Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The short answer: treatment is usually needed when function is affectedor when the bend is clearly progressing

- Quick primer: what Dupuytren’s contracture actually is (and what it isn’t)

- Why many people don’t need treatment right away

- So… when exactly does Dupuytren’s cross into “needs treatment” territory?

- What happens at the doctor’s office: how treatment decisions are made

- Treatment options (from least invasive to most invasive)

- 1) Observation and symptom management (when bending is minimal)

- 2) Steroid injections for painful nodules (selected situations)

- 3) Collagenase injection (enzymatic “cord dissolver”) for a palpable cord

- 4) Needle aponeurotomy (needle fasciotomy): “divide the cord with a needle”

- 5) Surgery (fasciectomy / dermofasciectomy): more invasive, often more durable

- 6) Radiation therapy (early disease, specialized use)

- How to pick a treatment: a practical decision framework

- What to expect after treatment (and why rehab matters)

- When you should get evaluated sooner rather than later

- FAQ: quick, honest answers

- Real-world experiences: what people commonly notice when Dupuytren’s starts “needing treatment” (about )

- Conclusion

Dupuytren’s contracture is the ultimate slow-burn: your hand feels mostly fine… until you realize your ring finger has been quietly “moving in” toward your palm like it pays rent there. The tricky part isn’t spotting it (hello, palm lump and tight cord). The tricky part is knowing when it actually needs treatmentbecause not everyone with Dupuytren’s needs a procedure, and jumping in too early can be like fixing a squeaky door by replacing the entire house.

This guide breaks down the practical “treatment line” in plain English: the signs and measurements clinicians use, the daily-life red flags that matter more than any single number, and how to choose between options like injections, needle procedures, and surgery. We’ll keep it honest, specific, and (as much as a hand condition allows) pretty fun.

The short answer: treatment is usually needed when function is affectedor when the bend is clearly progressing

Most specialists don’t treat Dupuytren’s just because a lump exists. Treatment is typically considered when:

- Your hand can’t do what you need it to do (work tasks, hobbies, self-care, gripping, typing, gloves, pockets, etc.).

- You can’t lay your hand flat on a table (a classic “tabletop test” fail).

- The contracture reaches common treatment thresholdsoften around 30° at the MCP joint (the knuckle where the finger meets the hand) or 15–20° at the PIP joint (the middle finger joint). Some clinicians consider any meaningful PIP contracture worth a hand-surgery evaluation because PIP joints can become stubborn over time.

- The bend is progressing (faster change, new cords, worsening straightening) even if daily function hasn’t fully cratered yet.

- Skin problems develop (deep creases, pitting, cracking) or the cord is pulling enough to cause irritation and hygiene issues.

Bottom line: Dupuytren’s needs treatment when it starts to cost you function, comfort, or options. Early intervention can sometimes be easierespecially before joints stiffenbut “early” doesn’t mean “the moment you notice a bump.”

Quick primer: what Dupuytren’s contracture actually is (and what it isn’t)

Dupuytren’s contracture happens when tissue in the palm (the palmar fascia) thickens and tightens over time. It can form:

- Nodules: firm lumps in the palm (often near the ring or small finger side).

- Cords: rope-like bands under the skin that can pull fingers into a bent position.

- Contracture: the finger can’t fully straighten, even if you try.

It’s not the same thing as arthritis (joint wear-and-tear), trigger finger (tendon catching), or “I used my hands too much.” It tends to be influenced by genetics and becomes more common with age. Some people have a mild, slow course. Others progress more quickly or develop more severe bending.

Why many people don’t need treatment right away

Here’s the inconvenient truth: there’s no permanent cure for Dupuytren’s contracture. Most treatments can straighten the finger, but the condition can return over time. That’s why “watchful waiting” is common when the disease is mild.

If you have nodules without meaningful bendingor a very small bend that doesn’t affect functionyour clinician may recommend:

- Monitoring (photos, periodic measurements, tracking changes).

- Protecting the skin (moisturizing, treating cracks, avoiding irritation).

- Addressing comfort if a nodule is sore (sometimes clinicians discuss steroid injections for painful nodules, though that’s not a “contracture fix”).

Also, some early lumps never become a major contracture. Treating too early can expose you to risks and recovery time before there’s a clear payoff.

So… when exactly does Dupuytren’s cross into “needs treatment” territory?

Think of it like a three-part decision: function, finger angle, and trajectory.

1) Function: the “real life” test that counts

Even a modest bend can matter if you use your hands in specific ways (musicians, mechanics, healthcare workers, hairstylists, athletes, gamers, artists, cooksbasically anyone with a pulse). Common function-based reasons people seek treatment include:

- Difficulty putting your hand in a pocket (the finger catches).

- Trouble wearing gloves (fingers don’t slide in easily).

- Problems with typing or using a keyboard (especially the small finger “reach”).

- Grip and grasp issues (holding tools, opening jars, lifting weights, carrying bags).

- Hygiene and self-care issues (washing your face, putting on makeup, combing hair, fastening buttons).

- Safety/work limitations (getting a hand flat on a surface, stabilizing objects, wearing protective equipment).

If you’re changing how you do daily tasksor avoiding themDupuytren’s is no longer a harmless houseguest. That’s often the moment treatment becomes worth discussing.

2) The tabletop test: a low-tech clue with high value

The tabletop test is simple: place your hand palm-down on a flat surface. If you can’t get your palm and fingers flat (because one or more fingers won’t straighten), that’s a classic sign the contracture is meaningful. It’s not the only test, but it often correlates with “this is starting to matter.”

3) Angle thresholds: the numbers clinicians use as guideposts

Clinicians often measure contracture with a goniometer (a tool for joint angles). While exact thresholds vary, common guideposts for considering intervention include:

- MCP joint contracture around 30° or more (the knuckle at the base of the finger).

- PIP joint contracture around 15–20° or more (the middle joint).

Why do these numbers show up so often? Because they tend to mark the point where function is more likely to be affected and where the bend may become harder to reverseespecially at the PIP joint. PIP contractures can be more resistant and more likely to leave stiffness if they’ve been present for a long time.

Important nuance: the number alone isn’t everything. A 25° contracture might be a big deal to a guitarist; a 35° contracture might bother someone lessuntil it suddenly does. The best threshold is the one that matches your actual life.

4) Trajectory: “Is this getting worse, and how fast?”

Some Dupuytren’s stays stable for years. Some progresses over months. Signs of meaningful progression include:

- New cords appearing or thickening quickly

- Increasing difficulty straightening the finger week-to-week or month-to-month

- Contracture spreading to additional fingers

- Increasing skin tightness, deepening creases, or pitting

If progression is clear, discussing treatment earlier can preserve optionsespecially if you’re trying to avoid more invasive procedures later.

What happens at the doctor’s office: how treatment decisions are made

A good evaluation usually includes:

- History: what tasks are difficult, how long symptoms have been present, and how fast things have changed.

- Exam: checking nodules, cords, skin changes, and which fingers/joints are involved.

- Measurements: angles at the MCP and PIP joints; sometimes “active extension deficit” (how far from straight you can get).

- Function goals: your job, hobbies, tolerance for downtime, and preference for minimally invasive vs. “do it once, do it bigger” surgery.

Imaging (like X-rays) usually isn’t the star of the show unless another condition is suspected. This is mostly a hands-on diagnosis with hands-on planning.

Treatment options (from least invasive to most invasive)

Once treatment is on the table (pun fully intended), your options typically fall into a few categories. The best choice depends on which joint is involved, how severe the bend is, how fast you need recovery, and your risk tolerance for recurrence.

1) Observation and symptom management (when bending is minimal)

If you still have good function and mild contracture, monitoring is often reasonable. You might track changes using periodic photos, tabletop checks, or clinician measurements. Some people also use hand therapy for comfort and to optimize motion, but therapy alone generally doesn’t “un-cord” Dupuytren’s.

2) Steroid injections for painful nodules (selected situations)

If a nodule is tender or inflamed, clinicians sometimes discuss corticosteroid injections to reduce pain and possibly soften the nodule. This is not the go-to solution for established cords causing contracturebut it can be part of comfort-focused care in early disease.

3) Collagenase injection (enzymatic “cord dissolver”) for a palpable cord

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum (commonly known by a brand name many people recognize) is an office-based procedure for adults with a palpable cord. The enzyme is injected into the cord, and the finger is later manipulated to help break the cord so the finger can straighten.

Why people like it: no big incision, typically faster recovery than open surgery, and it can be done in an outpatient setting.

Tradeoffs: bruising and swelling are common; skin tears can happen; and recurrence can still occur over time. Like all treatments, it’s a “manage and restore motion” approach, not a permanent cure.

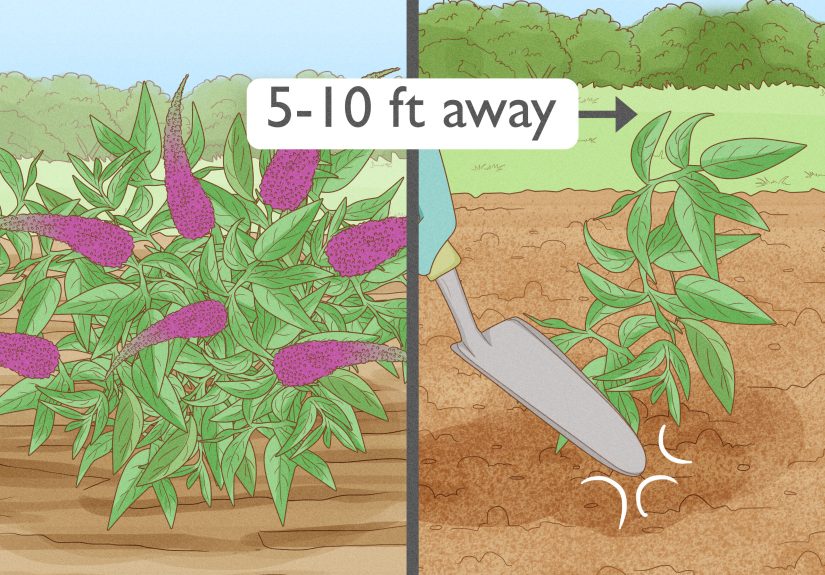

4) Needle aponeurotomy (needle fasciotomy): “divide the cord with a needle”

This minimally invasive approach uses a small needle (after numbing) to weaken or divide the cord through the skin. The finger is then straightened.

Why people like it: quick procedure, minimal downtime, often rapid improvement.

Tradeoffs: recurrence is common over time, especially compared with more extensive surgical approaches. It may be best suited to certain patterns of disease and certain joint involvement.

5) Surgery (fasciectomy / dermofasciectomy): more invasive, often more durable

Surgery is often considered when contracture is more severe, when the PIP joint is significantly involved, when there’s complex disease, or when minimally invasive approaches aren’t a good fit (or have already failed).

Common surgical categories include:

- Limited fasciectomy: removing the diseased fascia/cords through an incision to straighten the finger.

- Dermofasciectomy: removing the diseased tissue and involved skin; sometimes requires a skin graft. This may be considered in more aggressive or recurrent cases.

Why people choose surgery: it may provide a more substantial correction in certain cases and can be a better option for advanced or complex contractures.

Tradeoffs: longer recovery, wound care, and therapy are more common; risks can include stiffness, nerve or vessel injury, infection, and scar sensitivity. Still, for the right patient, it can be a very effective reset.

6) Radiation therapy (early disease, specialized use)

In some settings, radiation therapy is discussed for early-stage disease (before major contracture), aiming to slow progression of nodules/cord development. It’s not universal, and availability and recommendations vary. If you’re considering it, it’s worth consulting a hand specialist familiar with the evidence and local practice patterns.

How to pick a treatment: a practical decision framework

If treatment is on the table, consider these factors:

Which joint is involved: MCP vs. PIP

- MCP joint contractures often respond well to multiple approaches, including minimally invasive options.

- PIP joint contractures can be more stubborn and may be more prone to residual stiffness, especially if long-standing. The more severe and longer-lasting the PIP bend, the harder it may be to fully restore motion.

How important is quick recovery?

If you need to minimize downtime (work, caregiving, life logistics), minimally invasive options may be appealing. If you can tolerate a longer recovery for potentially longer-lasting correction, surgery might make sensedepending on severity and anatomy.

How do you feel about recurrence and repeat procedures?

Some people prefer a less invasive approach, fully aware they might need repeat treatment later. Others prefer a more extensive correction upfront. Neither approach is “more correct”it’s a values-and-lifestyle decision.

Access, cost, and clinician expertise

Not every clinic offers every procedure. Experience matters. A hand specialist can help you weigh which option fits your specific cord pattern and joint involvement.

What to expect after treatment (and why rehab matters)

Regardless of the procedure, aftercare often includes some combination of:

- Hand therapy to restore range of motion, manage swelling, and rebuild function.

- Night splinting for a period of time (varies by clinician and procedure).

- Activity modification while tissues heal.

And yes, Dupuytren’s can return. Think of treatment like straightening a bent tree branch: you can restore position, but the tree’s “growth pattern” may still be there. Monitoring and early action on recurrence can sometimes keep problems smaller.

When you should get evaluated sooner rather than later

Consider a hand specialist evaluation if:

- You fail the tabletop test (you can’t get the hand flat).

- You notice measurable progression over months.

- You have a PIP joint bend developing (middle joint contracture).

- You’re losing function at work or in daily life.

- You’re developing skin breakdown, hygiene issues, or increasing discomfort.

Even if you’re not ready to treat, a baseline exam and measurements can be incredibly usefulbecause guessing angles with the human eyeball is… an adventurous strategy.

FAQ: quick, honest answers

Is Dupuytren’s dangerous?

It’s usually not dangerous in the “life-threatening” sense. The main issue is loss of function and quality of life.

Does stretching or massage stop it?

Stretching may help comfort and general hand mobility, but it typically doesn’t stop the underlying cord formation. If a cord is pulling your finger down, you usually need a procedure to release or disrupt it.

If it doesn’t hurt, can I ignore it?

Pain isn’t the main driver. Many cords aren’t painful. The key question is function and progression.

Should I wait until it’s “really bad” before treating?

Not necessarily. Waiting can allow joints (especially PIP joints) to stiffen. A common strategy is: monitor early disease, treat when function declines or thresholds are reached, and avoid waiting until correction becomes harder.

Real-world experiences: what people commonly notice when Dupuytren’s starts “needing treatment” (about )

Note: The examples below are composites based on commonly reported patient experiences and typical clinical scenariosnot stories from any single identifiable person.

Experience #1: “It wasn’t bad… until it was.”

A lot of people describe Dupuytren’s as a condition that stays politely in the background for a while. One day there’s a small lump. Months (or years) later, there’s a thin cord you can feel when you press into the palm. At first, the finger still straightens enough that life goes on. Then a tiny moment flips the switch: your finger snags on a pocket, catches on a glove, or makes a handshake feel awkward. That’s often when someone realizes the real problem isn’t the lumpit’s that the hand is starting to change how it interacts with the world.

Experience #2: The “tabletop surprise.”

Many people don’t notice a contracture gradually worsening because it’s happening millimeter by millimeter. A classic wake-up moment is trying the tabletop test “just to see” and realizing the palm can’t go flat anymore. That’s when the bend becomes less theoretical and more measurable. People often report a mix of reactions: relief (“Okay, I’m not imagining it”), frustration (“Why does my hand have opinions?”), and urgency (“If it’s this noticeable now, what happens next?”). Clinically, this is also a useful moment because it often correlates with the stage where treatment options become more relevant.

Experience #3: Work and hobbies draw the line.

Someone who types all day may notice that the pinky’s reach is off and the hand feels clumsy on a keyboard. A musician may struggle with finger placement or clean extensions. A mechanic may find it harder to get a hand flat under a tight space or maintain certain grips. People often say, “It’s not that I can’t do itI just have to do it differently.” That “doing it differently” is frequently the first functional sign that the condition has crossed into treatment territory, even if the angles aren’t dramatic yet.

Experience #4: Choosing a treatment can feel like choosing a philosophy.

Many patients wrestle with the same decision: go minimally invasive now (with the knowledge it may return), or choose surgery for a potentially bigger, longer-lasting correction (with more recovery). People who choose a needle procedure or enzyme injection often value speed and lower invasiveness: “I want my hand back fast.” People who choose surgery often value a more thorough reset: “I’m okay investing recovery time if it helps me longer.” The most satisfied patients are usually the ones whose choice matches their actual prioritiesjob demands, caregiving responsibilities, tolerance for downtime, and how strongly they want to avoid repeat procedures.

Experience #5: The best time to treat is often “before you’re stuck.”

A common lesson is that waiting for a severe bend can make recovery harderespecially for middle-joint (PIP) contractures, which can become rigid. People who treat earlier (once function is clearly affected) often report feeling like they “caught it at the right time”: the finger straightens more easily, therapy feels more productive, and the hand returns to useful motion faster. People who wait longer can still improve, but may notice more stiffness and a longer road back.

The takeaway: In real life, the “need treatment” moment is usually when you start negotiating with your own handchanging how you grip, type, reach, wash, dress, or work. That’s the condition doing what it does. And that’s the moment to talk with a hand specialist about your options.

Conclusion

Dupuytren’s contracture doesn’t demand treatment the moment it appears. It usually needs treatment when the contracture affects function, fails the tabletop test, reaches common angle thresholds (often around 30° at the MCP joint or 15–20° at the PIP joint), or is clearly progressing. The best plan is individualizedbecause a “small” contracture can be huge for certain hands and certain lives.

If you suspect you’re crossing that line, a hand specialist can measure your angles, confirm how involved each joint is, and help you choose between minimally invasive options and surgery based on your goals. You don’t need to panicbut you also don’t need to wait until your hand feels like it’s permanently stuck in “holding an invisible TV remote” position.