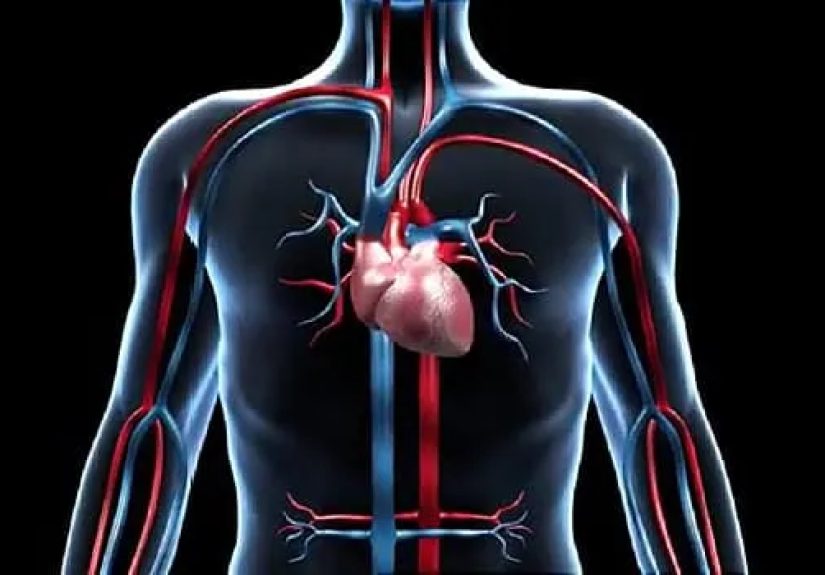

Aortic stenosis means the aortic valveyour heart’s “front door” for blood heading to the bodyhas become narrowed and doesn’t open as well.

When that door gets stiff, your heart has to push harder to get blood out. Over time, that extra work can lead to thickened heart muscle,

symptoms with activity, and eventually heart failure if severe disease isn’t treated.

What the valve actually does

The aortic valve sits between the left ventricle (the main pumping chamber) and the aorta (the big highway artery to the rest of you).

A healthy valve opens wide with each heartbeat and then closes tightly to prevent backflow.

In aortic valve stenosis, the opening becomes smallerso less blood can move forward with each beat.

Why many people feel “fine” for a long time

Aortic stenosis often develops slowly. Your heart is a champion at compensatinguntil it isn’t.

That’s why some people have significant narrowing on an echocardiogram but minimal symptoms early on.

The goal is to catch progression before it turns into a “sudden plot twist” during a walk, workout, or grocery run.

Chapter 2: Causes of Aortic Stenosis (How the Door Gets Stiff)

Aortic stenosis isn’t usually caused by something you did last weekend. It’s most often related to aging changes in the valve,

congenital anatomy, or past inflammatory damage.

Age-related calcification (the most common cause in adults)

Over years, calcium can build up on valve leaflets, making them thicker and less flexible. Think of it like mineral buildup on a faucet

except the faucet is your heart valve, and you definitely can’t soak it overnight in vinegar (please do not attempt).

Bicuspid aortic valve (born with two leaflets instead of three)

Some people are born with an aortic valve that has two leaflets (bicuspid) rather than three. That valve may wear out faster,

developing stenosis earlier in life. This is one reason aortic stenosis isn’t only an older-adult condition.

Rheumatic heart disease and other less common causes

Prior rheumatic fever can damage valves and contribute to stenosis. Less commonly, prior chest radiation, chronic kidney disease,

or other conditions may accelerate valve calcification or scarring.

Risk factors that can stack the deck

- Older age

- High blood pressure

- High LDL cholesterol

- Smoking history

- Diabetes

- Chronic kidney disease

- Family history of bicuspid valve or early valve disease

Chapter 3: Symptoms (The Classic Trio… Plus the “Sneaky” Ones)

Symptoms often show up with exertion first, because that’s when your body demands more blood flow. When the valve opening is too tight,

the supply can’t keep up with demand.

The classic symptom trio

- Shortness of breath or reduced exercise tolerance (you get winded doing what used to be easy)

- Chest pain/pressure (especially with activity)

- Dizziness or fainting (syncope), often during exertion

Other symptoms people describe

- Unusual fatigue (the “why am I tired after a shower?” feeling)

- Heart palpitations or a fluttering heartbeat

- Swelling in ankles/feet (later-stage heart strain)

- Worsening sleep due to breathing discomfort

When to treat it like an emergency

Call emergency services if you have chest pain that doesn’t go away, fainting, severe shortness of breath at rest,

or sudden neurologic symptoms (face droop, arm weakness, speech trouble). Aortic stenosis can be seriousfast.

Chapter 4: Diagnosis (How Doctors Confirm What’s Going On)

Aortic stenosis is often suspected after a clinician hears a heart murmur, then confirmed and graded using imagingmost importantly,

an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart).

Echocardiogram: the main event

Echo measures how narrow the valve is and how much pressure builds as blood squeezes through it. It also evaluates:

heart muscle thickness, pumping function (ejection fraction), and whether other valves are affected.

Other tests you might see in a “full workup”

- Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG): looks for rhythm issues or strain patterns

- Chest X-ray: can show heart enlargement or lung fluid in advanced disease

- CT scan: may help assess calcification and anatomy (especially in procedural planning for TAVR)

- Exercise testing: sometimes used when symptoms are unclear (under specialist guidance)

- Cardiac catheterization: may evaluate coronary arteries before valve replacement

Why “severity” matters so much

Treatment decisions hinge on how severe the stenosis is and whether you have symptoms (or reduced heart pumping function).

Mild/moderate cases often require monitoring; severe casesespecially with symptomsoften require valve replacement.

Chapter 5: Treatments (What Helps, What Doesn’t, and What Actually Fixes It)

Here’s the key idea: medications can help symptoms and related heart issues, but they don’t “unstiffen” a severely narrowed valve.

The definitive treatment for severe, clinically significant aortic stenosis is usually valve replacement.

Watchful waiting (aka smart monitoring)

If you have mild or moderate stenosisor severe stenosis without symptomsyour care team may recommend periodic follow-ups,

repeat echocardiograms, and symptom tracking. This is not “doing nothing.” It’s timing an intervention for when it provides clear benefit.

Medicines (supportive, not curative)

Doctors may prescribe medications to manage blood pressure, fluid retention, rhythm problems (like atrial fibrillation),

or chest discomfort. The exact plan depends on your overall heart health and other conditions.

SAVR: Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement

SAVR is open-heart surgery to replace the narrowed valve. It has a long track record and may be preferred in certain patients,

especially when other heart repairs are needed at the same time.

Replacement valves can be:

- Mechanical: very durable, often requires long-term anticoagulation

- Bioprosthetic (tissue): typically avoids long-term warfarin for many patients, but may wear out over time

TAVR: Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

TAVR replaces the valve using a catheter (often through an artery in the groin) rather than open surgery.

For many patientsespecially older adults or those at higher surgical riskTAVR can offer a shorter recovery and less invasive approach.

A specialized “heart team” considers your age, anatomy, other illnesses, and personal preferences to help pick the best option.

Balloon valvuloplasty (a temporary helper)

Balloon valvuloplasty opens the valve by inflating a balloon inside it. In adults, the benefits may be temporary, so it’s often used as a bridge:

stabilizing someone before surgery/TAVR or in special situations where replacement isn’t immediately possible.

Chapter 6: What to Expect With TAVR or Surgery (The Human Version)

The “heart team” decision

Many centers use a team approach (interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, imaging, anesthesia, and more).

The decision isn’t just “Which procedure is cool?” It’s “Which option is safest and most durable for you?”

Before the procedure

- Imaging to map valve anatomy and blood vessels

- Medication review (especially blood thinners)

- Coronary artery evaluation (some patients need stents or bypass planning)

- Discussion of recovery goals, home support, and rehab

Recovery basics

Recovery time varies by procedure and person. Many people feel improvement in breathing and stamina after a successful valve replacement,

but rebuilding strength can take weeks to months. Cardiac rehab may help you regain endurance safely.

Long-term follow-up

After valve replacement, follow-up visits and periodic imaging matter. You may also receive guidance on dental care and infection prevention,

because valve infections (endocarditis) can be serious. Always tell healthcare providers you have a valve replacement.

Chapter 7: A “Video Chapter Guide” You Can Use as a Script

If you’re creating or evaluating a patient education video on aortic stenosis, this chapter list keeps it clear, accurate, and not overwhelming.

Suggested chapters (with optional timestamps)

- 00:00–00:30 What aortic stenosis is (one-sentence definition + simple valve diagram)

- 00:30–01:30 Causes: calcification, bicuspid valve, rheumatic disease

- 01:30–02:30 Symptoms: shortness of breath, chest pain, fainting + fatigue

- 02:30–03:20 Diagnosis: murmur, echocardiogram, staging/severity

- 03:20–04:40 Treatments: monitoring, meds for symptoms, SAVR vs TAVR

- 04:40–05:30 What recovery looks like (hospital stay, rehab, follow-up)

- 05:30–06:00 Red flags + questions to ask your cardiologist

One-minute sample voiceover (friendly, not scary)

“Aortic stenosis is when the valve that lets blood leave your heart becomes narrowed. Your heart can compensate for a long time,

but as the valve tightens, you might notice shortness of breath, chest pressure, dizziness, or getting tired more easily.

Doctors diagnose it with an echocardiograman ultrasound that measures how well the valve opens and how hard your heart has to push.

Medications can help symptoms, but severe aortic stenosis is usually treated by replacing the valve, either with surgery or a less invasive approach called TAVR.

The good news is that treatment can improve symptoms and quality of lifeespecially when the timing is right.”

Chapter 8: Frequently Asked Questions (Because Google Is Loud)

Can I exercise if I have aortic stenosis?

Many people with mild or moderate stenosis can stay active, but the safest plan depends on severity and symptoms.

If you have chest pain, dizziness, fainting, or severe shortness of breath with activity, stop and talk to your clinician promptly.

How fast does it get worse?

Progression varies. Some people remain stable for years; others progress more quickly. That’s why repeat echocardiograms and symptom tracking are important.

If your “normal walk” is getting shorter, that counts as useful medical informationtell your care team.

Is there a diet that fixes the valve?

No diet can reverse a severely narrowed valve. However, heart-healthy eating supports blood pressure, cholesterol, and overall cardiovascular health,

which can make treatment safer and recovery smoother.

What questions should I ask at my appointment?

- How severe is my aortic stenosis right now?

- What symptoms should trigger a call or ER visit?

- How often do I need an echocardiogram?

- Am I a candidate for TAVR, SAVR, or both?

- What are the benefits and risks for someone with my age and health profile?

Conclusion: The Big Takeaway (in One Breath)

Aortic stenosis is a narrowing of the aortic valve that can quietly progress until symptoms appearoften during exertion.

Diagnosis centers on echocardiography, and while medications can support symptoms and related heart issues, severe disease is typically treated with valve replacement,

either surgically (SAVR) or via catheter-based approaches (TAVR). The best outcomes come from recognizing symptoms early, monitoring severity,

and making a shared decision with a heart team about the right treatment at the right time.

If you’re using this as a “video companion,” remember the goal isn’t to memorize every termit’s to recognize the warning signs,

understand the pathway from diagnosis to treatment, and feel prepared to ask good questions.

Real-World Experiences (): What People Commonly Report Living With Aortic Stenosis

People often describe aortic stenosis as “not dramatic, just limiting”until it suddenly feels dramatic. One common experience is

the slow shrinkage of your personal “comfort zone.” At first, you might notice you’re breathing harder on stairs, or you need a break

after carrying groceries. Because it happens gradually, many folks assume it’s aging, stress, being “out of shape,” or a bad sleep streak.

In reality, the heart may be working overtime to push blood through a narrowed valve, and your body is quietly adapting by doing less.

Another theme is the “I didn’t know I had symptoms until I felt better” moment. Some patients realizeafter valve replacementthat

they had been living at 70% for years. They’ll say things like, “I thought everyone got winded like that,” or “I forgot what normal energy felt like.”

Caregivers notice this too, often before the patient does: walking slower, avoiding hills, skipping activities, or needing more rest days.

That outside perspective can be incredibly helpful when symptoms are subtle.

The diagnostic experience can feel oddly simple: someone hears a murmur, an echocardiogram is ordered, and suddenly there’s a clear name

for the problem. People report mixed emotionsrelief (finally an explanation), worry (the word ‘severe’ is never anyone’s favorite),

and confusion about timing (“If I feel okay, why are we talking about a procedure?”). Clinicians usually emphasize that symptom status and heart function

guide decisions, and that waiting too long in severe symptomatic aortic stenosis can raise risks.

When it comes to treatment, decision-making can feel like learning a new language: SAVR, TAVR, gradients, valve size, risk scores, durability.

Many people find it helpful to bring a list of questions and a second set of earsbecause your brain will absolutely forget half the discussion

the moment someone says “catheter” (totally normal). Patients who go through a heart-team approach often appreciate hearing the reasoning:

“Here’s why we think TAVR fits your anatomy and goals,” or “Here’s why surgery makes sense because we also need to address another issue.”

Recovery stories vary, but a consistent pattern is a gradual return of stamina. People describe the first few weeks as a “two steps forward, one nap back”

process. Cardiac rehab is frequently described as confidence-building: supervised exercise, education, and a safe way to rebuild endurance.

Emotionally, it’s also common to feel a wave of gratitudefollowed by impatience (“Why aren’t I 100% yet?”). A helpful mindset is progress over perfection:

improved breathing, longer walks, less dizziness, better sleep. Those wins add up.

Finally, many patients say the biggest lesson is learning to take symptoms seriously. If your body starts sending new signalsshortness of breath,

chest pressure, lightheadednesstreat that as useful information, not personal weakness. Your heart isn’t being lazy. It’s being honest.