Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First Things First: What’s a Bear Market, Anyway?

- Three Ways to Think About a Bond Bear Market

- Why Bond Prices Fall When Interest Rates Rise

- Recent History: The Bond Bear Market of the Early 2020s

- What a Bond Bear Market Means for Different Types of Investors

- How to Survive (and Even Benefit From) a Bond Bear Market

- Common Myths About Bond Bear Markets

- Real-World Lessons from a Bond Bear Market (Experience Section)

- The Bottom Line: Bond Bears, Common Sense, and Your Portfolio

If you’ve been told your “safe” bonds are suddenly in a bear market,

you might be wondering: Wait… aren’t bear markets just for stocks? And what does any of this

actually mean for my money? Take a breath. Let’s unpack what a bond bear market really is,

why it happens, and how to get through one with your sanity (and long-term plan) intact.

First Things First: What’s a Bear Market, Anyway?

The stock market version (the one everyone quotes)

In stock-land, a bear market is usually defined as a peak-to-trough drop of 20% or more

in a major index like the S&P 500. It’s a simple rule of thumb, not a law of physics, but it gives

investors a shared language for “this is bad, and not just a random wobble.”

That 20% line works reasonably well for stocks because they’re volatile. A big chunk of your return

comes from price movement, and prices can move dramatically in both directions over short periods.

Why that definition doesn’t fit bonds very well

Bonds are different. A plain vanilla U.S. Treasury bond doesn’t have earnings surprises, CEO scandals,

or meme-stock mania. It has:

- A fixed interest payment (the coupon)

- A maturity date when you get your principal back

- Price changes mainly driven by interest rates and inflation expectations

Because bonds are designed to be comparatively stable, a 20% price drop in high-quality government

bonds is historically rare. You’d need a huge, fast jump in interest rates or a long, grinding

period of inflation to get that kind of damage.

That’s why when people talk about a bond bear market, they’re often using the term

more loosely than they do for stocks. There’s no universally agreed benchmark. Instead, professionals

look at a mix of:

- Price drawdowns (how far prices fall from a previous peak)

- Real returns (after inflation)

- How long the pain lasts (years, sometimes decades in extreme cases)

Three Ways to Think About a Bond Bear Market

1. The price-drop definition

One approach is to borrow the stock rule and apply it to bond indexes. For example, if

a long-term Treasury index falls more than 20% from its high, many analysts would

comfortably call that a bond bear market.

That’s basically what happened in the early-2020s when interest rates shot higher from

near-zero levels. Long-duration bonds saw drawdowns that were, by historical standards,

unusually deep for “safe” assets.

2. The “inflation is eating my lunch” definition

A second way to define a bond bear market is in real termsthat is, after adjusting returns

for inflation. This view says:

“If my bond portfolio loses significant purchasing power over many years, I’m living

through a bond bear market, even if the nominal price drop doesn’t look that scary.”

That’s not just theory. Historically, there have been long stretches when

long-term government bonds lost a huge chunk of their value after inflation,

over decades, not months. In other words, you kept getting your coupons,

but what those dollars could buy shrank painfully over time.

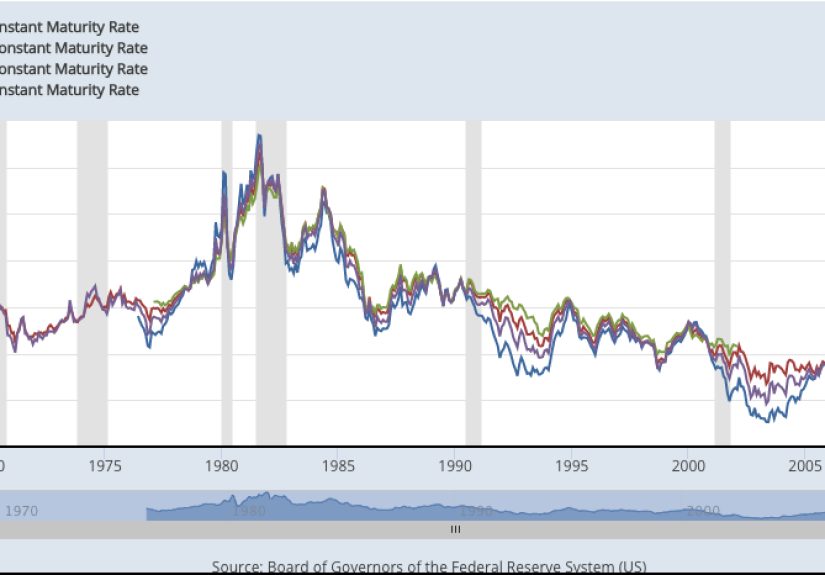

3. The “interest-rate regime shift” definition

A third way is more narrative and less numerical. In this view, a bond bear market happens

when we move from a world of:

- Falling or stable interest rates, which tend to support bond prices

- To a world of rising rates and sticky inflation, which tends to pressure bond prices

If you had a four-decade bull market in bonds built on declining interest rates, then

a prolonged period of rising or choppy rates can feel like the mirror image: a long,

grinding bond bear market in which returns are muted and volatility feels strangely high

for something that’s supposed to be the “boring” part of your portfolio.

Why Bond Prices Fall When Interest Rates Rise

Here’s the heart of the issue: bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions.

When rates go up, existing bond prices go down, and when rates go down,

existing bond prices go up. That’s the classic see-saw.

Imagine you bought a 10-year bond paying 3% interest. The next day,

new bonds come out paying 5%. No one wants your sad little 3% bond unless you

cut the price so that, from the buyer’s perspective, the overall return looks competitive

with the new 5% issue. That price cut is your temporary pain.

Duration: your one-word bond risk translator

To measure how sensitive a bond is to rate changes, professionals use

a concept called duration. It’s not just “time to maturity”; it’s a weighted measure

of all the bond’s cash flows.

Rough rule of thumb:

- A bond (or bond fund) with a duration of 5 will lose about 5% in price if interest rates jump 1 percentage point, all else equal.

- A bond with a duration of 10 could lose about 10% for the same rate move.

This is why long-term bonds were hit so hard when rates rose rapidly: their higher duration makes

them far more sensitive to interest-rate changes than shorter-term bonds.

Recent History: The Bond Bear Market of the Early 2020s

For decades, investors got used to falling and then ultra-low interest rates.

That created almost a golden age for traditional bond portfolios: you collected

income and enjoyed occasional price gains when rates fell further.

Then inflation surged. Starting in 2022, central banks, especially the U.S. Federal Reserve,

responded with aggressive rate hikes. That’s when the “safe” side of portfolios suddenly

didn’t feel so safe anymore:

- Bond indexes posted some of their worst returns in modern history, particularly in 2021–2022.

- The classic 60/40 portfolio (60% stocks, 40% bonds) suffered because both sides got hit at once.

- Long-term government bonds saw drawdowns that rivaled or exceeded many stock bear marketsespecially after inflation.

For many investors, this was their first real experience with a bond bear market. It didn’t look like

the tech wreck of 2000 or the global financial crisis of 2008, but emotionally it rhymed:

the thing that was supposed to protect you suddenly felt like a problem child.

What a Bond Bear Market Means for Different Types of Investors

If you’re still saving and far from retirement

Weirdly, a bond bear market can be good news for younger or mid-career investors. Why?

- You’re likely buying bonds or bond funds regularly inside retirement accounts.

- Lower prices and higher yields today can mean better long-term returns.

- Short-term losses are painful on paper, but you’re effectively “buying the dip” in fixed income.

In English: a bond bear market can be your friend if you’re adding new money and have

a long time horizon.

If you’re near or in retirement

For retirees, the pain feels more personal. You’re not just watching balances bounce around;

you may be withdrawing from those same assets to pay the bills. A bond bear market can:

- Temporarily reduce the value of your “safe” bucket.

- Make it riskier to sell long-duration bonds at a loss to fund near-term income.

- Raise anxiety about whether your plan still works.

The silver lining: as old bonds mature or funds rebalance, they can be reinvested at higher yields.

Over time, that extra income can help your portfolio heal and even end up in a stronger place

than if rates had stayed low.

If you love your 60/40 portfolio

The classic 60/40 portfolio had a rough period when both stocks and bonds fell together.

That doesn’t mean the idea of mixing growth assets (stocks) with stabilizers (bonds) suddenly

stopped working. It does mean:

- Correlation between stocks and bonds can spike in certain environments (inflation shocks).

- Long-term bond allocations may need to reflect your tolerance for drawdowns, not just yield hunger.

- Rebalancing during bear markets is emotionally hard but mathematically powerful.

How to Survive (and Even Benefit From) a Bond Bear Market

1. Match your bonds to your time horizon

If you need the money soon, shorter-term bonds or cash-like instruments usually make more sense

than stretching for yield in long-duration bonds. The longer the duration, the more “roller coaster”

you’re signing up for when rates move.

2. Think in real terms, not just nominal returns

A bond yielding 3% when inflation is 1% feels very different from a bond yielding 5%

when inflation is 4%. In both cases, your real return (after inflation) is roughly 2%.

In a bond bear market driven by inflation, it’s crucial to focus on purchasing power, not just coupons.

3. Consider a bond ladder or diversified bond funds

A bond ladder spreads your money across different maturities. As each rung matures,

you can reinvest at current yields. This naturally takes advantage of higher rates over time and reduces

your sensitivity to any single interest-rate move.

Well-managed bond funds and ETFs can do something similar for you under the hood,

actively adjusting duration, credit quality, and sectors.

4. Don’t let “bear market” headlines rewrite your entire plan

The phrase “bear market” is emotionally loaded. For stocks, it often comes with scary charts

and doomsday TV segments. When that language gets applied to bonds, it’s easy to panic and

abandon a sensible allocation.

But remember: a bond’s future cash flows are contractual. As long as the issuer doesn’t default,

you still get interest and principal back. Price volatility in the meantime is uncomfortable,

but it’s not the same as permanent impairment.

5. Rebalance when it feels worst

A bond bear market can leave your portfolio looking lopsided. Maybe your stocks held up relatively

better, or maybe everything fell but bonds fell “less badly” than growth stocks. Either way, periodic

rebalancingselling a bit of what did better and buying what laggedforces you to

systematically buy low and sell high.

Common Myths About Bond Bear Markets

Myth 1: “Bonds are supposed to be safe; they can’t have big losses.”

Bonds are generally safer than stocks, but “safer” is not the same as “never goes down.”

Interest-rate risk and inflation risk are real. Long-term government bonds, in particular, can see

large price declines when rates jump sharply, even if credit risk is minimal.

Myth 2: “If my bond fund is down, I should just move everything to cash.”

Moving everything to cash locks in your current yields and your current losses.

If rates later fall or stabilize, you miss the opportunity for bond prices to recover.

A better approach is usually to align your bond mix with your actual spending needs and

risk tolerance, not with last quarter’s return chart.

Myth 3: “The bond market is broken.”

It’s not broken; it’s doing exactly what it’s designed to dorepricing future cash flows to

reflect new information about inflation, growth, and central-bank policy. That repricing can be

painful if you arrived late to the party, but it also sets the stage for higher future returns

from higher starting yields.

Real-World Lessons from a Bond Bear Market (Experience Section)

Let’s strip away the jargon and talk about how a bond bear market actually feels.

Imagine an investor named Alex. For years, Alex heard the same refrain from financial gurus:

“Stocks for growth, bonds for safety.” So Alex happily stuffed the “safe” side of the portfolio with

intermediate and long-term bond funds, barely glancing at them. Stocks were the exciting part;

bonds were the quiet roommate.

Then rates started rising fast. Suddenly, Alex’s “safe” funds were the ones showing what felt like

shocking declines. The headlines screamed about the “worst bond market in decades.” Statements showed

double-digit drops in bond holdingsnumbers Alex had always mentally reserved for stocks. That

disconnect created a powerful feeling: Wait, this isn’t how it was supposed to work.

The first instinct was classic: “Should I just sell before it gets worse?” Alex called an advisor,

who did something very un-Wall-Street: they started with feelings, not formulas. They acknowledged that

it’s completely rational to feel alarmed when the “safe” side is flashing red. Then they walked through

the actual math:

- Yes, prices were down.

- But yields on new bonds were much higher than they’d been in years.

- As old bonds matured or fund managers repositioned, the portfolio would gradually lock in those higher yields.

The advisor pulled out a simple illustration: if you buy a bond fund at a yield of, say, 1.5%,

your long-term return expectations are low from day one. When yields jump to 4–5%, your short-term

statement looks ugly, but your long-term return math actually improves. The temporary pain is the price

of admission to a better yield environment.

Alex also learned how duration worked. It turned out that the bond fund with the biggest losses

also had the longest duration. The advisor suggested gradually shifting some of that exposure toward

shorter-duration funds and a bond ladder for the money Alex planned to spend in the next five to seven years.

That simple tweak reduced the emotional roller coaster without abandoning bonds entirely.

Over the next couple of years, something interesting happened. The scary headlines faded. Dividends from the

bond fundsnow at higher yieldsstarted to feel meaningful. The gap created by earlier price declines slowly

narrowed as income piled up. Alex’s reaction shifted from “My safe assets betrayed me” to “Okay, this took

a detour, but the engine is working again.”

The biggest lesson Alex took away wasn’t about predicting interest rates. It was about expectations.

Bonds are not magic shock absorbers that always go up or stay flat when stocks fall. They are

toolspowerful oneswhose behavior depends on inflation, rates, and your time horizon. If you expect

them to be perfectly smooth, every bump will feel like a crisis. If you expect them to wobble sometimes,

but to pay you steadily and help manage long-term risk, the same bump becomes just another chapter in a

long investing story.

So what does a bond bear market feel like in real life? Confusing at first, then uncomfortable, and

finallyif you stick with a sensible planstrangely educational. You learn that “safe” doesn’t mean

“never volatile,” that rising yields are both a threat and an opportunity, and that long-term investing

wisdom applies to bonds just as much as it does to stocks: diversify, match your risks to your goals,

and don’t let short-term fear hijack a long-term strategy.

The Bottom Line: Bond Bears, Common Sense, and Your Portfolio

A bond bear market isn’t just a scary phrase borrowed from the stock world. It’s a reminder that even

the safest-seeming assets live in the real world of inflation, interest rates, and investor emotions.

Sometimes that world delivers painfully negative returns, especially if you arrived late to a long bull run.

But bond bear markets also reset the playing field. Higher yields today can translate into healthier,

more durable income streams tomorrow. If you understand what drives bond prices, match your bond choices

to your time horizon, and resist the urge to react to every headline, you can move through a bond bear market

withyesa little bit of discomfort, but also with a lot of common sense.