Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What the report really found (and why “surging” isn’t hype)

- Why more kids and teens are being considered for surgery now

- What “weight-control surgery” means (and what it doesn’t)

- Who may qualify: the criteria in plain English

- Which procedures are most common for teens

- Benefits that go beyond the scale

- Risks, trade-offs, and what families don’t always hear in headlines

- Surgery vs. medications vs. lifestyle: it’s not a cage match

- Equity, access, and the uncomfortable truth about who gets treated

- Questions parents (and teens) should ask before saying “yes”

- Real-world experiences: what families and teens often go through (about 500+ words)

- Conclusion: what this “surge” should tell us

Not long ago, pediatric weight-loss surgery was treated like a unicorn: rare, mysterious, and only spotted in the distance by specialists with binoculars.

Now it’s showing up in real clinic schedulesand the data backs it up.

A new wave of research and updated medical guidance has pushed one idea into the mainstream of pediatric care: for some adolescents with severe obesity,

metabolic and bariatric surgery isn’t “extreme.” It’s evidence-basedand often life-changing. Still, it’s not a quick fix, not a cosmetic shortcut,

and definitely not a “see you at the mall after surgery” kind of decision.

Let’s break down what “surging” actually means, why it’s happening now, which teens may qualify, what procedures are most common, and what families should know

before anyone even thinks about signing a consent form.

What the report really found (and why “surging” isn’t hype)

The headline is attention-grabbing, but the story is mostly about trendsand access. In national surgical registry data analyzed by researchers,

the number of metabolic and bariatric surgery procedures among U.S. youth ages 10 to 19 rose steadily in recent years. One notable jump occurred

from 2020 to 2021, when youth procedures increased by about one-fifth.

That rise shows up not only in total counts but also across racial and ethnic groups. And it matters because it suggests something bigger than a sudden

“fad”: more clinicians are referring, more families are asking, and more systems are building pediatric programs that can actually support teens long-term.

Here’s the most important context: even with a surge, adolescent bariatric surgery remains a small slice of all bariatric procedures in the United States.

Millions of young people meet clinical criteria, yet only a tiny fraction undergo surgery each year. So “surging” does not mean “common.”

It means “rising from very low levels.”

Why more kids and teens are being considered for surgery now

1) Severe obesity is risingand it’s not just a “future problem”

Childhood obesity isn’t a new issue, but severe obesity is a different beast. It tends to come with earlier and more serious complicationslike type 2 diabetes,

high blood pressure, sleep apnea, fatty liver disease, and joint problemssometimes before a teen even gets a driver’s license.

Public health data show obesity affects a substantial portion of U.S. children and teens, with prevalence increasing with age. That means pediatric clinics

are seeing more adolescents whose weight is already impacting daily function and long-term health risk.

2) Medical guidance shifted away from “wait and see”

For years, “watchful waiting” was common: encourage healthier habits, hope adolescence “stretches it out,” and revisit later. But obesity is now widely framed

as a complex, chronic diseaseshaped by biology, environment, medications, sleep, stress, mental health, and social determinants of health.

Updated pediatric guidance emphasizes earlier, more intensive treatment. That includes structured lifestyle therapy, anti-obesity medications in selected adolescents,

and referrals for metabolic and bariatric surgery when criteria are met and less invasive treatments haven’t been enough.

3) We have stronger long-term outcomes data than we used to

One reason surgery discussions were historically cautious is that pediatric long-term data was limited. That’s changing. Large multi-center studies now follow teens

for many years after surgery, showing durable weight loss for many participants and meaningful improvements in obesity-related conditions.

In other words: this isn’t medicine “trying something wild.” It’s medicine responding to a chronic disease with a tool that has increasingly mature evidence

behind itwhen used appropriately.

What “weight-control surgery” means (and what it doesn’t)

“Weight-control surgery” is a broad, media-friendly phrase. Clinically, most modern adolescent procedures fall under

metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS). The “metabolic” part matters because the goal isn’t just weight loss;

it’s also improving metabolism and reducing disease risk.

This is not liposuction. It’s not a “tummy tuck.” And it’s not a punishment for liking pizza. MBS changes the digestive system in ways that affect

stomach capacity, hormones involved in hunger and fullness, andin some procedureshow the body absorbs nutrients.

Because these changes are powerful, surgery is typically reserved for adolescents with severe obesity, often alongside serious health complications

or significant impairment in quality of life.

Who may qualify: the criteria in plain English

Pediatric eligibility isn’t based on one number alone. Clinicians consider BMI (using pediatric growth charts), obesity class, comorbidities,

growth and development, mental health readiness, family support, and the ability to follow long-term nutrition and medical plans.

Common referral thresholds used in pediatric programs

-

Severe obesity often includes BMI at or above 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex (a pediatric measure),

or certain absolute BMI cutoffs used in clinical guidance. -

Class 2 obesity may qualify when accompanied by significant obesity-related comorbidities (examples: type 2 diabetes, moderate-to-severe sleep apnea,

fatty liver disease, hypertension, and others). - Class 3 obesity may qualify even without major comorbiditiesthough many teens at this level have them.

Age and the “whole-team” requirement

Many guidelines recommend considering referral for evaluation starting around age 13 for adolescents with severe obesity.

But “referral” doesn’t mean “automatic surgery.” It means meeting with a specialized, multidisciplinary teamtypically involving pediatric obesity medicine,

bariatric surgery, nutrition, mental health, and sometimes endocrinology, cardiology, or sleep medicine.

Think of it like this: the surgery is one part of treatment, but the program is the actual intervention. Surgery without long-term follow-up is like

buying a treadmill and using it as a clothes rack.

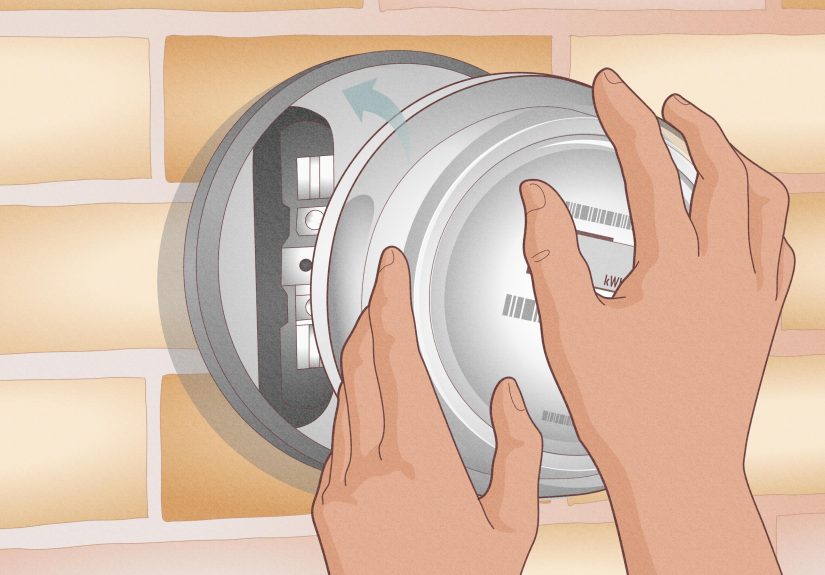

Which procedures are most common for teens

Sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy removes a portion of the stomach, leaving a smaller, tube-shaped “sleeve.” This reduces stomach capacity

and influences hunger-related hormones. It’s widely used in adolescents and has become the dominant procedure in many programs.

Sleeve surgery is often described as less complex than gastric bypass, and it may have a different nutritional risk profilethough it still requires

lifelong attention to vitamins, protein intake, and follow-up labs.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass creates a small stomach pouch and reroutes part of the small intestine. It can be especially effective for

improving blood sugar control and may be considered when reflux disease is a concern.

Bypass can offer strong metabolic benefits, but it also carries a higher risk of certain nutrient deficiencies and requires strict adherence to supplementation

and monitoring.

What about bands and balloons?

Adjustable gastric bands have fallen out of favor in many places due to lower long-term effectiveness and the need for re-operations.

Other devices may be restricted by age approvals and are less commonly used for adolescents in the U.S.

Benefits that go beyond the scale

For eligible teens, the most meaningful outcomes are often medicalnot cosmetic. Studies following adolescents for years after surgery show that many experience:

- substantial and sustained weight loss

- improvements in high blood pressure and cholesterol

- better control of blood sugar and, in some cases, remission of type 2 diabetes

- improvements in sleep apnea and breathing

- better mobility and less joint pain

- improved health-related quality of life

One reason pediatric experts take MBS seriously is that some conditionsespecially type 2 diabetescan progress aggressively in youth.

Earlier intervention can reduce years of exposure to high blood sugar and cardiovascular risk.

It’s also worth noting that teens can experience social and functional benefits that are hard to measure but real: easier participation in sports,

less fatigue climbing stairs, less pain, and sometimes improved confidence. Those gains don’t replace mental health care or fix stigma overnight,

but they can change a teen’s day-to-day experience in meaningful ways.

Risks, trade-offs, and what families don’t always hear in headlines

Surgery is not “easy mode.” It’s “new rules.” And it comes with real riskssome immediate, some long-term.

Short-term and surgical risks

Modern bariatric surgery is typically performed laparoscopically and is considered relatively safe in experienced centers,

but complications can still occur. These may include bleeding, infection, leaks, blood clots, or the need for additional procedures.

Centers reduce these risks with careful screening, standardized protocols, and follow-up.

Long-term nutritional risks

The most consistent long-term issue is micronutrient deficiency risk. Iron, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin D, calcium,

and others may fall over timeespecially without consistent supplements and lab monitoring.

Translation: bariatric surgery is a lifetime subscription to “vitamins, labs, and showing up.” If a teen (and family) can’t commit to that,

the program may recommend delaying surgery until they can.

Mental health and eating behaviors still matter

Surgery can change hunger and portion size, but it doesn’t erase stress, trauma, depression, anxiety, disordered eating,

or the emotional “why” behind some food patterns. That’s why good programs include mental health screening and support.

A successful outcome often looks like this: the teen’s medical risk drops, energy improves, and the family builds sustainable routines.

A risky outcome often looks like this: the scale drops quickly, follow-up fades, supplements stop, and problems show up quietly later.

Surgery vs. medications vs. lifestyle: it’s not a cage match

Families sometimes feel pressured to pick a “team”: lifestyle only, medication, or surgery. In reality, the best care is usually layered.

Intensive lifestyle treatment is still foundational

Evidence-based pediatric obesity care often starts with structured, family-based lifestyle therapynutrition coaching, activity planning,

sleep support, and behavior strategies. This isn’t “eat less, move more” tossed over the fence; it’s structured, coached, and sustained.

Anti-obesity medications are expanding optionsespecially GLP-1s

Medications (including GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide) have become more visible in adolescent care. They can reduce appetite and improve

metabolic markers, and some trials show meaningful BMI reductions in teens. But access, cost, supply, side effects, and the need for ongoing use

are real considerations.

Where surgery fits

Surgery tends to be considered when severe obesity is present and health risks are highor when other therapies haven’t produced adequate,

sustained improvement. For some teens, MBS offers the most durable metabolic change available today.

The healthiest framing is not “surgery as a last resort,” but “surgery as a toolused at the right time, for the right patient, in the right program.”

Equity, access, and the uncomfortable truth about who gets treated

Research suggests that use of adolescent bariatric surgery has increased across racial and ethnic groups, including Black and Hispanic youth.

That’s encouragingbut it doesn’t erase the bigger access story.

Barriers still include:

- limited availability of pediatric bariatric centers in some regions

- insurance hurdles and inconsistent coverage for surgery or required pre-surgical programs

- transportation, time off work, and family logistics for frequent visits

- stigma (including stigma inside healthcare settings)

- lack of referral pathways in primary care

A surge in surgeries may partly reflect improved accessbut it can also reflect greater need. And that’s the part worth sitting with:

the pipeline isn’t just “more surgery,” it’s “more severe disease showing up earlier.”

Questions parents (and teens) should ask before saying “yes”

- What qualifies my teen? Ask for the exact criteria the program uses and which comorbidities they’re targeting.

- What does the full treatment plan include? Nutrition, mental health support, activity planning, sleep, and follow-up schedule.

- Which procedure is recommended and why? Sleeve vs. bypass decisions should be individualized.

- What supplements and labs are requiredand for how long? (Hint: the answer is “for life.”)

- How does the program handle school, sports, and social life? Recovery and routine matter.

- What are the realistic outcomes? Ask about expected weight change, disease improvements, and what “success” looks like.

- What happens if weight loss slows or rebounds? Good programs plan for plateaus and chronic disease management.

Real-world experiences: what families and teens often go through (about 500+ words)

The internet loves a dramatic “before-and-after,” but real life is usually more like “before, during, after, and then… every Tuesday forever.”

Below are common experiences families and clinical teams often describeshared here as composite, illustrative scenarios, not as any one person’s story.

The first surprise is how long the decision takes. Many families expect a quick referral and a quick surgery date. Instead, they discover

a months-long process that includes nutrition visits, lab work, mental health screening, and education sessions that feel a bit like a crash course

in “How Your Body Works and Why It’s Been Mad at You.” Teens often start out thinking the program is just a gatekeeper. Later, many realize the program

is the safety net that keeps things from unraveling after surgery.

The second surprise is the “identity shift.” Some teens with severe obesity have spent years being told their body is the problem.

When surgery finally reduces hunger signals and weight begins to drop, it can be emotionally jarringrelief mixed with grief, excitement mixed with anxiety.

A teen might say, “I’m finally not hungry all the time,” and then immediately worry, “What if this stops working?” That’s why mental health support

matters before and after the procedure. The goal isn’t only weight loss; it’s helping a young person build a stable relationship with food,

their body, and their future.

School and social life can be unexpectedly complicated. Early recovery often means smaller meals, a careful eating schedule,

and lots of waternone of which blend smoothly with cafeteria chaos. Some teens don’t want classmates noticing their tiny portions; others worry

teachers will misunderstand frequent bathroom breaks or fatigue during the adjustment period. Families who plan aheadpacking appropriate snacks,

coordinating with a school nurse, and giving the teen language to explain changes without oversharingtend to feel more in control.

Then there’s the “vitamin reality check.” Plenty of teens can follow a sports training plan, but forgetful supplement use is

practically a teenage art form. Many programs coach families to treat vitamins like brushing teeth: non-negotiable, routine, and supported by reminders.

Some parents set up weekly pill organizers; some teens use phone alarms; some tie supplements to a daily habit like breakfast or bedtime.

The point is simple: the surgery can improve health, but it also makes follow-up and nutrition compliance more important than ever.

Finally, families often learn that the whole household changes. When a teen is recovering, the kitchen becomes a team sport:

protein-first meals, fewer sugary drinks, more deliberate shopping, and a new respect for sleep. Some caregivers report that the most powerful part

of the process isn’t the surgeryit’s the family building routines that were hard to build before. Others discover friction, especially if relatives

disagree about surgery or dismiss obesity as “just willpower.” Programs that offer education for caregiversand language for handling stigmacan make

the difference between a teen feeling supported or feeling judged.

In short: adolescent bariatric surgery is rarely a single event. It’s a long-term treatment pathone that can be incredibly effective when matched to

the right patient, supported by a skilled team, and backed by a family willing to do the unglamorous, everyday work that keeps results steady.

Conclusion: what this “surge” should tell us

Weight-control surgery is increasing among children and teens, and the trend reflects bigger shifts in pediatric healthcare:

severe obesity is more common, evidence has strengthened, and professional guidance now supports earlier, more intensive treatment when appropriate.

But the most important takeaway is not that “kids are getting surgery.” It’s that pediatric obesity is being treated more like the chronic disease it isusing

layered care that can include lifestyle therapy, medications, and surgery in specialized centers.

If you’re a parent reading this, remember: the right next step usually isn’t “surgery or no surgery.” It’s “get a qualified evaluation.”

The best decision is an informed oneand it should be made with a multidisciplinary pediatric team that treats your teen with dignity, not judgment.