Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Informed Consent” Means (In Plain English)

- So What’s the “Informed Consent Model” for HRT?

- How It Differs From a “Gatekeeping” or “Letter-Required” Approach

- How the Informed Consent Process Works (Step by Step)

- Step 1: Goals conversation (the “What are we trying to accomplish?” talk)

- Step 2: Medical history + risk screening

- Step 3: Education on benefits, risks, alternatives, and unknowns

- Step 4: Baseline exam and labs (when appropriate)

- Step 5: Consent documentation

- Step 6: Treatment plan + follow-up schedule

- What Clinicians Are Responsible For (And What They’re Not)

- Common Questions to Ask at an Informed Consent HRT Visit

- Special Considerations for Teens and Young Adults

- Informed Consent for Menopause HRT: What “Good” Looks Like

- What the Model Gets Right (And Where It Can Go Wrong)

- Conclusion: Informed Consent Is a Process, Not a Paper

- Real-World Experiences With the Informed Consent Model (Patient and Clinician Perspectives)

“HRT” (hormone replacement therapy) can mean different things depending on who you ask. For many people, it refers

to menopause hormone therapy (estrogen with or without progestogen). For others, it means

gender-affirming hormone therapy (often called GAHT). Either way, one phrase keeps popping up in

clinics, group chats, and search bars: the informed consent model.

If that sounds like a legal drama (“Objection! Exhibit A: this pamphlet!”), here’s the good news: informed consent

is actually a core part of everyday healthcare. The “informed consent model” for HRT simply puts that principle

front and centerso decisions happen through clear education, real conversation, and shared planning, rather than

unnecessary hoops or “prove yourself” gatekeeping.

Let’s break down what this model is, how it works in real life, what you can expect at an appointment, and what

questions to ask so you leave with confidencenot confusion and a mysterious handout you’ll never read.

What “Informed Consent” Means (In Plain English)

Informed consent is a process, not a vibe and not just a signature. It means a clinician explains:

- What the treatment is and what it’s for

- Expected benefits and realistic outcomes

- Risks and side effects (common and serious)

- Alternatives (including doing nothing yet)

- Unknowns and where evidence is still evolving

- Practical details (how it’s taken, monitoring, follow-ups, costs)

Then you get space to ask questions, consider your options, and decide freelywithout pressure. The clinician also

checks that you have decision-making capacity for the choice at hand and that the plan fits your

health history.

So What’s the “Informed Consent Model” for HRT?

In many U.S. settings, the term “informed consent model” is most often used in the context of

gender-affirming hormone therapy. Historically, some systems required a mental health professional’s

letter (or multiple letters) before a patient could start hormones. In an informed-consent approach, a qualified

medical provider can initiate HRT after a thorough education-and-consent processwithout automatically requiring a

referral letter as a gatekeeping step.

Important detail: this doesn’t mean “no assessment.” It means the assessment is focused on medical safety,

patient goals, and informed decision-makingnot on making someone “prove” their identity or meet a one-size-fits-all checklist.

For menopause hormone therapy, you may not hear clinics call it an “informed consent model,” but the

underlying approach is similar: individualized counseling, shared decision-making, and periodic re-evaluation to ensure

the benefits still outweigh the risks for your situation.

How It Differs From a “Gatekeeping” or “Letter-Required” Approach

1) Who leads the decision

Informed consent model: You and your clinician collaborate. You set goals; the clinician provides

evidence, safety screening, and guidance. The emphasis is on autonomy plus medical responsibility.

Letter-required model: A third party (often a therapist) may be positioned as the “permission slip,”

even if your medical provider is the one prescribing and monitoring treatment.

2) What gets evaluated

Informed consent model: Focuses on medical history, contraindications, risk factors, expectations,

support needs, and follow-up planning.

Gatekeeping model: Can drift toward evaluating whether a person is “really” eligiblesometimes using

narrow stereotypes that don’t reflect modern standards of care.

3) Speed and access

Informed consent model: Often reduces delays by streamlining steps that aren’t medically necessary.

That matters because long waits can increase distress and reduce continuity of care.

Reality check: Clinics still may require multiple visitsespecially if lab work, complex medical

history, or careful titration is needed. “Streamlined” doesn’t mean “rushed.”

How the Informed Consent Process Works (Step by Step)

Every clinic is a little different, but an informed-consent HRT pathway in the U.S. often looks like this:

Step 1: Goals conversation (the “What are we trying to accomplish?” talk)

Your clinician will ask what you want help with:

- For menopause: hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disruption, vaginal dryness, mood shifts, etc.

- For gender-affirming care: desired physical changes, timeline expectations, dysphoria triggers, and priorities.

This is where good care avoids assumptions. Two people can request “HRT” and mean totally different outcomes.

Step 2: Medical history + risk screening

Expect questions about:

- Personal and family history (blood clots, stroke, heart disease, certain cancers)

- Migraines, liver disease, uncontrolled high blood pressure, smoking/vaping, and other risk factors

- Current medications and supplements (interactions matter)

- Mental health history (not to “disqualify,” but to support safety and stability)

Step 3: Education on benefits, risks, alternatives, and unknowns

This is the core of informed consent. A strong clinician will cover:

- Expected changes and typical timelines (and what may not change)

- Common side effects vs. rare but serious risks

- Fertility considerations (if relevant) and preservation options

- Alternatives: non-hormonal treatments, lifestyle changes, therapy support, or watchful waiting

- Reversibility: which effects may reverse if treatment stops and which might not

A practical example: a clinician might explain that a patch, gel, or pill can differ in convenience and risk profile.

Or that dose changes are usually gradual, based on response and lab monitoringnot a “set it and forget it” situation.

Step 4: Baseline exam and labs (when appropriate)

Depending on the type of HRT and your health history, a clinician may:

- Check blood pressure, weight, and general health markers

- Order baseline labs (for example, to guide dosing or monitor safety)

- Review preventive care needs (like screenings that still apply regardless of gender identity)

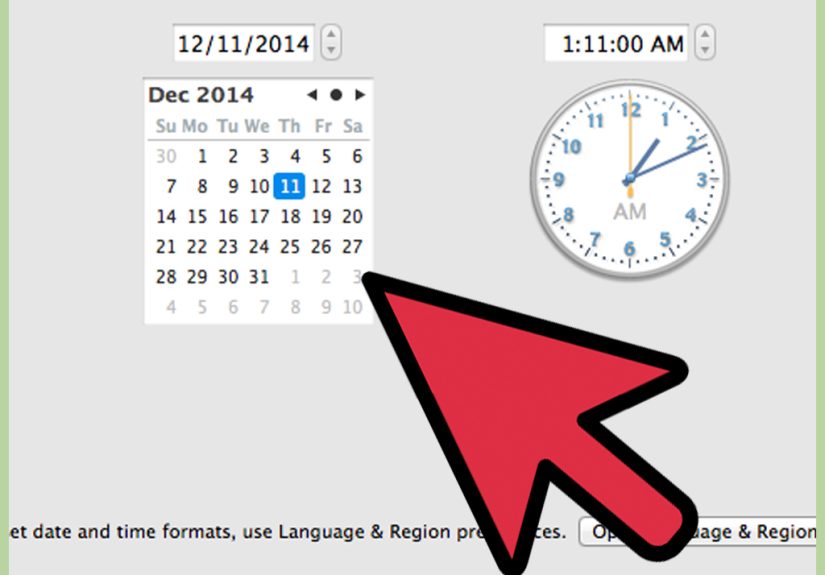

Step 5: Consent documentation

Many clinics use a written consent form summarizing risks, benefits, alternatives, and patient responsibilities.

You’ll review it together, not just sign it like you’re accepting a software update.

Step 6: Treatment plan + follow-up schedule

Informed consent includes planning for what comes next:

- When you’ll follow up (often a few weeks to months at first)

- How side effects will be handled

- What symptoms warrant urgent care

- How and when labs will be repeated (if needed)

- How dose adjustments will be decided

What Clinicians Are Responsible For (And What They’re Not)

In an informed-consent model, clinicians still have real responsibilities:

- Provide accurate, understandable information (no jargon ambushes)

- Assess decision-making capacity for this choice

- Screen for safety issues and address modifiable risks

- Recommend evidence-based dosing and monitoring

- Document the discussion

- Offer referrals when helpful (specialists, mental health support, fertility counseling)

What they’re not responsible for: acting like a bouncer outside the “HRT club” deciding who is “valid enough.”

Ethical care respects a patient’s autonomy while still practicing good medicine.

Common Questions to Ask at an Informed Consent HRT Visit

If you want to leave an appointment feeling informed (instead of just… vaguely “consented”), consider asking:

Benefits and expectations

- What changes are most likely for me, and what timeline is typical?

- Which effects may be permanent vs. reversible if I stop?

- How will we measure whether it’s helpingsymptoms, labs, both?

Risks and safety

- What risks apply most to my health history and family history?

- What warning signs should send me to urgent care?

- Do I need to change anything (like smoking) to reduce risk?

Options and logistics

- What forms are available (pill, patch, injection, topical), and why choose one?

- How often are follow-ups and labs?

- What happens if I miss a dose or want to pause treatment?

Special Considerations for Teens and Young Adults

If you’re under 18, informed consent still mattersbut legal requirements often add layers, such as parent/guardian

involvement and stricter clinic policies. Some U.S. providers have specific age thresholds, and many require

additional consent steps for minors.

If this applies to you, the safest next step is to talk with a licensed clinician who can explain what is allowed

in your state and what options are appropriate for your health and age. Please don’t self-medicate or use hormones

without medical supervisionHRT is prescription care that requires monitoring.

Informed Consent for Menopause HRT: What “Good” Looks Like

For menopause, a high-quality informed-consent conversation usually includes:

- Why you’re considering HRT (symptom relief is typically the main goal)

- Type of therapy (estrogen alone vs. estrogen + progestogen, depending on uterus status)

- Route and dose (systemic vs. local/vaginal; lowest effective dose is often discussed)

- Individual risk profile (age, time since menopause, clot/stroke risk, cancer history)

- How long to use it and the plan for reassessment

In recent U.S. news, federal labeling discussions around menopause hormone products have continued to evolve, reflecting

how risk is not “one size fits all.” The takeaway for patients is the same: informed consent should be individualized,

evidence-based, and revisited over timeespecially as health history changes.

What the Model Gets Right (And Where It Can Go Wrong)

What it gets right

- Respects autonomy: you’re the decision-maker, not a passive recipient of care.

- Improves transparency: risks and limitations are discussed up front.

- Reduces unnecessary barriers: fewer delays when a referral letter isn’t clinically needed.

- Builds trust: good consent conversations create better long-term adherence and follow-up.

Where it can go wrong

- Rushed visits: consent becomes “sign here” instead of “let’s talk.”

- Information overload: too much jargon, not enough clarity.

- Uneven standards: quality varies by clinic, state rules, and provider training.

- False expectations: “informed consent” does not mean “no monitoring” or “instant results.”

The best safeguard is simple: a clinic that treats consent as an ongoing conversation, not a one-time paperwork event.

Conclusion: Informed Consent Is a Process, Not a Paper

The informed consent model for HRT is about doing healthcare the way it should be done: with honest information,

thoughtful risk screening, respect for your goals, and a plan for safe follow-up. Whether you’re considering HRT for

menopause symptoms or gender-affirming care, the heart of the model is the sameyou deserve to understand your

options, and you deserve a voice in what happens next.

If you’re exploring HRT, aim for a provider who welcomes questions, explains tradeoffs clearly, and treats consent as

an ongoing partnership. Your body isn’t a pop-up notification. You shouldn’t have to click “Accept” without reading.

Real-World Experiences With the Informed Consent Model (Patient and Clinician Perspectives)

People often describe their first informed-consent HRT appointment as a strange mix of relief and information overload

like finally getting into a long-awaited concert and realizing you’re standing next to the speakers. The relief usually

comes from being treated like a capable human being. Instead of feeling interrogated, many patients say they feel

listened to: a clinician asks what they’re hoping will change, what they’re worried about, and what a

“good outcome” looks like in everyday life (sleeping through the night, fewer hot flashes, feeling more at home in the

mirror, or simply having their discomfort taken seriously).

Another common experience is the shift from “I need permission” to “I need a plan.” Patients often report that the best

informed-consent visits feel practical. A provider might say, “Here’s what we expect, here’s what we monitor, and here’s

how we’ll adjust if your body reacts differently than the textbook.” That kind of conversation can be especially grounding

for people who arrive anxiousbecause the internet tends to make every side effect sound like it’s either guaranteed or

apocalyptic, with no middle ground.

Many patients also appreciate that informed consent doesn’t pretend uncertainty doesn’t exist. Instead of overselling HRT

as a magic wand, clinicians in strong informed-consent programs often name the unknowns out loud: “We have good evidence

here, less evidence there, and we’ll make decisions based on both science and your response.” That honesty can build trust.

It also helps people avoid the emotional whiplash of unrealistic expectationslike assuming every symptom will vanish in a

week or every physical change will happen on a predictable schedule.

Of course, not every experience is perfect. Some people describe the downside of “efficient” clinics: the visit moves fast,

the consent form is long, and the conversation can feel like drinking from a firehose. A few patients report leaving with

a prescription but still feeling unsure about the fine printespecially around what to do if they miss doses, how soon

follow-up happens, or which warning signs are truly urgent. When that happens, it’s not a failure of the informed consent

concept; it’s a reminder that time, clarity, and teach-back (having the patient repeat the plan in their own

words) matter.

Clinicians who support the informed consent model often describe their experience in a surprisingly similar way: relief and

responsibility. The relief is being able to practice without forcing patients into unnecessary hoops. The responsibility is

making sure “informed” is realusing plain language, checking understanding, and documenting the discussion carefully. Many

providers note that the model works best when it’s paired with strong follow-up systems: easy messaging for questions, clear

lab schedules, and a culture where patients aren’t embarrassed to say, “I read the handout… and I still don’t get it.”

Finally, people commonly share that informed consent can be empowering even when they decide not to start HRT right

away. Some patients leave the visit choosing a non-hormonal option, a different route (local vs. systemic), a slower dose

ramp, or simply more time. And that’s the point: informed consent isn’t designed to push everyone toward the same choice.

It’s designed to make sure the choicewhatever it isbelongs to the patient, is medically safe, and is supported by a plan.